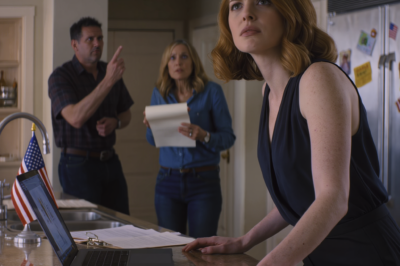

The hallway behind the glass ballroom was bright enough to sting, a corridor of stainless-steel doors and stacked crates where a tiny U.S. flag magnet on a catering fridge twitched with each blast from the vent. The air smelled like lilies and bleach. Beyond the double doors the DJ tested a mic—one, two—then bled a bar of Sinatra as someone laughed too loudly and someone else shushed them. My mother adjusted her pearls. My father looked away. I tightened my grip on the small silver gift I’d wrapped the night before, smoothed my wine‑colored dress, and chose silence, the kind you set down like a card on the table and refuse to pick back up.

I told myself a promise as plain as winter sky: if they pushed me outside the room, I would let the truth walk in.

I stood and let a slice of Vermont air knife the heat from my face. Five minutes later, the chandeliers went quiet and a scream cut the room in half.

Edges cut.

I hadn’t planned to measure the day by edges—the frame of a doorway, the rim of a crystal bowl, the thin metal lip of a trash can—yet there I was, assigned to a folding table beside the service door as if my invitation were a clerical error or a joke. “Hallway seating,” the coordinator said, tapping a clipboard whose corners were softened from years of weddings. “You’re Ms. Hayes?” she asked. “Yes.” Her polite smile faltered only when she found my name, then recovered like it hadn’t. “Right over here.”

Right over here was a draft that licked my ankles each time the service door swung open. Inside the glass ballroom the lake threw back the chandelier light until everything looked lacquered: orchids arched over crystal, candles floated in bowls, flatware winked in lines precise as equations. Twenty‑nine centerpieces marched down the room like soldiers of taste. The resort brochure had bragged about European charm; I could see why my sister had chosen it. People took photos here to prove they’d been invited. My seat, apparently, was a vantage point for the loading bay.

Three hours earlier I’d left Boston under a sky that promised nothing but held—the way skies do in New England—long enough to respect a trip. My mother’s last text had blinked on my dash in the tunnel: Please, Amber. No drama today. It’s Laya’s day. It was the tone you use with a child holding scissors. I drove anyway, repeating gas prices and exit numbers, and told myself I didn’t mind. I knew the smell I’d find when I arrived: lilies and bleach. There’s always a smell when rooms pretend to be perfect.

Growing up, perfection had a sound. It sounded like the clatter of trophies against a shelf and my father’s exhale when the mail came: an acceptance envelope sliding open; an airline itinerary printed in color; applause on a camcorder. “You’re the easy one,” my mother liked to say, gratitude disguised as dismissal. “Independent,” my father added, pride disguised as distance. Both meant the same thing. Invisible is convenient.

I learned that on a Thanksgiving when the house smelled like burnt pie crust and lemon cleaner. Laya was in Portugal with a new boyfriend and the air felt light for once, as if the furniture were finally allowed to unclench. “Grab the old photo album from my vanity,” Mom called. I opened the drawer and instead found a small brown journal, soft at the edges from years of touch. I flipped it open, expecting recipes or lists. Every page began the same way: Laya’s first day of kindergarten. Laya’s favorite meal. Laya’s college acceptance. A whole life cataloged in looping script. Not a line about me. Not my birthdays. Not my name.

“Why?” I asked, the word too clean for what I meant.

My mother smiled like it was a silly question. “You never needed the attention, honey. You were always fine.”

That night I understood there are two kinds of forgotten: being lost and being erased.

Hinges hold more than doors.

Through the glass I watched them pose—my mother in champagne silk, my father straightening his tie, and Laya glowing like a bulb you’d pay extra for. The photographer arranged them by inches and cheekbones. She looked over her shoulder, saw me, and smiled the way people smile at a cashier they’ll never see again. The coordinator intercepted me, a picket fence with a pen behind her ear. “You’re listed for hallway seating,” she said, as if announcing where the sky begins.

