There was a tiny American flag stuck into the corner of the paper plate in front of me, the kind you buy in packs of a hundred at Walmart around the Fourth of July. It leaned against a pile of potato salad and a slightly overcooked hot dog, ketchup bleeding into the bun. Country music hummed from a Bluetooth speaker, kids ran through sprinklers in the Caldwells’ perfectly manicured yard, and there was a cooler full of light beer sweating in the July heat. On the surface, it was the most ordinary suburban barbecue in America. On the inside, it was the moment my life quietly split in two.

“If you walked away tomorrow, no one would even notice,” my sister-in-law said, loud enough for the whole table to hear.

Everyone laughed.

Everyone but me.

I lifted that hot dog with the sad little flag toothpick, met Amanda’s eyes, and said clearly, “Challenge accepted.”

By midnight, I was planning my escape. By sunrise, my entire life fit into the back of my car. And exactly fifty-two weeks later, I walked into a hotel ballroom in Seattle as a different woman, ready to find out whether she’d been right—whether I could disappear and it wouldn’t matter—or whether I could build a life where my presence finally counted.

That day at the barbecue was the moment I stopped begging to be seen.

My name is Vanessa, I’m thirty-four, and when all of this started, I’d been married to Gregory Caldwell for seven years. On paper, it sounded like a solid life. We had a comfortable house in the suburbs outside Boston, a joint savings account, decent cars, and a kitchen full of wedding-registry gadgets we barely used. I ran a small graphic design business from home; Gregory climbed the ladder in his father’s marketing firm.

The trouble was never the house, or the money, or even the long hours. The trouble was the way I never stopped feeling like a guest in my own life.

We met during our last year of college. I was juggling a full course load in graphic design and pulling espresso shots at a campus coffee shop to keep my student loan balance from exploding. He walked in one night around 11 p.m., wearing a faded Red Sox hoodie and looking like he hadn’t slept in two days.

“What’s good that’s going to keep me awake and not make me hate myself tomorrow?” he asked, leaning on the counter.

“Coffee,” I said. “That’s the whole point.”

He laughed, that easy, confident laugh that came from never worrying about things like overdraft fees or rent. We started talking about the book I was reading behind the register—some design theory text that most people found boring. He didn’t. Or at least he was good at pretending he didn’t.

Within a month, we were studying together. Within three, we were inseparable. He was finishing a business degree, funded comfortably by his parents. I was sketching logo concepts on the backs of receipt paper between customers. He talked about mergers and market share; I talked about fonts and color psychology. It felt like a good balance back then.

By graduation, he proposed with a ring that, as I learned later, cost more than my entire student debt. That number was a little over $42,000. The ring was more. I should’ve seen the imbalance in that, but all I saw was a man on one knee in front of the fountain on the quad while our friends cheered, holding out something sparkling in a velvet box.

I said yes before he could finish the speech.

When we got married a year later, I thought I was gaining more than a husband. I thought I was gaining a family. The Caldwells were everything my family wasn’t: affluent, well-connected, polished in that old-money New England way. Richard, my father-in-law, had built Caldwell Marketing Group from a tiny two-man shop into a multi-million-dollar firm. Patricia, my mother-in-law, treated their sprawling colonial house like a stage and herself as the director, managing social events with military precision while serving on three charity boards.

Amanda, his sister, was already a junior executive at the firm by twenty-seven, sharp as glass and just as cold when she wanted to be. Michael, the younger brother, was the “family rebel” who still somehow landed a cushy job at an uncle’s investment firm and a BMW for his thirtieth birthday.

My background was a different planet.

I grew up in a two-bedroom apartment over a laundromat, raised by a single mom who worked double shifts at the hospital cafeteria and cleaned office buildings on weekends. My younger sister Olivia and I shared a room until I left for college. Holidays meant potluck dinners with neighbors and homemade gifts Mom crafted at the kitchen table after we went to bed.

The first time I walked into the Caldwell house, I felt like I’d stepped onto the set of a movie. There were framed degrees from Ivy League schools lining the hallway, a baby grand piano in the living room no one actually played, and a fridge so big it could’ve doubled as a walk-in closet.

They were polite. Patricia called my designs “so creative and fun,” the way you talk about a kid’s art project. Richard asked questions about my work at dinner, then proceeded to explain basic marketing concepts to me with the tone of a professor correcting a freshman. Amanda smiled with all her teeth and corrected my pronunciation of wine varieties like she was doing me a favor.

“They mean well,” Gregory would say when I brought it up later. “Amanda’s just trying to help you fit in. That’s how she shows love.”

Her love felt like being slowly dissolved in acid.

At our wedding, Amanda’s maid of honor speech included not one, not two, but three little stories about Gregory’s ex-girlfriends. “Just to show how lucky he is that he finally found the one who stuck,” she said, and everyone laughed. I laughed too, the way you do when you feel like the only person who doesn’t get the joke.

When we announced we were buying our first home, she tilted her head. “Are you sure that neighborhood is really the right fit for a Caldwell?”

When I signed my first big branding client—a boutique gym downtown—she asked, “Do you think they hired you because of your portfolio or because they know who your father-in-law is?”

Each comment alone was small. Together, over time, they were like a constant drip of water on stone, carving away at something solid in me.

I tried anyway. God, I tried.

I volunteered for Patricia’s charity luncheons, arranging centerpieces and designing invitations for free. I referred smaller clients to Richard’s firm when projects were too big for me. I remembered every birthday, every anniversary, bought thoughtful gifts, showed up on time, dressed carefully in the understated neutral tones Patricia favored. I laughed at inside jokes I didn’t understand. I Googled designer names and wine regions at midnight so I wouldn’t look lost at their dinner table.

Every time I voiced discomfort, Gregory had an excuse ready.

“That’s just how Dad is.”

“Mom’s under a lot of stress organizing the gala.”

“Amanda’s competitive with everyone, not just you.”

I believed him because I wanted to.

For the first few years, I kept my freelance business going, slowly building a client list. I wasn’t rolling in cash, but I was proud that in one year I invoiced just over $67,500 all on my own name. I created brands for local bakeries, yoga studios, a small theater company. People recommended me to their friends. My work showed up on storefronts, menus, websites.

Then Richard dangled an expansion opportunity in front of Gregory, a chance to grow his division if he agreed to travel more—Tokyo, London, San Francisco. It was just… assumed that I’d scale back my work to make that possible. No one sat me down and asked. The conversation went more like, “This is huge for us,” and “You’re so flexible with your work, thank God,” and “It’s just a few years until we’re really set.”

So I scaled back. I let clients go. I stopped attending networking events. Our home became Gregory’s crash pad between flights. My calendar shrank as his filled up.

Then, last spring, at just under eleven weeks, I lost a pregnancy we’d barely begun to talk about out loud.

