The night my daughter finally saw who her husband really was, it wasn’t in a courtroom or at a lawyer’s office. It was in a crowded coffee shop on the corner of Fifth and Grant, with bad jazz leaking from tinny speakers and a crooked little American flag magnet stuck to the metal frame of the glass door. The kind of place where people sit with laptops and refill the same cup of coffee until the barista starts stacking chairs. Outside, a beat-up sedan I’d come to recognize was parked crooked across two spaces. Inside, Michael sat at one table and Emily at another, with a young woman between them like a human shield. When he grabbed my daughter’s wrist and hissed that she would “regret” walking away from him, the whole room seemed to hold its breath. That was the moment I knew I’d been right the night he put a plastic plate of scraps on the floor like I was a house pet. That was the moment every dollar, every document, every sleepless night suddenly felt worth it, because my daughter finally reached for me instead of for him.

But to understand how we got to that flag-magnet coffee shop, you have to start with Thanksgiving and a cheap white plate with a flimsy rim.

Thanksgiving in our neighborhood always looked like something out of an old postcard. Little flags on porches, inflatable turkeys bobbing sadly in patchy front yards, the smell of roasted meat drifting from kitchen windows. It was cold enough that you could see your breath, but not so cold that people stayed inside if they didn’t have to. Somewhere down the street, someone was playing Sinatra too loud, “Fly Me to the Moon” wobbling out of a Bluetooth speaker as kids tossed a football under a bare maple tree.

In my driveway, there were three unfamiliar cars.

A black SUV with temporary tags.

A low, silver sedan with dark-tinted windows.

A compact hybrid with a college parking decal in the rear windshield.

They were parked at careless angles, metal at odd diagonals across the concrete I’d poured myself three decades ago. Whoever drove them hadn’t planned for anyone else to need the driveway. Whoever drove them hadn’t been thinking about me.

I checked my watch. Five o’clock on the dot.

The invitation was still on my fridge back at the apartment, held in place with a magnet shaped like a tiny American flag. Emily had texted it and then printed a proper card too, all in the spirit of “doing things right this year.”

Thanksgiving at our place, Dad. Dinner at 5:00. Can’t wait. Love you.

I stood at the bottom of the short walkway and looked up at the house. The siding needed repainting, but the porch light I’d wired myself was warm and yellow against the November gray. Through the front window I could see movement—shadows, the flash of glassware, the slow bob of someone’s head as they laughed. Light from the chandelier I’d installed over the dining table spilled down in a soft glow.

It had been my house for thirty years. I’d built it half the time with my own calloused hands and half the time with checks written on early mornings over diner coffee. Every board, every railing, every carefully laid plank of hardwood floor had a memory stamped into it. Sarah’s laughter at the mess. Emily’s school projects spread across the table. Paint samples lined in neat rows when we argued about which shade of blue counted as “calm” and which looked like a hospital wall.

I’d thought, naively, that when Emily said “our place” in that text, she still meant this was mine too.

I walked up the path and knocked.

Laughter. Voices. The clink of silverware against plates. But no footsteps.

I waited. Knocked again, louder this time.

The door opened so suddenly I almost took a step back. Michael filled the doorway in a way that made it feel like he was blocking a goal line instead of greeting family. He was over six feet tall and broad through the shoulders, wearing an expensive-looking sweater in some muted color you only see in catalogs. He smelled like some cologne that came in a heavy bottle and cost more than my entire outfit.

He looked at me and didn’t smile.

“You’re late,” he said.

I lifted my wrist and tilted the face of my watch toward him. The watch had been a gift from Sarah for our twentieth anniversary, a simple silver thing that had outlived her and almost every piece of clothing I’d ever owned.

“Actually, I’m right on time,” I said. “Emily said five.”

He glanced over his shoulder toward the dining room, then back at me. His eyes did this little flicker thing I’d come to know too well in the years since Emily married him, like there was a calculator behind his forehead running scenarios and choosing whichever one benefited him most.

“We’re in the middle of dinner,” he said finally.

“The invitation said five,” I repeated. “It is five.”

He exhaled through his nose like this was all some big inconvenience.

Finally, he stepped aside—not the way you move to welcome someone in, but the way you shift to avoid bumping into a trash can someone left in the doorway.

I stepped past him into the foyer and stopped.

The dining room was full.

Eight, maybe nine people sat around the big table I’d stripped and re-stained just last spring. Young adults, late twenties to mid-thirties, dressed in what I think they call “smart casual” now. One guy had a beard so meticulously trimmed it looked like it had its own calendar. Another wore a shirt with tiny embroidered logos I recognized from department store ads but never from my closet. The women had that effortless, messy hair that takes two hours to do and a product budget I couldn’t begin to guess at.

Wine glasses glinted in their hands under the chandelier I’d installed myself. The table was set beautifully—cloth napkins, real plates, polished silverware. In the center, a turkey sat perfectly browned, surrounded by bowls of mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, green bean casserole, cranberry sauce, rolls in a basket with a cloth draped over them like a little curtain.

Every chair around that table was taken.

Emily came out of the kitchen carrying a big ceramic bowl. Steam rose and fogged the air for a second around her face. She was thirty-five and still had her mother’s cheekbones and her mother’s way of moving like she was consciously trying not to break anything in a world that had already broken her once.

For a second—as short and sharp as a match being struck—I saw her the way I always had, as a little girl with paint on her hands and a grin too wide for her face.

Then she saw me.

And her eyes darted away so fast you’d have missed it if you weren’t looking for it.

“Happy Thanksgiving, honey,” I said.

It came out gentle out of habit, but there was an edge behind it, a question I hadn’t let myself ask yet.

“Hi, Dad,” she said.

Her voice barely reached across the room. She shifted the bowl in her hands but didn’t move toward me. Her knuckles whitened around the ceramic edges.

Michael brushed past me, shoulder clipping mine in a way that wasn’t quite an accident.

“We’re about to eat,” he said, loud enough for his friends to hear. “You really did pick the most awkward time to show up.”

“The card said five,” I said, keeping my voice level. “It is five.”

One of his friends, the guy with the beard, raised his wine glass slightly in my direction in what might have been a half-hearted toast or a mocking salute. The woman beside him leaned close and whispered something. They both smirked.

The edges of my vision narrowed for a second. I counted chairs without meaning to.

Eight around the sides, one at the head where Michael was clearly meant to sit. All of them full. Not an inch of wood left for a man who’d signed every mortgage, hammered half the nails, and refinished that very table until his back screamed for mercy.

“Where should I sit?” I asked, and the question fell into the room like something heavy.

Michael tilted his head, pretending to study the table setup like this was some puzzling seating arrangement no one could have foreseen.

“That’s a good question,” he said.

Someone at the table let out a nervous laugh that died halfway out of their throat.

“We could squeeze in another chair,” said a woman in a red sweater, trying to be kind. “I can move down.”