I laughed, waiting for her to correct herself. She didn’t. I followed her gesture to the small folding table by the service doors. From there, the ballroom became a diorama—so close I could read lips, so sealed I could not breathe its air. I set my gift on the table and told myself the old lie: It’s fine. You don’t need them. But truth pressed up under my ribs with the patience of something that knows it has time. Maybe I didn’t need them. That didn’t mean they had permission to treat me like I never existed.

The service door hiccuped and banged and hiccuped again. Staff wheeled bins of melting ice past my knees; a busser counted flutes under his breath; a sous‑chef whistled that same Sinatra line every time he pushed through the doors. Each swing gave me a flash of chandeliers glittering like a statement and my mother’s hand on Laya’s shoulder like a crown of approval.

Then the laughter shifted. The photographer’s voice softened to a coaxing murmur that meant make room for the bride, and the crowd obeyed even in their breath. Laya came toward me, bouquet in one hand, veil trailing like smoke. She stopped just short of the threshold and studied me through her reflection in the glass, two versions of her stacked: one adored inside, one cruel outside.

“Well,” she said, tilting her head. “Looks like they finally figured out where you belong.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

She smiled the half‑smile I’d known since childhood, the pre‑theft smile she wore before taking the last word or the last cookie. “Guess you don’t count.” The words landed feather‑soft and blade‑sharp. Guess you don’t count. Like I was an error in math.

For a second my throat went dry—the kind of dry that comes from swallowing pride for years. Behind her, the photographer called, “Bride! We need you back in the shot!” She didn’t move. She wanted noise. She wanted tears. She wanted me to confirm a story she liked telling. I didn’t. I looked at her long enough for the smile to twitch.

“You know,” I said quietly, “there’s always been space for both of us. You’re the one who keeps shrinking it.”

Her eyes narrowed. “Oh please, Amber. Not everything is about you. This is my day. You could at least pretend to be happy for once.”

I let out a small laugh, the sound a tire makes releasing one quiet breath. “You made sure I couldn’t even sit in the same room. What exactly am I celebrating?”

For a moment the mask slipped. Fear flashed, then she lifted her chin. “You always twist things. Maybe Mom was right. You make everything difficult.”

Mom. The name hit harder than I wanted. I saw the brown notebook again, every page a prayer to one daughter.

“I’m not difficult,” I said. “You just don’t like that I see things as they are.”

She rolled her eyes. “You sound just like Dad—pathetic and bitter. Face it, Amber. Nobody needs your approval. Not here. Not ever.” She pivoted, perfume and disdain trailing in a white wake.

I watched the gown swish, felt the burn gather behind my eyes, and recognized it this time: not the old hurt, the clean burn of oxygen in a room that had been shut too long.

The box in my lap was small. The truth inside it wasn’t.

I slid the silver gift into my bag. If they didn’t want me in the room, fine. But I wasn’t leaving empty‑handed. Not this time.

A promise is only a promise if you put it somewhere you can’t ignore it.

Three weeks earlier, I’d run into one of Laya’s former coworkers in a Boston coffee shop, the kind of place that pretends to be indifferent to its own muffins. We said the usual things. The weather. The city. Then she lowered her voice and said the unusual thing. “I shouldn’t tell you this.” She told me anyway. Laya had been bragging for months about a man named Noah—sweet, naive, generous in the ways that made life easy. “A few fake tears and I get the house, the money, the last name,” the coworker repeated, watching my face the way you watch a candle flick before it gutters. She slid her phone across the table. Screenshots. Dates. A photo of a contract on a marble counter with an artfully placed pen. My coffee went cold. I took a breath so careful it felt like a thread.

I didn’t plan to use it. I didn’t plan to do anything except live with the knowledge that my sister had exchanged love for leverage. Then my mother texted me the rule for the day. No drama. Then the coordinator said hallway seating. Then Laya said, Guess you don’t count. That was the arithmetic that tipped.