The physical pain was one thing—bloody, messy, disorienting. The emotional aftershock was worse. Gregory was in Chicago for a conference. He offered to come home, but there was something in his voice, some tiny exhale of relief when I said, “It’s okay. I’ll manage.”

Patricia sent flowers with a card that read, “Perhaps it’s for the best until you’re more settled.”

Amanda texted, “Maybe when you’re less stressed trying to juggle your little business, things will go better. Focus on family first.”

Only Olivia showed up. She got on a plane with two days’ notice, bringing homemade chicken noodle soup in Tupperware and a playlist of comfort movies. She slept on our couch for a week, holding me when I cried and saying things like, “You’re allowed to be wrecked. You don’t have to be gracious about this.”

The contrast between her uncomplicated care and my in-laws’ clinical distance cracked something deep inside of me.

I covered it over. I went back to being “fine.” I tucked the grief away in the same place I’d been storing my resentment: somewhere behind my ribs where it could ache without showing. Life went on. Or at least it looked like it did.

By the time Gregory’s parents sent out the email about their annual summer barbecue, I was a smaller, quieter version of myself. My design work had turned into autopilot tasks for a handful of loyal clients. My closest friendships had thinned to occasional texts. My marriage felt like a script we were both reading from out of habit.

And still, I hoped that maybe, just maybe, this year would be different.

The Caldwell Summer Barbecue was a neighborhood institution. Patricia planned for weeks: menu spreadsheets, floral samples, a Pinterest board for table settings. Richard ordered a new imported smoker every other year, it seemed, treating them like trophies. Dozens of guests floated in and out: extended family, business associates, country club friends, neighbors whose names I never fully learned.

This year, I decided, I would bring something unmistakably me.

So that morning, I spent three full hours making my grandmother’s strawberry shortcake from scratch in our kitchen. It was the only dish the Caldwells had ever complimented without that faint note of condescension. I used real whipped cream, macerated the berries with a little sugar and lemon, baked the biscuits just until golden. I arranged everything on the chipped white platter that had belonged to my grandmother and tucked it into a carrier.

That platter was the closest thing I had to an heirloom.

“Ready?” Gregory called from the hallway as he checked his watch. He was already in a pale blue polo and khakis, the official Caldwell man summer uniform.

“Almost,” I said, smoothing the sundress I’d bought specifically because it fit Patricia’s version of “casual but elegant.” It was yellow with tiny white flowers, cheerful in a way I didn’t quite feel.

On the drive over, Gregory talked about his upcoming trip to Tokyo, rattling off details about meetings and time zones. When I asked if we could talk later about me rebuilding my client base, he said, “Sure, but let’s not get heavy before the barbecue, okay?”

“Remember,” he added as we turned onto his parents’ street, flags fluttering from mailboxes and porches, “Dad’s unveiling his new smoker today. Try to act impressed even if you don’t get why it’s a big deal.”

“Got it,” I said. That flag on the mailbox, the same stars and stripes as the tiny one stuck in the hot dog I’d raise later, flickered by my window as if it were watching.

When we walked through the side gate into the backyard, the party was already in full swing. Caterers in black polos moved between white-clothed tables carrying trays of sliders and skewers. Richard stood near the grill island on the stone patio, surrounded by men in polos and boat shoes admiring the new smoker like it was a luxury car. Patricia floated from group to group in a navy wrap dress, her laugh delicate and practiced.

“Greg!” Amanda’s voice cut through the noise. She appeared from the crowd in a white sundress that probably cost more than my entire outfit. She air-kissed both his cheeks, then let her eyes sweep over me.

“Vanessa. That dress is so cheerful,” she said, like she was talking to a child who’d drawn on the walls. “The kitchen’s getting crowded, but I’m sure you can find somewhere to put your… contribution.”

Before I could answer, she looped her arm through Gregory’s and pulled him toward a cluster of people near the bar, launching into a story about running into one of his college buddies at the gym.

I stood alone by the gate, holding my strawberry shortcake in both hands like it was a shield.

In the kitchen, Patricia was directing the catering staff with the intensity of a general.

“Oh, Vanessa, dear,” she said when she noticed me. “You didn’t need to bring anything. We have the pâtisserie handling desserts.” She gestured vaguely toward the pantry. “But how thoughtful. Just put it in there for now.”

The “for now” was doing a lot of heavy lifting.

I set my grandmother’s platter gently on a shelf already crowded with other dishes guests had brought—store-bought brownies, a homemade pie, a trifle in a glass bowl. I watched as Patricia turned to a server and said, “Make sure there’s room for Amanda’s tiramisu in the center of the dessert table. It’s authentic, from her friend’s recipe.”

My shortcake sat in the pantry, out of sight.

That was the first time that day I thought, I am not part of this family.

The next two hours blurred into a montage of almost-conversations and half-smiles. I tried to help set up the buffet; the caterers waved me off. I approached a group discussing a movie; Amanda slid into the circle and redirected the topic to someone’s vacation home in the Hamptons. Every time I found someone who seemed genuinely interested in my work, Patricia swept them away to meet “someone you just have to know.”

Michael’s wife, Charlotte, got the opposite treatment. She’d only been married into the family for two years, but Patricia introduced her to everyone as “our Charlotte, the pediatric surgeon,” saying the “our” with deliberate pride. Amanda folded her into stories about family vacations Charlotte hadn’t been on, as if she’d always been there. Even Richard asked about her latest rotation at the children’s hospital, listening like he actually cared.

I watched from the sidelines, feeling like the understudy no one bothered to call when the lead got sick.

By the time lunch was ready, Gregory reappeared at my side, smelling faintly of smoke and cologne.

“Having fun?” he asked, already steering me toward the buffet line with a hand on my back. He didn’t wait for my answer.

We filled our plates and joined the main table on the patio, the “family” table. I ended up between Uncle Frank, who was hard of hearing and more interested in the brisket than in conversation, and an empty chair reserved for Amanda. Across from me, Gregory sat between Richard and Patricia, already talking about Japanese business etiquette.

Amanda arrived a few minutes later, placing her plate down and immediately commanding the table’s attention with a story about spotting a minor celebrity at her gym. People leaned in. There were laughs, reactions, questions. When she talked, the world shrank down to the space around her plate.

During a lull, I tried to slide into the conversation.

“I actually just finished a branding project for that new bakery downtown,” I said. “They’re having their grand opening next weekend. I—”

Amanda cut me off with a little sigh.

“Is that the place with the neon sign?” she asked. “It’s… a choice.”

“The signage is actually vintage-inspired,” I said, keeping my tone even. “The building used to be one of the first—”

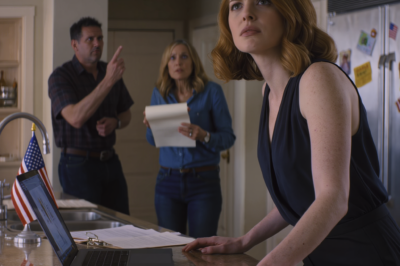

“If you disappeared tomorrow,” she interrupted again, louder this time, with a dramatic roll of her eyes, “no one would even notice. That’s how boring this conversation is.”