“Not necessary,” Michael said.

His voice had changed. There was a note of satisfaction in it, the smug tone of someone about to land a punchline he thought was clever.

“I’ve got the perfect spot.”

He turned and walked briskly into the kitchen. I heard cabinet doors opening, something plasticky scraping, a drawer opening and closing. Emily stood completely still by the table, still gripping the bowl so tight her fingers must have ached. She was staring at a point slightly above everyone’s heads, like if she focused hard enough she could ignore what was about to happen.

Our eyes met, just for a heartbeat.

She dropped her gaze almost immediately.

Michael came back with a flimsy white plastic plate in his hand, the kind you buy in stacks of fifty at the supermarket for summer barbecues where no one remembers to recycle. The rim was too thin, already bowing slightly under its own weight.

He walked right past all those strangers at my table, right past Emily, and into the foyer.

He bent down and placed the plate on the hardwood floor a few feet from the front door.

On the floor I’d sanded and stained and sealed while Sinatra played from a small radio in the corner and Sarah complained that I was tracking sawdust into the kitchen.

Then he walked back to the table, lifted the serving fork from the turkey platter, and started scraping.

Dry bits of breast meat, half-congealed gravy, an edge of stuffing that had gone cold. He dropped them onto the plate like he was filling a dog bowl. The sound of food hitting the plastic was louder than it had any right to be.

He added a spoonful of sweet potatoes that had already formed that faint skin on top, a lump of mashed potatoes with no gravy, two green beans stuck together with cold sauce. Every motion was deliberate, theatrical.

Then he straightened, wiped his hands on a cloth napkin, and smiled.

“Right here works for you,” he said, gesturing to the plate on the floor.

No one moved.

Someone’s breathing near the end of the table got loud enough to hear. A fork slipped from a hand and clinked against a plate. The bearded friend let out a short, startled chuckle that turned into a cough when Michael shot him a look.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

Even to my own ears, my voice sounded calmer than I felt.

“Giving you exactly what you deserve,” he said. He crossed his arms, looming slightly. “You always said you weren’t picky.”

I looked at Emily.

She was staring at her own plate now, jaw tight, shoulders rigid under her sweater. The bowl she’d carried in was on the table at last, forgotten. Her fingers pressed so hard into the tablecloth I could see the tendons standing out white under her skin.

She knew. She’d known this was coming. She had not stopped it. She had not said a word.

That silence cut deeper than any of his theatrics.

I looked down at the plastic plate sitting on my beautiful hardwood floor. It was placed in the exact spot where, years earlier, Sarah had stood icing cookies with Emily while they laughed about something silly. It was positioned exactly where a dog bowl would go if I’d ever had a dog.

The furnace kicked on in the basement with a familiar thump. The refrigerator hummed in the kitchen. The house, my house, made the same comforting sounds it always had, while I stood in the middle of a scene I never could have imagined taking place under my roof.

The old Arthur would have laughed it off. He would have picked up the plate, made some self-deprecating joke about “old guys being happy anywhere,” and maybe taken it out to his truck with a little flourish, letting everyone get back to their good time. He would have told himself it wasn’t worth making a fuss. He would have swallowed the humiliation whole and washed it down with cheap beer, then lain awake that night staring at the ceiling, hearing that plastic plate every time it shifted.

But something in me, something that had been soft for too long, had hardened.

I looked at Emily one last time. She still wouldn’t look at me.

I turned, walked to the front door, opened it, and stepped out into the cold November air.

I didn’t slam it. I didn’t say anything dramatic. I didn’t pick up the plate. I just left.

As the door clicked shut behind me, the silence inside broke like a bubble. Laughter started up again, loud and a little too high. Someone poured wine. A voice said, “Well, that was awkward,” and another voice said, “He’ll be fine.”

I stood on the porch for a second, feeling the chill creep through my sweater. The porch light glowed against the dusk. An American flag I’d never taken down after summer hung limp from its bracket, edges starting to fray.

My keys weighed heavy in my pocket. The keys to this house. The keys to the property deed filed in my name at the county office. The keys to a front door I’d just been politely shown did not belong to me anymore.

I walked down the steps, got into my truck, and sat with my hands on the steering wheel, not starting the engine right away. Through the front window, I could see the shadows of people moving, someone raising a glass, Emily’s outline moving from kitchen to table.

Then I turned the key and drove away.

By the time I pulled into the parking lot of my small apartment complex—a squat, aging building with a cracked sidewalk and a decent view of the highway—I knew I wasn’t just leaving a dinner.

I was walking away from a role I’d played for far too long: the man who would swallow anything to keep a fantasy of “family” alive.

I walked into my apartment still wearing my good shoes and the sweater Emily had given me two Christmases ago. I set my keys on the little ceramic tray by the door, the one Sarah had picked up at a craft fair years before, and saw the grocery bag I’d dropped on the counter earlier—rotisserie chicken, pre-made mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, a pumpkin pie in a plastic dome. The backup dinner in case something went wrong with the main plan, because even then some part of me hadn’t trusted the evening.

I stared at the bag for a long moment. Then I moved to the small table, pulled out the chair, and sat.

What I was really looking at wasn’t the plastic containers or the faint scratches on the table’s surface.

I was staring at a flimsy white plate on a hardwood floor and hearing a man who’d eaten my food, lived in my house, spent my money, tell me I was exactly where I belonged.

The thing about men my age is people assume we’re slow. Slow to anger, slow to change, slow to learn anything new. That night, my hands found the laptop on the table faster than they had in years.

I opened my banking app.

Four years of statements lay there in neat rows, numbers marching like ants across the screen. Deposits from Evans Construction, my company. Social Security. The little bit of insurance money from Sarah’s policy. Withdrawals for groceries, utilities, truck payments.

And transfers. Lots of transfers.

Rent they never paid, because “family doesn’t charge family.” Utility bills I covered, because “we’re still trying to get back on our feet.” Checks written to “cash” and “Michael Leonardo” and “Emily Evans” for “emergencies” and “just until next month, Dad.”

I picked up a yellow legal pad and started adding.

The house would easily rent for fifteen hundred dollars a month if I listed it on the market. I knew, because I’d checked when I first bought it as a rental property years ago before letting Emily and Michael move in “temporarily.”

Four years.

Forty-eight months.

Seventy-two thousand dollars in rent that never came.

Eighty thousand dollars for LT Digital Solutions, the “can’t miss” tech startup Michael had pitched at my kitchen table two years prior, complete with jargon-laced slides and charts printed in color. I’d written a check for $80,000 and watched him sign a promissory note with his neat, practiced signature on the same evening. That note lived in my filing cabinet, because I was old-fashioned enough to still believe in paper.

Then there were the smaller amounts, the “emergencies” that had a way of showing up every time they got a new television or went on what Emily called “a much-needed weekend away.”

Two thousand for a car repair.