Now, in the corridor, I retied the ribbon on the silver box with a steadiness that surprised me. I walked to the gift table at the ballroom entrance where a cousin was arranging bows into a rainbow pile, purely decorative currency. The wedding planner fussed with a centerpiece and told someone to dim the sconces two percent. I slid the silver box among the other presents and wrote, in deliberate print, To Laya & Noah. Inside, beneath a crystal frame, lay the folded note and the screenshots. Not a threat. Not even a warning. Just the truth, wrapped like something you’d want to keep.

The U.S. flag magnet on the catering fridge flicked once as the vent kicked on. I checked my reflection in the glass—still composed, even graceful if you didn’t look too closely. The promise I’d made to myself felt settled, not hot. I turned away and walked toward the exit. The Vermont evening hit clean and blue. The lake held the ballroom’s glow like a snow globe, sealed, flawless, unreal.

Let the truth find its way.

On the far side of the glass, the first dance began the way first dances always do—too slow at first, the groom looking for his rhythm, the bride telling him with her hands where to put it. The violinist found the center of the note. Camera flashes stitched gold across the room. From the parking lot I could hear the crowd’s soft cheer thin into a hush.

Then someone at the gift table said, “Open that one.”

A cousin tugged the ribbon free. Paper fell in two neat petals. The lid lifted. A crystal frame winked. Under it, a folded note slid face‑up. Noah’s hand reached before Laya’s. He read. He turned the page. He read again. His lips made a shape like a word he wasn’t ready to say.

The music didn’t stop; it frayed. The violinist missed a beat. The DJ reached for a dial and didn’t know which.

“What is this?” Laya asked, too bright, too loud. “This is someone’s idea of a joke.”

Victoria—his mother—had been watching from across the room with the calm of a storm wall. She stepped close. “I think you should read the rest before you blame anyone,” she said. “These came to me this morning, forwarded from a stylist you hired. Apparently they were in the wrong thread.”

“That’s not possible,” Laya said, the word possible sounding like a window she needed to open right now and couldn’t find the latch to.

“It’s real,” Noah said quietly. “The dates match.” He turned the final page. A photo of a text: The house will be mine by Christmas.

Justice has a sound. Sometimes it is a note a violinist can’t hold.

A gasp rippled the room, but no one wanted to be the first to say it out loud. Phones hovered then rose. The photographer froze with his finger above the shutter, deciding whether to make art or evidence. “Who sent this?” Laya hissed, fingers shaking. “Who—”

A bridesmaid whispered, “Amber Hayes,” like it might be a spell that reversed things if you said it right.

“She didn’t,” Victoria said. “She only told the truth.”

Noah set the papers on the table, the edges aligning to a life he thought he had. He reached inside his jacket and unfolded a document with the patience of a man who had already had the longest day of his life. “This is a petition to annul,” he said. “I already signed it.”

“You can’t,” Laya said, eyes glassed, voice a wire about to snap. “You can’t humiliate me like this.”

“I’m not humiliating you,” he said. “You did that yourself.”

Someone killed the music entirely. The chandeliers hummed to fill the silence. A child asked, “Mom, what’s happening?” and nobody knew how to answer in a way a child could keep.

Crystal shattered when the frame hit the floor.

I had made it to my car by then, engine idling, heat fogging the windshield at its lower corners. The glow from the ballroom windows jittered across the lake. I couldn’t hear words, only the scream when it finally came—sharp, high, echoing. Then a chair tipped with a dull thud. The sound I had not wanted so much as needed, not for revenge but for closure: the sound of a story breaking where it had been bent.

Inside, mascara streaked and vows unspooled faster than anyone could gather them. “You’ll regret this!” Laya shouted, the sentence breaking in the middle like ice.

“No,” Noah said, turning away, shoulders heavy. “Laya, you will.” He walked off the dance floor. Victoria followed, the crowd parting.

My mother stood pale and stiff, champagne shivering in the flute. My father’s mouth was a line that meant stay still or everything inside will fall out. “Do something,” Laya begged them, reaching. “Fix it.”