For a second, everything went quiet. Then the laughter hit.

Patricia tittered behind her cloth napkin. Richard guffawed. Michael snorted. Even Gregory smiled and reached for his beer. Uncle Frank, who probably hadn’t heard a word, chuckled just because everyone else did.

It felt like someone had dumped a bucket of ice water over my head.

I could feel my face getting hot, my hands going cold. I registered the American flag toothpick stuck in my hot dog bun, the condensation ring from my plastic cup on the table, the way Amanda’s mouth curved in triumph.

Seven years of tiny cuts suddenly added up.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t slam my fork down. I didn’t accuse anyone of anything. I knew how that would go—how the story would be told later about how “Vanessa overreacted again,” “Vanessa can’t take a joke,” “Vanessa is so sensitive.”

Instead, I picked up my hot dog like it was a champagne flute, lifted it slightly, and said clearly, “Challenge accepted.”

The words slid out calm and smooth, but inside, something tectonic shifted.

For a split second, Amanda looked thrown. Then Patricia chirped, “Who’s ready for Richard to carve the brisket?” and the conversation jumped tracks. The moment seemed to vanish, swallowed by the noise of the party.

But it hadn’t vanished for me.

The rest of the afternoon, I moved through the party like a ghost. I watched Gregory move easily through clusters of people, clapping shoulders, making jokes, collecting admiring looks from older men who saw themselves in him. I watched how everyone automatically made room for Amanda in any group she approached. I watched the way people’s eyes slid over me, friendly but detached, like I was an accessory rather than a person.

And under all of it, a steady thought kept repeating: You deserve better than this.

That thought scared me more than Amanda’s words ever could.

On the drive home, Gregory scrolled through his phone at a red light, half-listening as I stared out the window.

“You’ve been quiet,” he said eventually, tossing the phone into the cupholder. “Everything okay?”

“Amanda’s joke,” I said. “Did you think that was funny?”

He sighed, like we’d been here a thousand times. “Vanessa, don’t start. She was just being Amanda. She’s always extra at family stuff. You know that.”

“You laughed,” I said.

“It was a joke,” he repeated. “Not everything needs to be analyzed to death. Why do you always do this on the drive home? It was a nice day.”

Nice day.

He pulled into our driveway and unbuckled his seat belt, conversation over in his mind.

I unbuckled mine too, but the conversation in my head had only just started.

We went through the motions that evening like any other: leftovers for dinner, Netflix murmuring in the background, Gregory checking emails during commercials. At ten-thirty, he kissed my forehead and said, “I’ve got golf with Dad in the morning, so I’m gonna crash.”

He fell asleep within minutes.

I didn’t.

I lay in the dark, staring at the ceiling, replaying not just the barbecue but the past seven years: the comments, the corrections, the way I’d slowly shifted myself to fit around their edges until I couldn’t recognize my own outline. I thought about my grandmother’s strawberry shortcake, sweating in the pantry while Amanda’s tiramisu took center stage. I thought about the baby I’d lost, the flowers with the note that said “perhaps it’s for the best.” I thought about how, in a family where I’d done everything to belong, Amanda could still say that if I disappeared, no one would notice—and everyone laughed.

Around two in the morning, I realized I believed her.

Not in the way she meant it—not that I was boring or worthless—but that in their world, I was optional. Replaceable. Peripheral.

The only question was whether I wanted to stay optional in a life that was supposed to be mine.

I slipped quietly out of bed and padded down the hall to my home office. The blue light from my laptop felt harsh in the dark, but the moment I opened it, a strange calm settled over me.

I started with the banking app. I checked every account we had: checking, savings, credit cards. The joint savings balance blinked back at me—just under $84,000, built over years of careful budgeting and Gregory’s bonuses. Half of that was legally mine. I’d contributed in invisible ways, sure, but also in very visible, invoice-documented ones.

I opened another tab for apartment listings in Seattle, where Olivia lived. Then a tab for long-distance bus routes and flights. Then one for freelance platforms I’d dabbled in but never fully committed to.

By dawn, I had a rough plan. Not perfect. Not polished. But enough.

Gregory kissed me on autopilot before leaving for golf at 8 a.m. He didn’t notice that my eyes looked different, that my voice was softer but steadier when I said, “Have fun.”

The second his car pulled away, I got to work.

First call: Jessica, my college roommate, the kind of friend who survives marriage, distance, and all the excuses you make when you’re trying not to admit you’re unhappy.

“I need a huge favor,” I said when she answered, voice trembling despite my best effort.

“Name it,” she said without hesitation.

“I’m leaving Gregory today. I need help packing the essentials. I’ll explain when you get here.”

There was a tiny pause, then, “Text me your address again. I’ll be there in two hours. I’m stopping for coffee and boxes.”

In the time it took for her to arrive, I made lists. Important documents. Sentimental items. Work equipment. Clothes. Things that were mine before Gregory. Things I’d bought with my own earnings.

When Jessica showed up, arms full of cardboard boxes and iced lattes, she took one good look at my face and said, “Okay. We’re doing this.”

We worked with quiet efficiency. Clothes first—enough for a few weeks. Then my laptop, external hard drives, sketchbooks, drawing tablet. The framed photo of my mom and me in front of the laundromat, both of us holding up my acceptance letter like a trophy. The chipped strawberry shortcake platter—wrapped in dish towels and tucked between sweaters like a relic.

“Leave the fancy stuff,” Jessica said when I hesitated over a set of expensive knives Gregory’s parents had given us. “If you didn’t buy it, you don’t need it. Not right now.”

While she taped boxes and labeled them in her impossible neat handwriting, I sat at the dining table with my laptop and handled the money. I transferred exactly half of our joint savings—$42,000—to my personal account. No more, no less. I paid my share of the mortgage and upcoming utilities. I printed confirmation pages for everything and tucked them in a folder with our marriage certificate.

By three in the afternoon, my car was packed with the essentials. The house looked mostly the same—couch still in place, dishes still in the cabinets, framed wedding photo still on the hallway table. It felt surreal, like I was walking through a life I’d already left.

Jessica hugged me so hard my ribs hurt.

“Call me when you get where you’re going,” she said. “And Vanessa?”

“Yeah?”

“I’m proud of you. You should’ve thrown that hot dog at her, but this is better.”

After she left, the silence pressed in.

I went into the kitchen and wrote Gregory a letter. I told him I needed space to evaluate our marriage. I said I’d taken only what was mine and what I needed to start over. I explained that I wanted no contact for a while—not because I hated him, but because I needed a life where I wasn’t constantly trying to pass an exam I hadn’t signed up for.

I didn’t tell him where I was going.