Three thousand for a credit card bill that “spiraled this month.”

Seven hundred and fifty when their dog—before they rehomed it for being “too much work”—needed a surgery.

Here and there, here and there, here and there, until the numbers blurred.

I didn’t need to write every line. I knew the shape of it.

Seventy-two thousand in free rent.

Eighty thousand in a loan.

Another fifteen thousand, conservatively, in assorted rescues.

One hundred sixty-seven thousand dollars.

I stared at the total on the pad for a long time. It felt wrong on some level, like a number that big shouldn’t be connected to the same word I used for folding laundry and babysitting the dog.

Family.

I thought about rounding down, the way I had rounded down everything for years, telling myself I was “overreacting” or “misunderstanding.” Instead, for the first time in a very long time, I rounded up.

“Call it $175,000,” I said aloud to the empty apartment.

One hundred seventy-five thousand dollars to end up eating from the floor.

On the top of the page, under the number, I wrote three words.

Plate on floor.

That was the debt they didn’t know they’d just taken on.

That was the promise.

I got up, walked to the metal filing cabinet against the wall, and pulled the drawer open with more force than necessary.

My handwriting stared back at me from a row of manila tabs. “Insurance – Sarah.” “Evans Construction – Taxes.” “Rental Property – Maple Street.” “Michael – Business.”

I pulled out the folder with his name and set it on the table. The promissory note was right where it belonged—crisp, white paper, clear printed text. My signature on one line, his on the other. Witness signature from a notary on Maple Avenue we’d stopped at on the way home from dinner that night.

He’d insisted we go somewhere fancy to celebrate the investment. I’d insisted we swing by a notary first.

That compromise had never looked smarter.

I went back to the cabinet and grabbed the rental property folder. The deed to the house they were living in—my house—was there. Single owner: Arthur Evans. Taxes paid. No judgment liens. No secondary mortgages.

No mention of Michael.

No mention of Emily.

No way to pretend they had any legal claim to the property.

It was all there in black and white. My generosity hadn’t left as much of a paper trail as I wished it had, but the basics—the bones—were solid.

I spread the documents out on the table and sat down again.

For a long time all I could hear was the faint hum of the refrigerator and the muffled whoosh of cars on the highway beyond my window. I thought about Sarah, about every time she’d warned me gently that giving Emily money was different than supporting her. I thought about all the times I’d said things like, “What am I supposed to do? Turn my own daughter away?”

I thought about how Sarah would have reacted to a plate on the floor.

I didn’t think she would’ve been as calm as I’d been.

My phone buzzed beside the laptop. Emily’s name lit up the screen.

I watched it ring until it went to voicemail. The notification popped up. I turned the screen face down.

If she wanted to talk, there would be time. I’d given her four years of time. I could give myself one night.

I opened a browser window and typed “state eviction law no lease” into the search bar. Links popped up with words I’d never needed to understand before: “tenancy at will,” “notice to vacate,” “justice court,” “statute of limitations.”

I read until the words blurred, then poured coffee, then read again. I took notes in my uneven block handwriting, underlining dates and requirements.

Thirty days’ written notice.

Certified mail.

If they fail to vacate, file an eviction suit.

I flipped to a fresh page and wrote another word in capital letters.

ENOUGH.

The night ticked past in a rhythm of coffee refills and legal definitions. Dawn eventually pushed pale light through the cheap blinds over my window, striping the room in gray and white. The caffeine left my hands only slightly shaky, but my thoughts were clearer than they’d been in years.

By six in the morning, I’d showered, shaved, and put on pressed khaki pants and a button-down shirt I saved for client meetings. I looked at myself in the bathroom mirror. The man staring back looked older than the sixty-three on his driver’s license. Grief etches lines you don’t see until the light hits just right.

But there was something new in his eyes. Not anger. Not exactly.

Resolve.

At six fifteen, I picked up my phone and scrolled to a name I hadn’t used in more than a year.

“Mark Vance,” a sleep-rough voice answered on the third ring.

“Mark, it’s Arthur Evans,” I said. “I need an emergency meeting.”

There was a pause. Papers rustled.

“Arthur, it’s the day after Thanksgiving,” he said.

“I know what day it is,” I said quietly.

He must’ve heard something in my tone because his voice shifted.

“Come in at nine,” he said. “Bring any documents you have. I’ll make coffee.”

By nine, I was sitting in a chair across from his desk, the promissory note, the deed, and a stack of bank printouts between us. His office smelled like printer toner, dark roast coffee, and the faint lemon of cleaning spray.

Mark was in his mid-fifties, a little paunchy around the middle, his gray hair combed into a flat line. He wore reading glasses on a chain like a librarian in an old movie but had the eyes of a man who missed nothing.

He slid the deed closer, scanned it, and nodded.

“Sole owner, that’s good,” he said. “Well, not for them. You know what I mean.”

He picked up the promissory note and read through, lips moving slightly.

“Signed, notarized, dated,” he said. “Even has a payment schedule laid out they never followed. You did this right, Arthur.”

“I did everything except say no,” I said.

He looked up at me.

“What happened?” he asked.

“My son-in-law put leftovers on a plastic plate on the floor and told me that was where I belonged,” I said bluntly. “In my own house. My daughter watched. She didn’t say a word.”

He stared at me for a second, probably weighing whether to ask if I was exaggerating.

“I wish that was the worst of it,” I added.

He leaned back slowly in his chair.

“You want to evict them,” he said.

“I want my house back,” I said. “And I want my money back. Or as much of it as the law says I can ask for.”

“All right,” he said. “Here’s the deal. Under our state law, with no written lease and no rent paid, they’re tenants at will. You issue a thirty-day notice to vacate—has to be in writing, served properly. Certified mail is best. If they don’t leave, we file an eviction suit in justice court. Entire process can take anywhere from four to eight weeks depending on how backed up the docket is.”

“And the money?” I asked.

“The promissory note is enforceable,” he said, tapping the document. “You’re within the statute of limitations. We file a separate civil suit for breach of contract. That’s not quick, but it’s straightforward.”

He hesitated, took off his glasses, and set them on his desk.

“I’m obligated to ask you this,” he said. “Are you sure you want to go down this path? This is your daughter we’re talking about. There’s no unringing this bell once we file.”

“I gave them four years of free rent,” I said. “I gave him $80,000 for his business. I’ve covered their bills, their emergencies, their everything. I walked into a dinner I was invited to at my own house and was told the floor was my place. The bell’s been ringing for a long time, Mark. I’m just finally listening to it.”

He held my gaze for a long moment and then nodded.

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll draft the notice to vacate today. We’ll send it out certified first thing Monday. I’ll also draft a demand letter for repayment on the promissory note. It will lay out exactly how much he owes and how long he has to respond before we file suit. Be prepared for some fireworks.”

“It’s already ugly,” I said. “At least now it’ll be honest.”