My father spoke for the first time all night. “You should apologize to your sister.”

The sentence fell like a small bell in a large church. Even my mother looked at him like she’d never heard that sound before.

“Apologize to her?” Laya laughed, brittle and wrong. “She’s not even family.”

“That’s where you’re wrong,” my father said. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to.

By the time the staff arrived with brooms and dustpans to coax crystal off the floor, Laya sat under the chandelier with a bouquet slipping from her wrist, a queen whose crown had always been borrowed. Twenty‑nine centerpieces still glowed as if they didn’t know anything had happened.

I was already gone.

Sometimes the loudest revenge isn’t a scream. It’s the sound of your own footsteps leaving the room.

The parking lot gravel cracked under my heels like punctuation. I didn’t slam the car door. I didn’t peel out. I pulled forward as if I were leaving any party at any hour the air in Vermont turning the world to glass. On the road past the resort’s staff entrance the catering fridge door clicked shut, and that tiny flag magnet trembled in the vent’s breeze, a detail so American and so ordinary it felt like a benediction: you can move on.

The drive back to Boston unspooled in lanes and markers, steadier than my pulse. My phone buzzed in the cup holder as if it were trying to stand up. By the time I crossed the state line, it showed sixteen missed calls from Mom, three from Dad, one from a number I didn’t recognize. I didn’t check any of them. The quiet was worth more than the explanations.

At the apartment my keys sounded too loud. The place smelled faintly of coffee and rain. I hung the wine‑colored dress over a chair and stared at it until the fabric read as armor I hadn’t known I was wearing. The silver ribbon from the gift lay coiled in my bag like a small horizon I’d carried home without meaning to.

A text flashed. Please answer, Amber. We didn’t know. That was my mother. She always said that when knowing would have cost something. I set the phone face‑down on the counter and opened my laptop instead. A map of Maine glowed with tiny coastal towns like beads on a string. I clicked one I couldn’t pronounce and booked a week by the water. It felt like permission.

The balcony air was cleaner than it had any right to be. Across the river a neighbor’s porch flag snapped once and fell still. Morning cut the skyline into gold and shadow. They could keep their apologies, their reasons, their revisions. I had mine now.

For the first time in my life, silence didn’t mean being unseen. It meant being free.

Hinge by hinge, the day had closed behind me. The box had been small. The truth had not.

If you’ve ever been fitted to the edge of a room and told to be grateful for the view, listen: walking away is not surrender. It’s the beginning of your map.

And because stories return to their objects, I will say it once more: I placed a small silver box where everyone could see it; it opened the way doors do in storms; it broke into a thousand shards that caught the light and showed, at last, every face as it really was.

Now they see you.

When the first messages from cousins and aunts and friends who were mostly Laya’s friends began to blink through—Are you okay? What happened? I’m so sorry—I answered none of them. The point of a closed door is not what’s on the other side; it’s that you can close it. I made coffee. I watched steam lift. I didn’t post or screenshot or explain. The lake in Vermont would be smooth again by now. The staff would be sweeping confetti into piles. The invoice for the lighting would hit someone’s inbox—$19,500 due on receipt—and the same hotel that had sold perfection by the hour would move to the next event. Perfection is a business. Truth isn’t. That’s its power.

By afternoon the numbers climbed—voicemails, texts, little dots pulsing as people typed. I let them. I showered and pulled on jeans. I packed a small bag for Maine: sweater, book, shoes that forgive. The ribbon I’d carried home I tied around the handle, a private joke so quiet it might as well be prayer. Before I left I glanced once more at the dress on the chair. It would go to a thrift store next week and live another life. That felt right. Things get to become other things.

On the sidewalk, the city sounded like the city—sirens farther than they sounded, a bus sighing, a dog’s nails clicking a life you only hear when yours isn’t drowning it out. I walked toward the river because moving toward water has always felt like accuracy to me. Halfway there my phone trilled—a sound I usually set to mute—and I almost didn’t look. Noah’s name lit the screen.