I took off my wedding ring—the Caldwell family diamond he insisted on upgrading my original ring to—and set it on top of the letter. Next to it, on a separate sheet of paper, I wrote:

“If you disappeared tomorrow, no one would even notice.”

Then I wrote the date, the place, and “Amanda’s comment, family barbecue.”

I wasn’t being petty. I wanted a record, in his own home, of the moment that finally made me leave.

Before I walked out, I picked up the wedding photo from the table. We looked so fresh in it—me with my hair in loose waves, eyes bright; Gregory with his tie slightly crooked from dancing, grin wide. I put the frame back down carefully.

“Goodbye,” I whispered to the empty hallway.

Then I walked out the front door, locked it behind me, and didn’t look back.

Driving away from our neighborhood felt both like fleeing a crime scene and being released from prison. My hands shook on the steering wheel, but with every mile marker, the knot in my chest loosened a fraction. I crossed from Massachusetts into New York, then into Pennsylvania, then further west, the GPS quietly recalculating every time I stopped for gas or bad fast food.

That first night, I checked into a mid-range hotel off the interstate, paid with the credit card I’d kept separate throughout our marriage, and sent two texts: one to my mom, one to Olivia.

“I’m safe. I left. Please don’t tell Gregory where I am. I’ll call when I’m ready.”

I turned my phone off after that. I didn’t want to see the messages I knew were coming.

In the bland hotel room, with its generic artwork and humming air conditioner, I slept thirteen straight hours. It was the deepest sleep I’d had in years.

The next morning, when I turned my phone back on for a moment, the notifications flooded in.

Gregory:

“Where are you?”

“Are you okay?”

“Call me.”

“This isn’t funny.”

“Vanessa, this is incredibly selfish. I have the Tokyo trip in three days. We have things to discuss.”

Mom:

“Greg called. I told him I don’t know where you are because I don’t. I love you. Call me when you can.”

Patricia:

“Vanessa, dear, Gregory is very worried. Please be reasonable and come home so we can talk about this as a family.”

Amanda: nothing directly.

On social media, Amanda posted an Instagram story two weeks later with a boomerang of clinking glasses and the caption, “Family is everything. You can’t choose who stays and who goes.” Heart emojis poured in.

I didn’t respond to any of it.

Instead, I drove west.

Seattle greeted me with a gray sky and steady drizzle, the kind of rain that felt like it might last forever. Olivia had found a furnished month-to-month studio in her neighborhood—a small place with creaky floors, bay windows, and a kitchen that could generously be called “efficient.” The landlord didn’t ask many questions as long as the rent cleared.

“The building’s kind of old,” Olivia said, lugging one of my boxes up the stairs. “But the location is great, and the coffee shop on the corner does the best cold brew in the city. And look, you can see a sliver of the water from the window if you lean this way.”

I stood in the middle of the little studio while rain tapped the glass and felt… safe.

After the sprawling suburban house I’d shared with Gregory, this space should’ve felt cramped. Instead, it felt like a cocoon. No family portraits I didn’t belong in. No furniture chosen to impress clients. No expectations.

“This is perfect,” I said, running my hand along the scratched kitchen counter. “It’s mine.”

The first week in Seattle was all logistics. New bank account at a local credit union. New phone number with a 206 area code. A P.O. box so I didn’t have to share my address with anyone until I was ready. I set up mail forwarding through Jessica’s apartment so nothing from Massachusetts came straight to me.

I emailed my existing clients from my personal account.

“I’m relocating to the West Coast,” I wrote. “If you’d like to continue working together, I can offer a discounted rate for the transition while I reestablish my business.”

A few responded with warmth and support. A few ghosted. That was okay.

Then, because I could feel seven years of swallowing things pressing up against my throat, I found a therapist. Her name was Dr. Lewis, and her office smelled like citrus and had a framed print above the couch that said, “You are allowed to be both a masterpiece and a work in progress.”

Our first session, I told her the story in broad strokes. The marriage, the family, the barbecue, the hot dog, the “challenge accepted.”

“That comment at the barbecue wasn’t the cause,” she said after a while, tapping her pen on her notebook. “It was the final straw. What do you think the first straw was?”

No one had ever asked me that.

I sat there with my hands wrapped around a mug of tea and thought about the first time Patricia had called my business “your little design thing.” The first time Richard corrected me in front of a client. The first time Amanda “jokingly” suggested I dress more like Patricia if I wanted to be taken seriously.

We didn’t solve anything that day. But we named things. And naming is a kind of power.

By the second month, I had three steady clients from the freelance platforms: an author self-publishing e-books, a yoga instructor needing social media templates, a local pet store wanting a new logo. None of it was glamorous, but when I sent invoices and saw payments hit my account—$1,200 here, $750 there—it felt like oxygen.

Then, one rainy Tuesday, I ducked into a neighborhood coffee shop to work because the walls of the studio were starting to feel a little too close.

The place was all exposed brick and mismatched chairs, with a mural of swirling blues and oranges covering one wall. I stood staring at it while the barista made my latte.

“Beautiful, right?” she said, following my gaze. “The owner commissioned it from a local artist. She’s actually looking for someone to redo our menu boards and flyers. Our current ones look like a ransom note.”

“Do you have her card?” I asked before I could second-guess myself.

An hour later, I was sitting at a back table with Eleanor, the owner—a woman in her early fifties with silver-streaked hair, paint on her jeans, and laugh lines that suggested she’d earned every one.

“I don’t care about your resume,” she said, waving off the polished PDF I’d prepared. “Show me the work you do for yourself. The stuff you make because you can’t not make it.”

I hesitated. That folder was dusty. It held pieces I’d done back in college or in the early years of my marriage, before I started watering myself down to fit the Caldwell aesthetic. Bold colors. Risky compositions. Hand-lettered typography that had taken hours.

I pulled them up anyway.

Eleanor studied each piece in silence, occasionally zooming in.

“You’ve been hiding,” she said finally, looking up with sharp blue eyes. “These are good. Really good. But they aren’t recent, are they?”

“No,” I admitted. “I haven’t done work that feels like this in a long time.”

“Why not?”

“Because somewhere along the way, I started designing to impress my husband’s family instead of myself,” I said, surprising myself with my own bluntness. “And they were never going to be impressed, so I just… stopped trying.”

She nodded slowly.

“Okay. Here’s my offer,” she said. “I’ll pay you to redo the menus, loyalty cards, and some promo posters. Fair rate. But there’s one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“You make one personal piece a week. Something just for you. Bring it when we meet. I don’t care if it’s great or if it sucks. I care that you’re doing it.”

I laughed. “That’s not how clients usually work.”

“I’m not usual,” she said. “Do we have a deal?”

We did.

Eleanor became more than a client. She became a mentor, the kind of older woman I wish I’d had around when I first married into the Caldwells. She didn’t sugarcoat things. When a design wasn’t working, she said so, clearly and without malice. When it was good, she didn’t overpraise; she just said, “There. That’s you.”