An hour later, my signature went onto two more documents. One was the notice to vacate. The other authorized Mark to act on my behalf for both the eviction and the debt collection.

Outside, the morning air bit at my face as I walked to my truck. I sat for a minute behind the wheel, staring at the stack of copies on the passenger seat.

It felt like I’d just pressed a detonator.

On Sunday, my phone lit up half a dozen times with Emily’s name. I watched the calls come and go. I couldn’t do it yet. Not until the papers were out in the world, not until what I knew needed to happen was something bigger than a private argument that could be smoothed over with another check.

On Monday morning, I tracked the certified letter like a hawk. There’s a little thrill when a package gets delivered, a tiny jolt of satisfaction. This felt like that, but sharper.

Out for delivery at 8:15 a.m.

In transit.

At nine forty-seven a.m., the notification pinged.

Delivered. Signature obtained.

I clicked the image.

Michael’s scrawl sprawled across the signature line.

Fifteen minutes later, my phone rang. His name glowed on the screen.

I picked up on the fourth ring and put the call on speaker, set it on my desk next to a stack of invoices from a lumber supplier.

“Yes,” I said.

“Is this some kind of joke?” he demanded. His voice had that forced laugh I’d heard when he talked big with other men. “This eviction notice thing. Ha ha. Very funny.”

“It’s not a joke,” I said. “It’s a legal notice.”

“Come on, Arthur,” he said. “You’re really going to kick your own daughter out over, what, a misunderstanding at dinner?”

“I’m reclaiming my property,” I said quietly. “You have thirty days to vacate.”

“You can’t do this,” he snapped. “We have rights. Tenants’ rights. Squatters’ rights. Whatever.”

“No,” I said. “You have thirty days. The notice explains everything. Read it.”

There was a beat of silence, then a click.

He’d hung up.

The quiet in my office settled heavy for a moment. Out in the shop, I could hear the rhythmic whine of a saw and the deep thud of boards being stacked.

Two hours later, Emily called.

I stared at her name for a heartbeat and then answered.

“Dad, please,” she said. Her voice sounded raw, like she’d been crying or screaming or both. “Please tell me this is a mistake.”

“It’s not a mistake,” I said.

“You can’t do this,” she said. “It’s almost winter. We don’t have anywhere to go.”

“You’ve had four years to figure that out,” I said. “I’ve given you a place to live, rent-free. I’ve covered bills, repairs, everything. I can’t do it anymore.”

“You’re punishing me for what he did at dinner,” she said.

“I’m ending an arrangement that stopped working a long time ago,” I said. “You’re both adults. You can find another place to live.”

“We can’t afford it,” she whispered. “Michael’s business—”

“I know about Michael’s business,” I said. “I invested in it. I’m still waiting to see a return on that.”

“This is about money,” she said, latching onto that word like it was a lifeline. “You’re choosing money over your daughter.”

“I’m choosing not to subsidize my own humiliation,” I said. “You watched him put a plate on the floor for me, Emily. You didn’t say a word.”

“I didn’t know what to do,” she said. “He gets so angry when I contradict him. I just froze. I thought you’d make a joke or something, or—”

“You thought I’d take the plate,” I said, finishing the sentence she couldn’t.

She didn’t answer.

“I’m your daughter,” she said finally, like she was laying down a trump card. “You’re all I have left after Mom.”

“And he’s your husband,” I said. “You chose him over me last night. That’s how it works when you’re married, I get that. Now you live with that choice.”

I ended the call this time.

I set the phone down and waited for my hands to shake.

They didn’t.

That should have been the end of it: a messy, painful family conflict kept mostly private until it was resolved in paperwork and moving boxes.

Michael had other ideas.

The next morning, my secretary, Denise, knocked on my office door.

“Arthur?” she said, hovering in the doorway. “You…might want to check your Facebook.”

I frowned. “I barely use it. What’s going on?”

“We’ve had a few calls,” she said. “Some clients asking if the business is okay. One of them specifically mentioned a post from your son-in-law.”

My stomach dipped.

I pulled up my account, accepted a friend request from a guy I vaguely recognized from one of Michael’s barbecues, and went to Michael’s profile.

There it was.

A long post, carefully composed, the kind of thing you can’t write in one burst of anger. It takes revision.

“My father-in-law is kicking his daughter out of her home during the holidays,” it began. “After years of us taking care of him, helping maintain his property, being there after my mother-in-law passed, he’s decided money is more important than family. He gave us thirty days to leave with nowhere to go. I’ve tried everything to reason with him, but he won’t listen. I’m sharing this because I’m heartbroken and because I believe people should know how quickly family can turn on you.”

There were photos attached.

Emily on the porch, eyes red, arms wrapped around herself. The house behind her at an angle that made it look like it was theirs alone. A shot of their dining room set up beautifully for Thanksgiving—no plastic in sight. A picture of me and Emily at a park years ago, her on my shoulders, both of us laughing.

There was not one word about four years of free rent. Nothing about $80,000 for a “can’t miss” startup. Nothing about a plate on the floor.

The comments were already piling up.

“I can’t believe he’d do that.”

“What kind of father chooses money over his daughter?”

“Disgusting. Do you have a GoFundMe? I’d donate.”

“Sending prayers. Some people have no heart.”

A couple of names I recognized from church wrote things like, “So sorry to hear this, Emily. We’re here for you.”

I felt the anger rise hot and fast, like a flare.

My thumb hovered over the reply box. I wanted to type a list: Four years. $175,000. Plate on floor. Forged deed. Fraud.

Instead, I closed the app and called Mark.

“I figured you’d see it,” he said when he answered. “Don’t reply.”

“You’ve seen it too?” I asked.

“Deborah called me,” he said. “One of your vendors called her asking if you’re having money problems. The post is making its way through the community.”

“He’s painting me as some kind of monster,” I said. “People I’ve known twenty years are commenting like they’re at my funeral.”

“From a legal standpoint, it’s noise,” he said. “From a business standpoint, it’s a headache, I won’t lie. But you responding publicly right now? That gives his lawyer ammunition. He’ll say you’re harassing them, retaliating, whatever. Let him talk. We’ll respond in court.”

“It feels like I’m getting kicked online now too,” I said.

“I get it,” he said. “Men like Michael are good at narratives. They’ve had practice. Let him think he’s winning. The more he talks, the more he locks himself into a version of events that won’t hold up against facts.”

I hung up and tried to focus on work.

It was harder than I wanted to admit.

By lunchtime, the post had been shared sixty times. Someone I’d built a deck for fifteen years earlier called to say he was “sorry to hear things were rough with the family” and how much he’d “always valued our trust.”

By two, my phone buzzed with another call. This time, the number was my accountant’s.

“Arthur,” Deborah said. “I was going through some year-end prep and I need to show you something. It may be nothing, but my gut says it’s something.”