I hesitated then answered. “Amber?” His voice was hoarse from a night that had not been kind. “I—thank you. Not for what happened. For the truth. It hurts less than the lie would have.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it.

“I filed the petition last week,” he said. “I was hoping I was wrong. I wasn’t. Today made it easier to do the hard thing.” He exhaled. “My mother wanted to tell you something. I said I would instead: we saw you long before tonight.”

It shouldn’t have made my throat tight, but it did. “Take care of yourself.”

“You too,” he said. “Goodbye.”

Goodbye. The word that sounds like a door with soft hinges.

I walked on. The river flashed between buildings. In a window I caught my reflection and, for once, didn’t flinch at reminding myself I was here. In my bag the ribbon shifted. Somewhere in Vermont a new story was beginning without me. That, too, was part of the point. You don’t have to stay in a story to finish it.

That night, in a motel a mile from the Maine line where the bedspread was too floral and the ice machine made a noise like serious thinking, I turned on a lamp and opened a notebook. Not brown. Not soft from years. Blank and blue and ready. I wrote one sentence: The hallway smelled like lilies and bleach. Then I wrote another. Then I stopped when the words felt like they knew where they were going and didn’t need me to drag them. Outside, a flag on a pole by the office door made a shy sound in the wind.

Morning would come—a mechanic’s light, not an artist’s—and I would cross into Maine and sit by water that didn’t know my name. I would drink coffee from a diner mug and leave a too‑big tip because the waitress would call me honey without asking where I belonged. I would count nothing and belong to everything that didn’t care who I had been yesterday.

At my sister’s wedding, I found my seat by the trash cans. This morning I am seated by a river. Same quiet. Different meaning. Back then it was humiliation. Now it’s peace.

Now they see you. Now you see you. And when those two things finally meet, the room you tried to earn turns out to be a hallway you can walk past without stopping.

Edges cut. So do choices. Choose yours.

The motel at the Maine line had a front office that smelled like pencil shavings and ocean cleaner, a bell on the counter that no one needed to ring because the clerk always looked up. A small U.S. flag leaned in a jar of pens, its edge frayed from a thousand breezes. I paid cash for the first night because it felt like a boundary I could touch, and the clerk slid a key on a blue tag toward me like we were both agreeing to something gentle.

Upstairs, the air shook with the hum of the ice machine and a thermostat set stubbornly to 72°F. I dropped my bag, untied the silver ribbon I’d carried home without meaning to, and looped it around the lamp pull. It swung once, caught the light, and went still.

Distance is a ruler no one else can hold.

The phone on the nightstand kept lighting up and resting and lighting again like a heartbeat trying to find pace. I let it. When I finally turned it over, the screen stacked messages like plates.

Mom: Please answer. We didn’t know.

Dad: Call me when you can.

Unknown: Amber, this is Noah. If this is a bad time, I’ll try tomorrow.

Cousin Bree: Are you okay? It’s all over everywhere.

A bridesmaid whose last name I didn’t know: You didn’t have to do that.

Twenty‑nine missed calls. I thumbed the screen to voicemail and listened to the first two seconds of each until I had heard the tone in all of them—the tone that happens when certainty snaps.

I made coffee in the room’s stubborn little machine, sat on the edge of the bed, and let the first call ring through.

“Amber?” my father said, his voice low, as if the phone were a sleeping dog. “Kiddo, I—how are you?”

“I’m fine,” I said, and for once the word wasn’t a lie.

“I should have… last night I should have said something sooner,” he said. “Your mother—”

“She can call me herself,” I said.

He breathed. “She will. I wanted to tell you first, I’m proud of you. Not for what happened to them. For protecting yourself.”

I looked at the silver ribbon around the lamp pull and remembered the quiet click of the ballroom doors. “Thanks, Dad.”

“Can we get breakfast when you’re back?” he asked. “Charlie’s on Beacon, the place with the too‑thick toast.”

“Maybe,” I said, already tasting the corner of a fried egg. “Text me the time.”