Week by week, the folder of “just for me” projects grew. Hand-drawn typography pieces. Abstract patterns inspired by rain on the studio window. A reimagined version of my grandmother’s strawberry shortcake recipe, illustrated like a mid-century cookbook page, which made Eleanor say, “Frame that. It’s a piece of you.”

While my new life expanded, my old one slowly receded.

Four months after I left, the divorce papers arrived via my lawyer. Gregory had hired one too. We went back and forth over email about house equity, retirement accounts, who kept which car. It was surprisingly civil. He didn’t fight me on the money I’d already taken. I didn’t ask for alimony.

I had only one personal request: I wanted to keep my original engagement ring—the simple gold band with my grandmother’s stone that Gregory had replaced when his parents suggested he “upgrade” it. He agreed to that without argument.

His only personal note, passed through our attorneys, said, “I still don’t fully understand, but I won’t stand in your way.”

I cried for that one. Not because I wanted him back, but because it was the first time he’d acknowledged that there were parts of our marriage he hadn’t seen.

By month six, I’d picked up a branding project for a local artisan food company—Rainier Artisan Foods—that ended up being a bigger deal than I realized at first. The campaign for their product line—packaging, website, social media—was featured in three small industry publications. It wasn’t front-page news or anything, but it was real recognition, with my name on it.

One night, out of morbid curiosity, I logged into social media with the burner account I’d created after leaving.

Gregory’s profile showed him at a company event, arm around a blonde woman I didn’t know. The caption read, “Grateful for our amazing team.” Amanda had posted a photo from a family dinner at the Caldwell house: long table, perfect place settings, everyone smiling. Her caption said, “Missing no one.”

It stung for about thirty seconds. Then the strangest thing happened: relief.

She’d been right, in a twisted way. When I disappeared, their world kept spinning. No one fell apart. No one collapsed. They’d slotted someone else into the empty chair.

For the first time, it felt less like a tragedy and more like confirmation that leaving had been the only way to find out who I was without them.

Exactly fifty-two weeks after Amanda said those words at the barbecue, I got an email that made my stomach drop.

Subject line: Seeking designer for national campaign.

Sender: Westwood Creative Agency.

I assumed it was spam. It wasn’t.

“Your work for Rainier Artisan Foods caught our attention,” the email read. “We’re developing a new packaging and brand identity for Sheffield Consumer Brands’ organic line and believe your aesthetic would be a strong fit. Would you be available for an initial meeting next week?”

Sheffield Consumer Brands.

The name tickled the back of my brain until I remembered why: it was a subsidiary of Caldwell Marketing Group. One of Richard’s clients.

Of course it was.

I stared at the email for a long time, then called Eleanor.

“It could be totally legit,” she said. “You did good work on Rainier. People noticed.”

“But the timing,” I said. “And the connection. And the fact that it’s exactly one year to the week.”

“Life has a dark sense of humor sometimes,” she said. “Here’s the real question: if I told you this project had nothing to do with the Caldwells, would you want it?”

“Yes,” I said immediately. The budget alone was staggering—more than $19,500 for the initial phase, with the potential for more if it went well. It would bump my yearly income into a new bracket.

“Then negotiate hard, get everything in writing, and do the work,” she said. “Don’t build your new life around avoiding the old one. That’s just another kind of prison.”

I requested more details from Westwood. The creative director, Thomas, sent over a project brief, timeline, and budget that made my inner spreadsheet nerd hum with excitement. There was no mention of Caldwell Marketing Group in any of the documents. Just Sheffield. Just the product line. Just the work.

After three days of going back and forth with my therapist, my accountant, and the part of myself that still flinched at the word Caldwell, I said yes.

We spent three weeks neck-deep in research and concepts. I worked late at the shared studio, building mood boards, sketching packaging layouts, testing color palettes. Thomas was the kind of creative director I’d only ever seen in movies—demanding but fair, blunt but not cruel. When he said, “This is strong,” I believed him.

When he said, “This feels safe; push it,” I pushed.

Our first presentation to Sheffield’s internal team went better than I could’ve dreamed. They liked the direction. They liked the story behind it. They liked the way it made their products feel premium but accessible.

Then came the announcement: Sheffield’s new line would be unveiled at a big industry event in Seattle—the annual Marketing Innovation Gala. As the lead designer, my presence was “highly encouraged.”

The Caldwells always attended that gala. Richard considered it a hunting ground.

At my next therapy session, Dr. Lewis laid out my options.

“You can decline and risk limiting your professional growth,” she said. “You can attend, try to avoid them, and spend the entire night tense and on the lookout. Or you can attend knowing they’ll probably be there and decide in advance who you want to be in that room.”

“Who I used to be in those rooms was Gregory’s wife trying not to say the wrong thing,” I said.

“Who are you now?” she asked.

I thought about the studio space with my name on the door. The invoices I sent. The strawberry shortcake illustration framed above my desk. The first time a client introduced me as “our designer, Vanessa,” with pride in their voice.

“I’m someone who walks into that room because she earned the right to be there,” I said slowly, “not because she came on someone’s arm.”

“Then shop for a jumpsuit instead of a dress,” she said, smiling. “You seem more like a jumpsuit person now.”

I laughed. She wasn’t wrong.

The night of the gala, I stood in front of the hotel mirror adjusting the emerald green jumpsuit I’d picked after three different shopping trips. It was sleek, with a neckline that made me feel powerful instead of exposed, and pockets deep enough to hide my trembling hands if I needed to.

My hair was shorter now, cut into a sharp bob with caramel highlights that caught the light when I turned my head. My makeup was understated, more “I know what I’m doing” than “please like me.” The shoes, a pair of black heels I’d splurged on with part of my Sheffield advance, added three inches and a surprising amount of backbone.

I pinned the event badge with my name and “Lead Designer” under it to my lapel and took a breath.

“You ready?” I asked the woman in the mirror.

She looked back at me steadily.

The hotel ballroom was all gold light and polished wood, the kind of place where deals are made over foie gras and champagne. I checked in, accepted a flute of sparkling wine from a passing server, and found Thomas near a display of the new packaging prototypes.

“There she is,” he said. “The woman of the hour.”

“Just don’t let me trip on the way to the stage,” I said.

“You’ll be fine. Your work speaks for itself.”

As we talked, people drifted over—other designers, marketing directors, executives. I handed out business cards and answered questions about our process. For the first forty minutes, I was just another professional at an industry event. No baggage. No history.

Then the energy in the room shifted, the way it does when someone important arrives. Conversations quieted, then rose again with new energy. I didn’t need to turn around to know.

Still, I did.