“What kind of something?” I asked.

“Remember when you let Michael help with vendor outreach last year?” she asked. “You gave him access to your email and some of your client list?”

I closed my eyes briefly.

“He said he had marketing experience,” I said.

“Yeah,” she said. “Well, I think he used it.”

Twenty minutes later, I sat in a chair across from her desk while she scrolled through emails on a large monitor.

“Here,” she said, pointing. “This is your email address. But this isn’t your writing style.”

The email on the screen was from “Arthur Evans, Partner, Evans Construction,” but the wording was all wrong. There were too many adjectives. It sounded like a salesman, not a contractor.

“I never wrote that,” I said.

“I didn’t think so,” she said. “Now look at this.”

She clicked. Another email popped up, this one from “Michael Evans, Partner Relations.” It used your letterhead and signature block, but came from a different IP address. He told a client—Thomas Green—that you were semi-retired and that he was handling new contracts. He took a deposit for a home addition that never happened.”

“How much?” I asked, throat dry.

“Twelve thousand,” she said. “Now, here’s another. Maria Castellanos. Promised a store remodel. Eight thousand five hundred in a deposit. No work done. And here’s a third. Jaime Woo. Multi-unit renovation. Fifteen thousand up front. Nothing.”

She clicked through each one, the numbers piling up.

“Thirty-five thousand five hundred dollars,” she said. “All paid to Michael’s personal accounts. None of it went through your business books. The victims either gave up or were told it was a civil matter.”

I gripped the arms of the chair.

“And that’s not all,” she said. “While I was pulling property records for your taxes, I stumbled on a filing in the county’s system. A gift deed, from you to Michael. It attempted to transfer your rental property—your daughter’s house—to him. The county rejected it because the notary license number didn’t match any active notary in the state.”

She clicked again, bringing up a scanned document. My name, my address, my property information. A signature that looked like mine but wasn’t, if you knew your own hand.

“My God,” I whispered.

“They sent the rejection notice to the property address,” she said. “He gets the mail there.”

I stared at the screen, at my own forged signature.

“Why didn’t he tell me?” I asked, immediately realizing how stupid that question was.

“You know why,” she said gently.

The flimsy white plate in the foyer suddenly had company in my head: a piece of paper with my stolen name on it.

“You need to go to the police,” she said. “This goes beyond family drama now. This is fraud. Theft. Forgery.”

I nodded slowly.

That afternoon, I found myself in another chair, this time across from Detective Sarah Morgan of the city’s fraud unit. Her office had that fluorescent hum that seems standard in police buildings. A Styrofoam cup of coffee sat next to her computer, the surface marbled with cooled cream.

“Mr. Evans,” she said, turning on a small digital recorder. “I understand you believe your son-in-law has committed fraud using your business and property.”

“I don’t believe it,” I said. “I’ve seen it.”

We went through everything. Deborah’s printouts. The emails. The bank deposits. The attempted deed transfer. I laid out the timeline as best I could, which cases connected, which clients I recognized.

She listened, took notes, and then started making calls.

The first call was to Thomas Green. He answered on the second ring. On speaker, his voice filled the small room.

“Yes, I remember Michael,” he said. “He told me he was your business partner. Said you were stepping back and he was taking over new projects. I gave him twelve grand for an addition on my house. He never showed. Stopped answering calls. I filed a complaint, but the desk sergeant said it was a civil issue.”

The next call was to Maria. She sounded tired.

“He used your name,” she said. “I figured you were in on it and I just didn’t matter.”

Jaime was the third. His story was almost identical, just with different numbers and a different building.

Each voice stacked another brick on a wall I hadn’t wanted to see.

“This isn’t just a civil matter,” Detective Morgan said when she hung up. “Using someone else’s business identity to obtain money crosses into criminal territory.”

“What happens next?” I asked.

“I’ll write this up and forward it to the district attorney’s office with my recommendation,” she said. “In the meantime, I’ll invite Mr. Leonardo in for an interview. He can choose to cooperate or not. Either way, the paper trail is solid.”

That night, my phone rang again.

“Dad,” Emily said, voice quiet. “The police called Michael. They want to talk to him about fraud. He says you’re making this up to justify what you’re doing.”

“I filed a report,” I said. “He used my name and my business to take money from people. I have their documents, their emails, their bank records. This isn’t something I could fabricate if I wanted to.”

“Are you trying to get him put in… in prison?” she asked, stumbling over the word.

“I’m trying to get some justice for people he hurt,” I said. “What the courts do with that isn’t up to me.”

“He says you’re lying,” she whispered. “He says you’re doing this because you’re bitter and alone.”

The words hit with more force than I wanted to admit.

“Emily,” I said carefully. “How many times has he looked you in the eye and lied?”

There was a long, long silence.

Finally, she said, “How many people?”

“At least four so far,” I said. “Probably more. Deborah’s still digging.”

She exhaled sharply, a sound halfway between a sob and a laugh.

“I need time,” she said. “I don’t know what to think.”

“You take whatever time you need,” I said. “Just remember one thing. The plate wasn’t an accident. Neither was the deed. Neither were those fake emails. They’re all the same man.”

She hung up.

Days blurred into weeks.

Detective Morgan interviewed Michael. He went in with his lawyer, denied everything at first. Then, when confronted with timestamps and IP addresses and signed contracts, started calling it “marketing help gone wrong.” He claimed he “found” the deed that way and “didn’t realize” the signature was fake.

The DA’s office took the case. They filed charges: wire fraud, forgery, theft by deception. The eviction hearing was set for March. Michael’s lawyer, a man named Jimenez, filed motions to delay, filed a counter-claim saying the eviction was “retaliatory” and a response to “family conflict,” tried to use his own client’s social media posts as proof of my bad faith.

The judge denied the motion.

During that time, the social fallout continued. A long-time client pulled out of a pending deck contract “until things settled down.” A neighbor I’d known for twenty years started waving from farther away. Two people, though, did something unexpected: they came by my office, sat in the chair across from my desk, and said, “I don’t know what’s going on exactly, but I’ve known you too long to think you’d just throw your daughter out for fun.”

Those conversations anchored me more than any legal document.

The day of the hearing arrived bright and cold.

The courthouse smelled like floor wax, paper, and coffee. The hallway outside the courtroom was a strip of linoleum, wooden benches lining the walls. People sat clutching manila folders and envelopes, some dressed in suits, some in clothes that looked like they’d been grabbed off a chair that morning.

Michael sat on one of the benches near the courtroom door, wearing a suit that probably cost more than my truck, though it didn’t sit as well now that he’d lost some weight. Jimenez sat next to him, flipping through a file. Michael’s face was carefully composed in what he probably thought of as “injured dignity.”

Emily sat on a bench halfway down the hall, hands clenched around her purse strap. She wore a plain black sweater and jeans. She looked smaller, somehow, like someone had turned down the saturation on her.