When we hung up, I pressed play on the next voicemail. My mother’s voice had the brittle sweetness of spun sugar. “Amber, it’s me. Please, we need to talk about what happened. Your sister is… this is more serious than you think. People are calling. Victoria posted—just call me. Please.”

More serious than you think. The sentence people use when they want you to carry their weather.

I set the phone face down and opened the notebook I’d bought at a Walgreens on the way up, blue‑lined and ready. I wrote: The lake took the scream and softened it, because water softens everything if you let it. Then I stopped and let the room be a room.

By morning the sky over the motel’s parking lot had the color of a clean plate and gulls were arguing over nothing important. I walked to a diner with a counter that had seen stories and a waitress who called everyone honey because real love is repeatable. The TV above the pie case showed weather and the crawl at the bottom of the screen showed politics and a couple in matching fleece argued, lovingly, about whether to split the pancakes. I ate eggs and checked my phone only because I wanted to tell Noah I’d heard him and heard him clearly.

He answered on the second ring. “Amber.” The way he said my name made me wish Laya had never learned it.

“I’m sorry you had to find out like that,” I said.

“I’m not,” he said. “I mean I wish it hadn’t been public. But the truth is cheaper than the lie would have been. My mother says the same.”

“I didn’t do it for either of you,” I said, and then softened, because kindness is also repeatable. “But I’m glad you’re not stuck in something built on a script.”

He exhaled. “The resort invoiced Laya for lighting—nineteen thousand five hundred, due on receipt. The string quartet deposit was seven thousand nonrefundable. The monogram for the dance floor was twelve hundred. I keep thinking in numbers this morning. Numbers are real.”

“They are,” I said. “That’s why they scare people who like costumes.”

He was quiet a beat. “My lawyer filed the annulment petition yesterday. We’ll get it served this week.”

“Take care of yourself,” I said.

“You too,” he said. “And Amber? The box was… elegant.”

When I hung up I turned my mug so the chipped side wouldn’t face me and watched the flag above the door lift with someone’s exit and fall again when the door shut. The motion felt like a lesson I could use more than once.

At noon my mother called again and I answered because avoidance is a habit, not a destiny.

“Amber?” she said, breathless, as if she had run up a flight of stairs I couldn’t see. “Thank God. We need to fix this.”

“We?” I stirred my coffee, the spoon asking a small silver question against the ceramic. “Or you?”

“Don’t be cruel.”

“I’m being accurate.”

She huffed. “You’ve embarrassed your sister in front of an entire town. People are calling my phone, your aunt is dramatizing on Facebook, Victoria sent me an email like she’s a judge, and your father is—your father is being unhelpful.”

“I didn’t embarrass Laya,” I said. “Her choices did. I wrapped the truth like a gift because this family only opens what’s wrapped.”

“Why didn’t you come to us?” she asked. “We could have handled this quietly, like adults.”

“Like adults who put me next to a trash can?” The sentence came out gentler than it looked. “You were never going to choose me over the picture you wanted.”

She inhaled, held it, exhaled. “You’ve always been so… self‑contained,” she said finally. “I thought that meant you didn’t need… attention.”

“You kept a journal,” I said, before I could talk myself into the easier thing. “Pages and pages about Laya. Not a line about me.”

“That’s not fair,” she said, but there was no force in it. “It was just—”

“Convenient.”

She didn’t answer. When she spoke again her voice had the smallness of a hand on a closed door. “Can I come see you? Today. I’m in Boston.”

“No,” I said, because boundary is a practice that requires practice. “Tomorrow. Public place. Charlie’s on Beacon. Noon.”

“Fine,” she said, and I knew from the word that she had put on lipstick.

We are allowed to script our own apologies.

Back at the motel I folded the ribbon into my wallet as a placeholder for the page I was living. I took a walk toward a strip of beach where the wind could lean and no one minded. A father and daughter flew a kite that did not care whether it was invited. An old man stooped for shells and stood with a sound that meant he was still willing. I breathed and the breath went all the way down. When I turned back toward the motel the sun had slid so far to the left that the shadows had to learn themselves again.