Richard and Patricia stood near the entrance, framed by the ballroom doors. Richard looked older than the last time I’d seen him—more lines around his eyes, more gray at his temples—but his posture was the same, chest out, handshake firm, laugh booming. Patricia was immaculate in a navy gown, hair in a perfect chignon, diamond earrings catching the light.

Gregory followed a step behind them, wearing a tailored suit that had probably cost as much as my first car. He looked thinner, more tired. There was a tightness around his mouth I didn’t recognize.

Our eyes met across the room.

For a heartbeat, everything else dropped away.

His eyes widened. His mouth parted like he might say my name out loud, even though we were too far apart for me to hear it.

I held his gaze, let him see that I saw him, that I wasn’t hiding. Then I turned back to the group I was standing with and said, “Sorry, you were asking about lead time?”

When I stepped away to refresh my drink, Richard intercepted me by the bar, a glass of bourbon in his hand.

“Vanessa,” he said. “This is… unexpected.”

“Richard,” I said, nodding. “I’m the lead designer on the Sheffield rebrand. I’m working with Westwood.”

He blinked.

“I hadn’t realized,” he said. “Sheffield went through the agency. We only handle their broader strategy.”

“Westwood brought me in after the Rainier campaign,” I said. “They liked my work.”

His eyes flicked over my jumpsuit, the badge, the prototypes on the display table.

“I see that your work has evolved since you…” he paused, searching for a polite word, “…left.”

“Not evolved,” I said. “Got back to where it was supposed to be.”

He seemed unsure what to do with that.

“Patricia is here,” he said finally. “I’m sure she’d like to say hello.”

“I’m sure she will,” I said, and let him walk away.

Thomas joined me just then, oblivious to the tension.

“Ready for the presentation?” he asked.

“I’ve done harder things this year,” I said.

He grinned. “That’s what I like to hear.”

Amanda appeared five minutes before our presentation was scheduled to start, cutting across the room like a knife in a silk dress. She’d always known how to move in these spaces, to create tiny gravitational fields around herself wherever she stood.

“Vanessa,” she said when she reached us, her smile tight enough to crack. “No one mentioned you were involved in this project.”

“Westwood contracted me,” I said. “Amanda, this is Thomas, the creative director. Thomas, this is Amanda Caldwell.”

“Nice to meet you,” Thomas said, shaking her hand. “Vanessa’s been a rock star on this.”

“We’re family,” Amanda said, the word sharp. “Or were.”

“How nice,” Thomas said, neutral. “Excuse us, we’ve got to get in place.”

On stage, with the lights in my eyes and a microphone in my hand, I felt… oddly calm. I walked the audience through our design choices, how we’d used color and layout to signal “organic but trustworthy,” how we’d built in little digital Easter eggs for customers to discover with their phones. I talked about the research, the testing, the story we were telling with shapes and type.

When I finished, there were questions, then applause. Real applause. The kind that comes from people who don’t know you personally but recognize the work.

From the stage, I could see the Caldwell table. Patricia’s expression was polite, inscrutable. Richard nodded as I mentioned market share projections. Amanda whispered something to the person next to her, face unreadable. Gregory watched me like he’d never seen me before.

Afterward, people swarmed the stage to shake hands and ask follow-up questions. It was a little dizzying, but in a good way. I answered everything I could, promised to email what I couldn’t.

By the time the crowd thinned, my feet ached and my cheeks hurt from smiling. I was gathering my laptop and notes when Gregory finally made his way over.

“You look… well,” he said, shoving his hands into his pockets.

“Thank you,” I said. “You too.”

“I didn’t know you were in Seattle,” he said.

“That was intentional,” I said.

He nodded. “Your presentation was impressive. You always were talented.”

“I always am talented,” I corrected gently.

He winced, but in a way that suggested he agreed.

“I’ve thought a lot about the barbecue,” he said. “About what Amanda said. About how I laughed.”

“So have I,” I said.

“At the time, I told myself it was just a joke,” he said. “But… if a joke makes someone feel that small, it stops being funny.”

“That’s one way to put it,” I said.

“I’ve been in therapy,” he blurted, like he needed me to know. “For about ten months. Dad thinks it’s ridiculous, but… it’s helped.”

“I’m glad,” I said, and I meant it.

“I didn’t stand up for you,” he continued. “Not that day. Not when Mom minimized your work. Not when Amanda needled you. I just let it happen because it was easier than making waves.”

“I know,” I said. There was no venom left in it, just acceptance.

“I miss you,” he said quietly.

The words landed like pebbles on the surface of a lake I’d already crossed.

“I’m glad you’re doing the work,” I said. “I am too. But the person I am now… she can’t go back.”

He swallowed, then nodded. “I figured. I just—” He stopped, searching for something that wouldn’t sound like begging. “Thank you for talking to me at all.”

“I can spare half an hour tomorrow for coffee,” I said. “Professional courtesy. We’re in the same industry now.”

He huffed a laugh. “Professional courtesy. Got it.”

Patricia appeared at his elbow, social smile locked in place.

“Vanessa, darling,” she said. “What an absolute delight to see you. We’ve all missed you so much at family gatherings. No one makes strawberry shortcake like you do.”

There it was—the platter again, pulled from the pantry of my memory.

“That’s interesting,” I said. “Last summer, my shortcake ended up in the pantry while Amanda’s tiramisu took center stage.”

Patricia’s smile faltered for a heartbeat before snapping back into place.

“Oh, that was just a misunderstanding,” she said.

“Seven years of simple misunderstandings,” I said lightly. “It’s funny how easily those add up.”

Before she could respond, the event coordinator called everyone to dinner.

“I need to sit with my team,” I said. “Enjoy the salmon. I hear it’s excellent.”

I left them standing there and crossed the room to the Westwood table, sliding into the seat between Thomas and a woman from Sheffield who kept saying, “We’re so lucky we found you.”

It was only later, in my hotel room with my shoes kicked off and my badge tossed on the dresser, that it hit me just how far I’d come.

A year earlier, I’d been the woman raising a hot dog in mock toast to hide how shattered she was. Tonight, I’d stood on a stage, my name on the screen, my work on the products, my voice steady. The same family who once made me feel invisible had watched me be seen by a room full of strangers for something only I could do.

That was the real “challenge accepted.”

The workshop the next day was smaller, more practical. We spent the morning in breakout sessions about implementation, digital strategy, rollout timelines. I did a segment on integrating packaging with social media campaigns and loyalty apps, and it went smoothly enough that people actually took notes.

During the coffee break, I stepped outside to the hotel’s little courtyard garden to breathe for five minutes. The air was cool, scented with damp soil and whatever flowers the hotel’s landscaper favored.

Patricia found me there. Of course she did.

“You always did know how to slip away from a crowd,” she said, sitting on the bench beside me as if we’d planned to meet.

“I prefer to call it recharging,” I said.

She studied me for a long moment.

“You’ve changed,” she said.

“I’ve reverted,” I said. “To who I was before I tried to fit into a mold that was never made for me.”