I walked in with Mark. My boots sounded too loud.

Michael’s eyes met mine for a moment. Something like hatred flickered there before he smoothed it over.

Emily looked up. Our gazes met. She stood, half took a step in my direction, then stopped. Her eyes were shiny.

“Arthur Evans versus Michael Leonardo and Emily Evans,” the bailiff called, opening the courtroom door.

We filed in.

The judge, a woman named Rivers, sat behind the bench. She was in her sixties, hair cut short, glasses perched low on her nose. Her expression said she’d seen every kind of nonsense people could bring into a courtroom and had no patience left for theatrics.

Mark laid out the facts. The deed showing I was the sole owner. The tax records showing I’d paid every bill. The lack of any lease. The four years of occupancy. The equivalent rent—$1,500 a month, forty-eight months, $72,000.

Jimenez argued loudly that family agreements were different, that there had been a “verbal understanding,” that my eviction was “vindictive” and “retaliatory.”

“Do you have any documentation that your clients paid rent?” Judge Rivers asked. “Checks, receipts, bank transfers?”

“No, Your Honor,” he said. “But it was understood—”

“Understood by whom?” she asked.

“By the family,” he said weakly.

“Family may have understandings,” she said. “The court requires evidence.”

Then Mark introduced the fraud evidence. Technically, it wasn’t strictly necessary for the eviction case, but the judge had agreed to hear limited evidence to assess credibility. The forged deed, the fake emails, the victims’ statements.

“Mr. Leonardo, did you attempt to file a deed transferring this property to yourself using a forged signature and an invalid notary stamp?” she asked.

He shifted in his seat. His lawyer leaned over and whispered.

“On the advice of counsel, I decline to answer,” he said.

“You may invoke your right not to incriminate yourself in a criminal case,” she said. “This is a civil matter. I am allowed to draw negative inferences from your refusal.”

From the gallery, I saw Emily’s shoulders tense.

Fifteen minutes later, the judge ruled.

“Mr. Evans is the legal owner of the property,” she said. “The defendants have no lease and no record of paying rent. They have no legal right to remain. The eviction is granted. The defendants have fourteen days to vacate.”

She banged the gavel.

Just like that, something that had quietly been wrong for four years was formally declared wrong in a room where it mattered.

Outside in the hallway, Emily sat on a bench, staring at the floor.

“You won,” she said when I sat next to her.

“The court agreed with the facts,” I said. “It doesn’t feel like winning.”

“He lied,” she said in a small voice. “About the business. About the deed. About…everything.”

“I know,” I said.

“I defended him,” she said. “On social media. To friends. Against you. I told people you were choosing money over me.”

“You were doing what you thought you had to do to keep your marriage from falling apart,” I said. “You were loyal. That’s not a bad thing. It was just aimed at the wrong person.”

“What do I do now?” she asked.

“Figure out what’s safe and right for you,” I said. “That might mean staying with a friend for a while. It might mean talking to a lawyer of your own.”

“I can’t move back in with you,” she said. “I don’t want you to feel like you’re being manipulated again.”

“You’re my daughter,” I said. “That’s a different kind of arrangement. But you’re also an adult. You get to decide what help looks like. If you want my help, I’ll give it. If you don’t, I’ll respect that.”

She swallowed hard.

“I don’t want to live with him,” she whispered.

I took a business card out of my wallet, flipped it over, and wrote an address on the back.

“I’ve got a small short-term rental across town,” I said. “Company used to use it when we had out-of-town crews. It’s empty now. You can stay there while you figure things out. Rent-free for the first month.”

She took the card like it weighed a hundred pounds.

“Thank you,” she said.

We stood. Mark called to me from across the hallway.

“The DA’s office filed formal charges,” he said when I walked over. “Wire fraud, forgery, theft by deception. Plea deal is on the table. Three years’ probation, restitution to the victims, guilty plea to at least one felony count. His lawyer is…considering.”

I looked back at the bench where Emily sat, card in hand.

“Good,” I said. “He can consider it while he packs.”

You’d think that would be the end of the most dramatic part of the story. But people like Michael don’t fade quietly.

Two days after the hearing, my phone buzzed with a call from Mrs. Lee, my neighbor from the rental property.

“Arthur,” she said, voice crisp. “There’s a moving truck at your place. Two men are hauling your dining set into it. The one you refinished. Is that supposed to be happening?”

My heart dropped.

“Call the police,” I said. “Tell them there may be a theft in progress. I’m on my way.”

I drove faster than I had in years, old habits from my days as a younger man coming back. The speedometer climbed. I ignored it.

A box truck sat in my driveway when I pulled up, backed almost to the garage. Two men in work gloves were carrying the carved oak chairs my father had left me. Michael stood by the ramp, directing them like a foreman on a jobsite.

“Put that one in the back corner,” he said. “Be careful with the desk. That’s an antique.”

I parked my truck sideways across the driveway, blocking the box truck.

The movers stopped. Michael turned, saw me, and his face darkened.

“Arthur, move your truck,” he said. “We’re moving our stuff.”

“That’s my furniture,” I said, getting out. “I owned that dining set before Sarah died. Before you ever showed up at my house.”

“It’s in my house,” he said. “It’s mine now.”

“You’re leaving in twelve days,” I said. “You’re not taking my things with you.”

“Possession is nine-tenths of the law,” he said, smirking. “You can look it up.”

“You’ve already demonstrated your grasp on legal concepts isn’t great,” I said. “If you try to take that, I’ll add theft to the list the DA’s looking at.”

One of the movers shifted nervously. “You said this was all yours,” he said to Michael.

“It is,” Michael said. “He’s just trying to scare you.”

Sirens grew louder in the distance. A patrol car pulled up a moment later, blue and red lights washing the front of the house. It was Officer Hayes, same one who’d been there when we served notices.

He listened to both our versions, took note of the furniture, then walked through the house with me. Mrs. Lee came over with a folder of photos she’d printed out—pictures of me moving that furniture in years ago, Emily as a teenager carrying cushions, Sarah standing with a paintbrush in hand.

Between that, my old holiday photos on the walls, and the fact that Michael couldn’t produce a single receipt showing he’d ever paid for any of it, Hayes told the movers to put everything back inside.

“If you remove it,” he said, “you may be participating in a theft. I suggest you unload it and leave. You can work out your pay with your client later.”

The movers didn’t need more than that. They unloaded the truck, set the furniture back inside, and left quickly.

“You’re insane,” Michael hissed at me after the officer went back to his car. “All this over some wood and a house.”

“This is who you are,” I said. “Take a good look. Because it’s who the court’s going to see too.”

He stared at me, eyes bright with rage.

“You destroyed my life,” he said.

“You destroyed your own life,” I said. “I just stopped funding it.”

Officer Hayes documented everything and left. Michael went back into the house and slammed the door.