The next day at Charlie’s the toast was still too thick and the coffee still loyal. My mother arrived in a coat that made an announcement and sat on the edge of the booth like she wanted the option to run. She held her purse like a stage prop. I waited.

“Amber,” she said. “You look tired.”

“I slept,” I said. “That’s a new thing.”

She was silent until the waitress poured coffee and called me honey as if I had earned the title. When the waitress left, my mother slid a small brown journal from her purse and set it between us. The edges were soft, the elastic loop tired. My body remembered holding it.

“I brought it,” she said. “I thought… maybe you should see it again.”

“I’ve seen it.”

“Not like this.” She opened to the first blank page. In new ink, careful, she had written: Amber’s first day of everything I didn’t see. Beneath it, dated yesterday, she’d listed a dozen tiny lines that did not read like a performance: The way you hold a cup with two hands when you’re thinking. The way you check a door twice without drama. The way you make room for other people in photos. The way you don’t ask for what you haven’t earned.

She turned the book so it faced me. “I told myself you were easy. That was just… lazy.”

“That word fits,” I said.

She closed her eyes. “I’m sorry.” She opened them. “I am.”

There it was. Not a production, not a plea for me to carry her shame. Just a sentence set down and left to be itself.

A hinge turned.

“Do you want me to forgive you here,” I asked, “or later?”

“I want you to tell me what you need.”

“I need you to stop using my quiet as a trash can,” I said, surprised at my own exactness. “I need you to call things what they are. I need you to stop telling me who I am when it’s inconvenient.”

She nodded like someone had finally handed her the right map. “I can do that.” She looked past me toward the window, where a boy walked by with a flag on his backpack and a dog that refused to be hurried. “Laya says she wants to apologize,” she added, voice uneasy.

“She can write it,” I said. “And then she can let it be true.”

My father arrived late, smelling like the cold air that sits on a tie. He slid into the booth, ordered toast, and looked at the journal like it was a relic he had not been brave enough to read.

“How are you, kiddo?” he asked.

“I’m okay.”

“I should have noticed sooner,” he said. “I kept telling myself that if I stayed quiet, your mother and your sister would… work themselves out. Quiet won’t fix what loud broke.”

We ate like people who had learned something the hard way and wanted to keep it. When the check came my father reached and I let him. He tucked a twenty under the plate for the waitress because some habits are worth teaching twice.

On the sidewalk my mother touched my sleeve. “Come to Sunday dinner,” she said. “No pressure. Just… come if you want.”

“I’ll think about it,” I said, and watched her accept that the word meant what it meant.

Boundaries make room for the right kind of return.

Two days later an envelope slid under my apartment door: cream paper, my name in looping script I recognized from thank‑you cards for gifts I hadn’t gotten. Inside, a letter from Laya on stationery stamped with her new almost‑name.

Amber—

You humiliated me. You always wanted to. You pick moments to make yourself the center. You could have just… not.

The next line had been started twice and scratched out twice. Under it, tiny, like someone had turned down the volume on herself:

I am sorry for the way I spoke to you. I am sorry I made you sit outside. I don’t know how to be anything other than the person I’ve been asked to be. I am trying to learn.

—Laya

I read it twice. The first paragraph was a reflex. The second was a beginning. I set the letter on the counter beside the ribbon and let both sit.

That afternoon Victoria called from a number my phone labeled potential spam because algorithms can’t smell pearls. “Amber,” she said when I answered, “I wanted to thank you personally.”

“You don’t have to.”

“I do,” she said. “I have a son who believes people until they prove him wrong. I’d rather he keep that part. You handed him a map.” She paused. “Also, for what it’s worth, I told your mother last night that if she can’t hold two daughters at once, she should practice with smaller things and work up.”

I laughed, a clean sound. “She brought a journal to lunch. That felt like practice.”

“Good,” she said, and I could hear the ice in her glass answering the word. “Be well.”

Be well. The kind of goodbye that doesn’t ask for a future.