She exhaled slowly.

“Families like ours can be… difficult to navigate,” she said. “There are expectations, traditions, ways things are just done. Not everyone understands.”

“I understood,” I said. “I just stopped agreeing.”

“Perhaps we weren’t as welcoming as we could have been,” she said. For Patricia, that was practically a confession. “But you disappearing like that—don’t you think that was a bit dramatic?”

“I left a detailed letter,” I said. “I made sure the bills were paid. I took exactly half of what was ours. I didn’t smash any dishes on the way out. That wasn’t drama. That was a boundary.”

“Gregory was devastated,” she said.

“Gregory was inconvenienced,” I said quietly. “There’s a difference.”

Her eyes flashed. “You have no idea what this past year has been like for him. For any of us.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Just like you had no idea what the previous seven years were like for me. But playing ‘who suffered more’ isn’t a game I’m interested in.”

For once, she didn’t have a ready reply.

“I’m here,” I continued, “because I’m good at what I do and Sheffield needed that. You’re here because Richard is good at what he does and Sheffield needed that. Everything else is… extra.”

She looked at me differently then, like she was finally seeing the lines of my face, not just the role she’d cast me in.

“You always were stubborn,” she said.

“I prefer ‘determined,’” I replied.

On the way back inside, she asked, almost casually, “Will you be at the closing dinner tonight?”

“Yes,” I said. “Westwood has a table.”

“The salmon is usually very good at these things,” she said.

For some reason, that normal, nothing sentence felt stranger than anything else.

Later that afternoon, Gregory and I finally had the coffee we’d half-promised the night before. We sat in a small seating area off the lobby, both holding paper cups, both looking like two people on a first date and a last one at the same time.

“Seattle suits you,” he said.

“It does,” I agreed. “People here don’t care who your father-in-law is. They just care if you do good work.”

“I’m starting to understand how much I expected you to just… adapt,” he said. “To my family. To my schedule. To my dad’s expectations. To Amanda’s moods.”

“You did,” I said. It wasn’t an accusation, just a fact.

“My therapist keeps talking about systems,” he said. “How my family operates like a machine that pulls everyone into their assigned role. I never questioned it because I didn’t have to. You did. You were the only one who truly challenged it—and we treated you like the problem.”

“That’s a lot for you to admit,” I said.

He shrugged, eyes on the coffee lid.

“When you left, I kept thinking you’d come back once you cooled down,” he said. “And when you didn’t, I had to sit with the possibility that maybe we were the ones who needed to change. Not just you.”

“Have you?” I asked.

“I’m trying,” he said. “I turned down a promotion that would’ve tied me even tighter to Dad’s firm. I’m teaching a small business marketing course at the community college. Mom thinks it’s a waste of time. I like it.”

“That’s good,” I said. And it was.

“Is there any chance… not right away, but someday…” He trailed off.

Of course he would ask. We were two reasonably good people who had hurt each other in ways neither of us fully understood at the time. That question was inevitable.

“I think we both needed to become different people,” I said slowly. “And I like who I’m becoming now. I don’t want to risk disappearing again.”

He nodded, tears brightening his eyes but not falling.

“You were always stronger than I gave you credit for,” he said.

“We both were,” I said. “We just needed different circumstances to see it.”

We ended with a hug that felt like closing a book, not ripping out a chapter.

The last Caldwell conversation of the conference happened with Amanda, of course.

She caught me alone in the conference room as I was packing up my laptop.

“I need to ask you something,” she said, arms crossed. “And I’d appreciate an honest answer.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Did you take this project because it was connected to our family? Was this your big comeback move?”

“No,” I said. “I said yes because it was good work at a fair rate with a reputable agency. I found out about the Caldwell connection after I’d already signed the contract.”

“You didn’t think about recusing yourself?” she asked.

“Why would I?” I said. “I’m extremely good at what I do, Amanda. Sheffield needed what I offer. The fact that your family’s company might benefit indirectly is incidental. You’re not the center of my life anymore.”

Her jaw tightened.

“I just find it hard to believe that exactly a year after you vanished, you reappear tied to one of our accounts and it’s all a coincidence,” she said.

“I know it’s hard to imagine, but you’re not the main character in my story,” I said. “Here’s the alternative explanation: I spent a year rebuilding my life, reconnecting with my work, and putting myself in places where good opportunities could find me. This project is one of those. That’s it.”

“At the barbecue,” she said after a moment, voice quieter, “when I made that comment… I didn’t think you’d actually leave.”

“It wasn’t just that comment,” I said. “It was seven years of being told in a hundred ways that I was optional. You just finally said it out loud.”

“I wasn’t saying you were optional,” she protested weakly. “I was saying the conversation was boring.”

“Same message, different packaging,” I said. “But here’s the thing: in your family’s context, I was dispensable. I get that now. What I needed was to find contexts where I’m not.”

She looked unsettled, like no one had ever told her she wasn’t the gravitational center before.

“Greg hasn’t been the same since you left,” she said finally.

“He’s figuring out who he is outside your system,” I said. “That’s a good thing.”

“There’s no chance of you two…?” She gestured vaguely.

“We found closure,” I said. “That’s the only reconciliation we need.”

She nodded once, then turned to go. At the door, she paused.

“Your work on this campaign is good,” she said without looking back. “I would’ve said that even if I’d never met you.”

“Thank you,” I said. And I meant that, too.

The closing dinner that night felt like the end of a long, strange play. The Westwood table toasted our successful launch. The Sheffield execs talked about early buzz. Across the room, the Caldwells held court at their own table, but when someone introduced me to Richard as “the designer behind that amazing packaging,” he didn’t flinch. He just nodded and said, “Yes, she did a fine job,” like we were simply colleagues.

When Amanda gave a short presentation on upcoming marketing trends and included one of my designs on a slide—with my name in small text at the bottom—I felt something inside click into a new place. Not forgiveness, exactly. Not friendship. Just balance.

After the conference, life settled into a new rhythm.

The Sheffield campaign officially launched three weeks later. Early numbers were good; sales up, positive social media chatter, a few blog features praising the look of the new line. Westwood already hinted at wanting to keep me on for another national project.

Eleanor and I sat in our corner table at her coffee shop, rain tapping the windows.

“So,” she said, topping off my mug from the pot on the table, “from family outsider to sought-after designer on a national campaign. Not bad for one year.”

“It feels… satisfying,” I said.

“And the Caldwell aspect?” she asked.

“Professionally cordial,” I said. “Their marketing director emailed me about possibly collaborating through the proper channels in the future. I haven’t decided yet.”

“That’s quite the shift,” she said. “From ‘you’re lucky we tolerate you’ to ‘could we please use your brain for our projects.’”

“Life is weird,” I said.