The next days were quiet on the surface. Too quiet. It felt like the calm before a storm.

The DA’s office set a date for Michael’s arraignment. His lawyer tried to get the charges reduced. There were rumors about him trying to borrow money from anyone he could still charm—friends, distant relatives, even one of the very clients he’d scammed.

Then, on the morning of the fourteenth day, I arrived at the house with a locksmith and Officer Hayes. The driveway was empty. The curtains in the front windows were open. No cars. No signs of life.

Hayes knocked. No answer. We entered with my key.

They were gone.

Drawers hung half-open. Closets were stripped of clothes. Anything portable and obviously theirs was missing—Emily’s framed photos, Michael’s gadgets, their cheap couch. Anything that was mine and not bolted down had been either left or destroyed.

Holes in the drywall big enough to put your fist through, though I suspected they used something heavier. Cabinet doors ripped off hinges. Carpet stained and hacked at. A pendant light over the dining room was shattered, glass on the floor.

It was vandalism, pure and simple.

In the primary bedroom, lying alone on the floor like a snake, was a single piece of paper.

I picked it up.

You chose him. You’ll regret it. I’ll be back when you realize your mistake.

It was addressed to Emily.

I took a photo, texted it to Mark, then folded the note and slid it into the folder with Eric’s other greatest hits.

“This house has good bones,” I told Hayes, more to myself than to him. “It can be fixed.”

“It deserves better owners,” he said.

A few hours later, while I was measuring damaged sections of wall and making a list of supplies, my phone buzzed.

“Dad,” Emily said. “Can we talk? I need to see you about something.”

“Where are you?” I asked.

“Coffee shop on Fifth,” she said. “Michael’s here. I told him I’d only meet him somewhere public with my friend Sarah. I… I don’t know what to do.”

“Text me the address,” I said. “I’m on my way. Don’t leave with him. Promise me.”

“I promise,” she said.

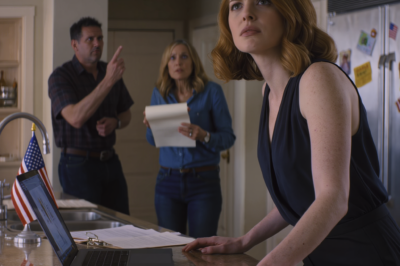

And that’s how we ended up in that coffee shop, with the American flag magnet crooked on the door and the bad jazz playing and my daughter finally seeing her husband clearly.

When I walked in, the barista looked up with that bored interest people get from watching a small-town drama unfold over multiple visits. Emily sat at a corner table, Sarah beside her. Michael sat at the next table, angled like he wanted to be close but not too close.

As I crossed the room, Michael stood.

“This doesn’t concern you,” he said. “This is between my wife and me.”

“It concerns me if she’s afraid,” I said.

“I’m not afraid,” Emily said, though the way her hand gripped her cup said otherwise. “I’m done being afraid.”

Sarah stood too, positioning herself slightly in front of Emily.

“You’re poisoning her against me,” Michael said to me. “You’ve always hated me.”

“I hated a man who put a plate on the floor for me,” I said. “I hated a man who used my name to steal from people. Don’t make this about me. This is about you and the man you’ve chosen to be.”

Emily lifted her chin. “Dad didn’t show me those emails,” she said. “He gave them to me. I read them myself. I called Maria and Thomas and Jaime. Michael, you took their money and never did the work.”

“I was going through a rough patch,” he said. “Business gets messy. They knew the risks.”

“You filed a fake deed to our house,” she said. “You forged my father’s signature.”

“I was protecting us,” he said. “If something happened to him, I didn’t want us thrown out on the street. I did it for you.”

“You did it for yourself,” she said. “You always do everything for yourself.”

He reached for her hand. She pulled it away.

“I have nothing,” he said, putting on the vulnerability he’d worn so well at the start of their relationship. “Nowhere to go. You’re all I have. You’re my wife. Doesn’t that mean anything to you?”

“It means I promised to stand by you,” she said. “I kept that promise even when you were lying to me. Even when you were lying about my father. Even when you humiliated him. I broke myself trying to keep that promise. You used it as a shield.”

“We’re in this together,” he said. “We always have been.”

“No,” she said. “I was your shield. You hid behind ‘us’ while you did whatever you wanted.”

He leaned closer, voice dropping.

“You walk away from me,” he said, “you’ll regret it. You’re not strong enough to make it without me.”

Sarah’s phone was out, camera pointed at him.

“Back off,” she said. “You’re being recorded.”

Michael looked around. The barista was watching. The couple at the next table had stopped pretending to read.

He realized the performance wasn’t going the way he’d planned.

“You’ll all regret this,” he muttered, stepping back.

He walked out, shoving the door open. The little flag magnet wobbled on the frame. A moment later, we saw his dented sedan pull away through the window.

The room exhaled.

Emily sank into her chair. Her shoulders shook once, twice, as if her body was letting go of some tension it had been holding for years.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “For everything. For Thanksgiving. For believing him. For that post.” Tears spilled over onto her cheeks. “I made you into the villain in my head because it was easier than seeing who he was.”

“You were trying to protect the life you’d built,” I said. “That’s what people do. We defend what we’re invested in, even when it hurts.”

“I chose him over you,” she said. “Over and over. Even when my stomach hurt from the things he said about you. I still defended him.”

“You chose hope,” I said. “You chose the version of him you fell in love with. The nice guy with plans and promises. It’s not stupid to want that to be real.”

“I don’t know how to be alone,” she said. “I went from home to college to him. I don’t know what it means to just be Emily.”

“I didn’t know how to be alone either when your mom died,” I said. “I had to learn. It sucked. It wasn’t romantic. It was just putting one foot in front of the other every day until it felt less like walking on glass.”

She took off her wedding ring.

It was a simple band, the same one I’d helped her pick out years ago when money was tight but love was big. She rolled it between her fingers, stared at it for a long moment, then set it gently on the table between us.

“I don’t want it,” she said. “But I’m not ready to throw it away.”

I picked it up and slipped it into my pocket with my keys.

“I’ll keep it,” I said. “When you’re ready to decide what to do with it, we’ll figure it out.”

“Can Mark recommend a divorce lawyer?” she asked. “I don’t want to make more mistakes.”

“I’ll ask him,” I said. “We’ll find somebody good.”

She wiped her eyes with a napkin.

“Dad?” she said.

“Yeah?”

“Can I…come over for dinner sometime?” she asked. “Just us. Real plates. Not the fancy stuff. Just… normal.”

Normal sounded like a luxury.

“Anytime,” I said. “You’re always welcome at my table.”

That Sunday, my little apartment smelled like roast chicken, garlic, and rosemary. Sinatra played quietly from a small speaker on the counter, “The Way You Look Tonight” drifting through the room. The table was set with two solid ceramic plates, the good ones I’d bought after Sarah died to stop myself from eating over the sink like a bachelor.