By the end of the week the noise had thinned the way noise does when it realizes it has to live somewhere else. The resort returned a portion of the catering bill; the florist charged full; the quartet kept their deposit; the lighting company emailed a final notice already formatted. Somewhere an aunt still posted paragraphs on Facebook, and somewhere a cousin took screenshots for posterity. I answered no one. I took the train north and watched the marshes flash, their winter blonde like a forgiveness I could live inside.

On Sunday I stood outside my parents’ house with a pie I hadn’t baked and a spine that had learned to stand up without permission. The lawn flag my father insists on replacing every Memorial Day lifted and settled in the mild wind like a breath that had learned how. I rang the bell and heard the thud of feet, the bark of a neighbor’s dog, the clink of silver in a bowl because even in new stories, dishes have to be washed.

My mother opened the door. Her eyes looked like two versions of her had finally agreed on something. “You came,” she said.

“I did,” I said. “On time.”

She stepped back and I walked into the same house I’d left a hundred times and felt my body do none of the old things.

At the table my father had set a chair for me in the middle of one long side—not at the head, not at the corner where I used to hide a knee against a leg. A place. No name card. No choreography. Just a plate and a folded napkin and the sound of a room making room.

Halfway through the meal my mother reached under her chair and lifted a small wrapped box. Silver paper. Ribbon tied too tight, like someone practicing with their hands. She set it by my plate.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“Something I should have given you before you had to give it to yourself,” she said. “Open it later. Or don’t. It’s yours either way.”

I left it on the table until dishes were done and the dishwasher hummed and my father pretended not to cry in the pantry over the recycling. On my way out I tucked it into my bag and hugged my mother for exactly as long as felt true. At the door she said, “We’re trying,” and this time the we included me.

Trying is louder than perfect when you listen right.

On the train home I loosened the ribbon and lifted the lid. Inside lay a photo I had never seen: me at six, on a dock, holding a minnow in two careful hands, my mother crouched behind me with her mouth open mid‑laugh at a joke I must have told. On the back, in yesterday’s ink: Amber’s first day of being seen. Under it, a second line: Not the last.

I tucked the photo into my wallet where the ribbon had been. Objects become symbols when you make them earn it.

In the weeks that followed, life did what life does when you stop trying to audition for it. Work was work. The rent was due on the first. The dry cleaner lost a button and then found one that matched. I went to Maine again and sat by water that did not ask questions. When my mother texted sometimes she sent pictures of small things—steam over soup, frost on the old maple, the dog that wasn’t ours sitting on our porch like it might be. My father called on Saturday mornings from the hardware store to ask whether I needed anything as if loyalty came in sizes.

Laya sent one more letter. No apology this time; not an attack either. A photo of her in sneakers and a sweatshirt, no makeup, no caption, just her face without the lights. Under it a sticky note: I’m in a class. I’m doing the work. I thought you should know. I wrote back two words: Good luck. Then, because growth is a muscle that benefits from reps, I added: Mean it.

On a Thursday that should have been nothing special, I walked past a storefront window and saw a woman in a wine‑colored dress. For a breath I thought the glass was time. Then I realized it was me in a reflection that didn’t flinch. I stopped, checked the door twice the way I do, and smiled at the habit for not needing a reason. In my bag the silver ribbon, now creased, held my place in the notebook where I’d reached a new sentence: The room that tried to make you smaller is not a room; it’s a test.

I bought a small magnet at a corner shop—red, white, blue—and stuck it on my own fridge next to a grocery list that included things I like. Every time the vent kicked on, the magnet trembled like a reminder you could see from across the room: choose your weather.

The story ends where it began because true circles don’t trap; they teach. The hallway smelled like lilies and bleach. The ballroom glittered like a promise that charges by the hour. A small silver box sat where everyone could reach it. A scream echoed because some truths have to leave the body. A life got larger because a woman who had been told to stay small opened a door and walked through it.

Edges cut. So do choices. Choose yours.

Now they see you.

Now you see you.

And when those two lights hit each other just right, the chandeliers don’t have to dim—your own room gets bright enough.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load