My therapy sessions with Dr. Lewis dropped from weekly to bi-weekly, then settled into a steady beat—check-ins, course corrections, deeper dives into patterns I didn’t want repeating in future relationships.

“People talk about healing like it’s going back to how you were before,” she said once. “It’s not. It’s becoming someone new who remembers what happened but isn’t defined by it.”

I thought about that a lot. I wasn’t trying to be college Vanessa again. I was becoming this version—one who knew her breaking point and her worth.

Jessica flew out for a long weekend and walked through my studio space with tears in her eyes.

“You laugh differently now,” she said as we watched the sunset from a little overlook.

“How do you even remember how I laughed before?” I asked.

“It was always a little tight,” she said. “Like you were checking if it was okay to find something funny. Now it comes from, like, your whole body. It’s nice.”

Little by little, my life filled with people and things that saw me clearly. The community garden plot I shared with Olivia. The group of designers at the studio who argued passionately about fonts and then went for tacos. My clients who emailed variations of “we trust you; do what you think is best.”

And then, strangely, there was Charlotte.

She reached out via email one day, very professional.

“Hi Vanessa, I’m working with a pediatric clinic on some educational materials and wondered if you’d be open to discussing a design project. Best, Charlotte.”

We met for coffee. We talked about the project for ten minutes and about the Caldwells for two hours. She’d felt the freezing edge of Patricia’s perfectionism and the sharp sting of Amanda’s “jokes” her fair share, too.

“Amanda’s actually taking parenting classes,” she said once, stirring sugar into her latte. “She’s pregnant. She says she doesn’t want to repeat certain patterns.”

“That’s… unexpected,” I said.

“Your leaving shook things,” Charlotte said. “They’d never seen anyone step entirely outside the machine before. It made them look at the gears.”

I didn’t take credit for that. Their evolution was their business. Mine was my own.

One Saturday morning a few months later, I was at the farmers market near my new house—a small place by the water I’d bought with my own money, closing costs and all. It wasn’t big, but it had light and a little backyard and a kitchen that felt like it wanted to be cooked in.

I was choosing tomatoes when I heard my name.

“Vanessa?”

I turned. Amanda stood a few feet away, holding a canvas tote bag with fresh flowers peeking out. Her belly showed under her linen shirt, a clear curve.

“I didn’t know you shopped here,” she said.

“Every Saturday,” I said. “They have the best heirloom tomatoes.”

We did the small talk dance for a minute—the weather, how busy the city felt in summer, the upcoming launch numbers for Sheffield. Then she surprised me.

“I’ve been thinking about what you said at the conference,” she said, shifting her bag on her shoulder. “About being dispensable in some contexts and valued in others.”

“Okay,” I said.

“In these parenting classes, they talk about patterns we learned growing up,” she said. “How we pass them on without meaning to. I’ve realized there were times… a lot of times… when the way our family treated people made them feel like they had to shrink or disappear to keep the peace.”

“That tracks,” I said.

“I don’t want my child to feel like they have to disappear to be seen,” she said, her hand unconsciously resting on her stomach.

“That’s a good starting point,” I said.

We didn’t hug. We didn’t make plans. We just shared that small, honest truth in the middle of a bustling market, then moved on with our respective Saturdays.

On the way home, tote bag digging into my shoulder, I realized that I felt… fine. No adrenaline spike. No lingering anger. Just a kind of quiet clarity.

Back in my little kitchen, sunlight slanting through the window, I unpacked the tomatoes, the cream, the berries. I pulled my grandmother’s chipped white platter from the cabinet. The same one that had sat invisible in the Caldwell pantry.

I made strawberry shortcake from scratch, just like she taught me. Biscuits golden, whipped cream soft, berries glossy and sweet. I plated it carefully, set it on the table, and took a picture to send to Olivia.

“Guess what’s back in rotation,” I texted with the photo.

“That platter is officially a main character now,” she replied.

I set a slice on a plate, sat at my own table in my own house, and took the first bite.

It tasted like every version of me that had survived to that moment—all the times I’d swallowed words at someone else’s table, all the nights I’d stared at the ceiling wondering if I was crazy, all the miles I’d driven with my entire life in the back of my car.

It tasted like being visible to myself.

Later that night, I opened my laptop and stared at the blank page of my journal for a while, then started typing.

Sometimes, I wrote, it takes one cruel sentence at a picnic table for you to realize you’ve been living your life as a supporting character. Sometimes, someone says, “If you disappeared tomorrow, no one would even notice,” and you find out they’re half right. The people who never really saw you don’t notice. But the version of you that’s been buried under their expectations notices so loudly she refuses to stay buried.

Sometimes disappearing from someone else’s story is the only way to appear in your own.

I thought about the hot dog at the barbecue, the tiny flag toothpick sticking out like an accusation. I thought about the way my hand hadn’t shaken when I said, “Challenge accepted.” I thought about the woman in the hotel mirror before the gala, pinning on a name badge with her own name and title. I thought about the strawberry shortcake platter on my kitchen table, finally at the center instead of in the pantry.

The opposite of disappearing, I realized, isn’t being noticed by the people who were always determined to overlook you. It’s becoming so fully present in your own life that their attention stops being the point.

When I finished writing, I sat back and let out a breath I felt like I’d been holding since that day in the Caldwells’ backyard.

Then, because old habits die hard and new ones need practice, I opened the tab for the storytelling channel I sometimes watched—people reading aloud strangers’ stories from online: messy families, petty bosses, small victories. I’d sent them my story in pieces over the past few weeks, anonymized, names changed.

“Have you ever had a moment when someone’s casual cruelty became the catalyst for you to change your entire life?” the narrator’s voice said through my speakers, beginning the video. “Today’s story is about a woman whose sister-in-law told her no one would notice if she disappeared—and how she decided to prove her wrong.”

I listened to my own life told back to me like it belonged to someone else, to the comments rolling in from strangers saying, “You did the right thing,” “I’m proud of you even though I don’t know you,” “I needed to hear this.”

It was oddly healing. Not because I needed validation, but because it reminded me that stories like mine weren’t unique. Everyone was walking around with some version of a hot dog raised in defiance, some version of a car packed at dawn, some version of a strawberry shortcake they’d once hidden in a pantry.

The video ended with the usual sign-off.

“If you enjoyed this story, feel free to share it,” the narrator said. “And if it stirred up something in you—maybe a memory or a question—that’s okay. That’s what stories do. Take care of yourself. You deserve to be the main character in your own life.”

I closed the laptop, turned off the kitchen light, and stood for a moment at the window, looking out at the dark water in the distance.

I thought about the woman I’d been a year before, sitting at a picnic table under a string of patriotic bunting, holding a hot dog with a tiny flag in it while laughter rolled over her like a wave. I thought about the woman I was now, standing barefoot in her own home, full from her own shortcake, her own work hanging on her own walls.

The challenge had been met, and then some.

No one could say I disappeared.

I finally showed up.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load