When Emily walked in, she stopped in the doorway and took it all in.

“Smells amazing,” she said.

“Nothing fancy,” I said. “Just the basics.”

She looked at the plates, the knives and forks, the folded paper napkins.

“Real plates,” she said softly.

“Never going back to plastic,” I said.

We sat. For a while we just ate, the sounds of forks on ceramic and Sinatra’s voice filling the spaces where we didn’t yet know what to say.

Eventually, the conversation came.

She told me about the early days with Michael, the charm, the jokes, the little acts of chivalry. I told her about the early days with her mother—the broken-down car on our first date, the burned casserole we pretended tasted good.

She told me about the first time Michael raised his voice at her, the way he made her feel like it was her fault afterward. I told her about the first time I realized he was watching my wallet more closely than he watched her.

She told me she’d hired a therapist. I told her I was proud of her in a way that had nothing to do with grades or jobs or relationships.

She told me that reading the email printouts had made her physically sick. I told her that seeing my own forged signature had done the same.

When we’d finished eating, she leaned back in her chair and looked at me.

“You kept records,” she said. “That’s what saved you. And your house. And me.”

“I’m a contractor,” I said. “You don’t survive long in this business if you don’t keep receipts.”

She laughed, a short, surprised sound.

“It’s more than that,” she said. “Mom used to say you kept everything. Notes, receipts, ticket stubs, little scribbles. I used to think it was silly. Now I’m grateful.”

“Your mom was a better judge of character than I was,” I said. “She had her doubts about him from the start.”

“Why did you ignore her?” she asked.

“Because I wanted you to be happy,” I said. “Because I saw you laughing and thought that had to mean something. Because I thought I could keep an eye on him if he was close.”

She nodded slowly.

“The DA’s office offered him a deal,” I added. “Mark texted me earlier. Three years’ probation, full restitution to the victims, guilty plea to felony fraud.”

“Is he going to take it?” she asked.

“His lawyer says he doesn’t have much choice,” I said. “The evidence is strong. The victims are willing to testify. If he goes to trial and loses, he’s looking at time in a cell instead of time reporting to a probation officer.”

She stared at the table for a long moment.

“I loved him,” she said. “Or I loved who I thought he was. I hate that part of me still feels sorry for him.”

“That part of you is human,” I said. “Just don’t let it write any more checks.”

She smiled faintly.

A year later, the house was rented out to a nice young couple with a baby on the way. The drywall was patched, the cabinets rehung, the carpet replaced. The dining room saw holiday meals again, but this time I saw them through pictures Emily texted me when her friends came over to help with decorating between tenants.

Michael took the plea. He avoided prison, but every month a portion of whatever money he could scrape together went into a court-controlled account to repay what he’d taken—from Thomas, from Maria, from Jaime, from the contractor whose tools he’d “borrowed,” and from me.

He was still paying off $175,000 in different forms: restitution, civil judgments, the invisible tax of a ruined reputation.

Sometimes on holidays, I’d see his name pop up on social media in some rant about “a system rigged against hard-working men.” Usually, it had three likes, two of them from anonymous accounts and one from some guy who sold nutritional supplements.

Emily got divorced.

She moved from the short-term rental into a small place of her own—a one-bedroom with cracked tile and good light. She got a job at a nonprofit she’d always admired but never thought she could afford to work for. She adopted a cat and named it Sinatra because “he complains a lot but he’s got a good heart.”

Every Sunday, she came over for dinner.

We tried different recipes. Sometimes we burned things. Sometimes we ordered takeout. Sometimes we just made sandwiches and watched old movies on my too-small television.

But every Sunday, there were two solid plates on the table. Two sets of silverware. Two glasses of iced tea or wine.

One Thanksgiving, a couple years after the plate on the floor, we decided to cook together at my place instead of her going to anyone else’s.

She showed up with bags of groceries, hair pulled back, sweatshirt dusted with flour like she’d already been wrestling with dough.

We spent the afternoon in my little kitchen. Sinatra the cat wound himself around our ankles and tripped us at every opportunity.

At one point, she leaned against the counter, breathing in the smell of roasting turkey.

“Do you ever miss it?” she asked. “The old house. The big table. The…idea of it all?”

I thought about three cars in my driveway and a cheap plastic plate on a hardwood floor.

“Sometimes I miss the house,” I said. “We built a lot of memories there. Good ones. I miss your mom’s laugh echoing off those walls. I miss seeing you come down the stairs on your way to prom like you were about to fly out the door.”

She smiled at the memory.

“But I don’t miss pretending,” I added. “I don’t miss being in a place where my presence was tolerated instead of wanted.”

She nodded.

“I used to think a big house full of people meant we were winning at life,” she said. “Now I think having one person who actually sees you and doesn’t use you is worth more.”

“That’s a much more affordable dream,” I said.

She laughed.

When the turkey was done, we set the table.

I took two ceramic plates from the cabinet. They were a little chipped now, but solid. I ran my thumb around the rim of one, feeling the weight.

“Do you still have any of those plastic plates?” she asked suddenly.

I opened a cabinet above the stove. Way in the back, behind an old mixing bowl, sat a small stack of them, dusty and bent.

I pulled one out and set it on the counter.

“Why do you still have these?” she asked.

“Maybe I kept them as a reminder,” I said. “Of what I won’t accept anymore.”

She picked the plate up, turned it over, pressed the center gently until it bowed.

“It feels like a lie,” she said. “Like something pretending to be useful that collapses if you put real weight on it.”

She set it in the trash can and dropped the lid with a soft thud.

“Where it belongs,” she said.

We carried the real plates to the table.

As we sat down, Sinatra the cat jumped up on a chair, eyeing the turkey as if he’d been invited.

“Don’t even think about it,” Emily told him.

He blinked slowly and stayed.

We held hands across the table for a moment.

“I’m grateful,” she said.

“For what?” I asked.

“For you keeping records,” she said. “For you walking out that night instead of taking the plate. For you choosing yourself, because if you hadn’t, I’d still be choosing him.”

“I’m grateful you came to that coffee shop,” I said. “And that you promised you wouldn’t leave with him.”

She smiled.

“Happy Thanksgiving,” she said.

“Happy Thanksgiving,” I said.

Outside, someone down the block cranked up Sinatra’s “Come Fly With Me.” Through the open window, the sound of kids tossing a football drifted in with the cool air. Somewhere, there were probably three cars parked at stupid angles in somebody’s driveway.

Here, there were two steady chairs, two real plates, and a daughter who looked me in the eye without flinching.

In the end, that was the only kind of wealth that mattered.

And that flimsy plate on the floor—the one meant to humiliate me—became nothing more than a broken piece of plastic at the bottom of a trash can and a story we told sometimes, quietly, to remind ourselves how far we’d come and how much we’d paid to sit at a table that didn’t collapse under the weight of the truth.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load