I was still holding the little wooden cocktail stick with the tiny American flag on it when the waiter told me my daughter might have tried to hurt me.

The flag had been stuck in a miniature slider on my appetizer plate at L’Orangerie, the most expensive rooftop restaurant in the city, the kind of place where you needed to know someone just to get on the waitlist. Below us, the downtown skyline glowed red, white, and blue from a digital billboard across the street playing a looping Fourth of July ad, even though it was early November. My glass of cabernet sat on crisp white linen, beads of condensation clinging to the stem.

I had just stepped away from the table to take a call from a Swiss private bank confirming that sixty million dollars had finally landed in my account. For the first time since I was twenty-eight, I didn’t technically have a job. I should’ve felt nothing but relief.

Instead, a young waiter with shaking hands blocked my path back to the dining room.

“Mr. Shaw?” he whispered, voice barely cutting through the soft Sinatra playing over the speakers. “I’m sorry, sir, but… I think your daughter just did something weird with your glass.”

That was the moment I found out my only child might have come to my celebration dinner not to toast my life’s work, but to erase me from it.

An hour earlier, if you’d asked me what sixty million dollars feels like, I would’ve told you it doesn’t feel real at all.

Wire transfers don’t have a smell. They don’t sound like anything. There’s no physical weight to them, no crate to lift or pallet to move. They exist as pixels on a screen in an office with too much glass and not enough soul.

I had signed the last set of documents in a conference room overlooking the Bay, my signature looping across the page with the same blue pen I’d used to sign my first lease for a rented garage in Palo Alto forty years ago. Apex Biodine, the little biotech company I started with two grad students and a secondhand centrifuge, was now officially owned by a Swiss holding group with a name that sounded like a Bond villain.

“Congratulations, Mr. Shaw,” the banker had said from Geneva, his voice smooth and detached through the speakerphone. “We can confirm the USD 60,000,000 has cleared. You are a very liquid man.”

I remember looking down at my hands. Calloused knuckles, a faint burn scar across my left thumb from an early lab accident, veins like thin river maps under thinning skin. These were not the hands of a man who thought of himself as “liquid.”

They were the hands of the mailman I’d once been, the lab tech I’d once been, the husband and father I still was.

“You did it, Peter,” my attorney, Harrison Wright, had said quietly as he gathered the closing binders. “You’re officially retired. Go do something irresponsible. Order the most expensive steak in the city.”

So I did.

I called my daughter.

“Dad?” Emily had answered on the second ring, sounding bright and just a little too breathless. “Are we celebrating tonight?”

Her husband, Ryan Ford, was in the background, his laughter drifting through the line. He always sounded like he’d just told a joke only he understood.

“I thought we might,” I said. “L’Orangerie, seven o’clock. My treat.”

“Your treat?” she teased. “Dad, with sixty million dollars, it’s always going to be your treat.”

I laughed, because that’s what she expected. Because I was still the dad who fixed clogged sinks and wrote emergency checks, not the man whose name had just wired around the world.

If there was a promise hanging in the air that afternoon, it was this: I was finally going to live like a man who had something to celebrate, not like the widower who still drove a seven‑year‑old sedan and drank coffee out of a chipped mug.

I just didn’t know the first people I’d have to defend that promise from would be sitting across the table from me, holding their own wineglasses.

The thing about getting old in this country is that people start to look at you like a problem to solve instead of a person to respect.

I’m sixty‑eight. In Silicon Valley terms, that might as well be a hundred and eight. Most of the founders on the covers of magazines are young enough to be my interns. Somewhere around sixty, the way people spoke to me began to tilt. Waiters called me “sir” with that extra softness that really means “fragile.” Young executives at my own company started overexplaining basic concepts, just in case.

Only one person never looked at me like I was slowing down: my wife, Laura.

Laura had been gone three years. Cancer. A quiet word for a loud, ugly disease. We’d bought our little three‑bedroom ranch house on a cul‑de‑sac in Redwood City the same year Apex Biodine moved out of the garage and into its first real building. She’d painted the kitchen herself, yellow like late‑afternoon sunshine. She collected patriotic coffee mugs from thrift stores—mismatched stars and stripes, faded flag decals, bicentennial logos from 1976. Every morning for forty years, she handed me one full of black coffee before I left for the lab.

The morning of the sale, I’d pulled my favorite mug from the cabinet without thinking. White ceramic, tiny American flag on one side, “Made in USA” printed proudly on the bottom, even though the sticker underneath said “China.” I drank my coffee and watched the flag reflected in the kitchen window, rippling with the steam.

Forty years of work. One last cup in that house before everything changed.

Laura used to say that people show you who they are around money and around illness. “Pay attention in hospital rooms and at reading of wills, Peter,” she’d tell me, folding laundry on the couch while some old Sinatra record played in the background. “That’s when the masks slip.”

She’d never trusted Ryan.

The first night Emily brought him over, he arrived with flowers for Laura and an expensive bottle of wine I knew he couldn’t afford from the car he was driving. He called me “sir” and pretended to be impressed that I still kept my old mail carrier’s uniform in the hall closet, framed.

“I love that you started blue‑collar,” he said, flashing perfect teeth. “Real American dream stuff.”

Laura watched him the way she watched complicated puzzles, tilted head, eyes narrowed just a touch.

When they left, I was wiping down the kitchen counters when she spoke.

“He doesn’t see Emily,” she said softly.

I looked up. “What?”

“He sees your last name,” she said. “He sees Apex. He sees the lab, the patents, the future payout. He’s looking at your checkbook, Peter, not your daughter.”

I’d laughed then. I wish I could say I’d listened.

“Laura,” I said, “he’s just ambitious. He loves her. You’re being a little… harsh.”

She didn’t argue. She just went back to folding dish towels, the small lines at the corners of her mouth tightening. That was Laura’s version of shouting.

Grief makes you easy to fool. That’s the part nobody warns you about.

After she died, the house felt wrong. Too quiet, too big, the yellow walls too bright for one man. For a full year, I went through the motions: work, walks around the neighborhood, frozen dinners eaten over the sink. I stayed away from the part of the closet where her clothes still hung.

During that time, the only people who consistently showed up were my employees and my board. My daughter called, but there was a distance in her voice, like she was phoning from another planet. She’d married Ryan; they lived in a brand‑new gated community in Los Gatos, more marble than personality, with a leased Mercedes SUV and a “Live Laugh Love” sign over the kitchen sink.

They came by for holidays. Birthdays. Emergencies.

Like the time Ryan lost twenty thousand dollars on a “sure thing” investment and Emily showed up on my doorstep with mascara streaked down her cheeks.

“Daddy, please, he didn’t mean to,” she’d cried. “We’re going to lose the house.”

I’d written a check without even asking for details, because that’s what fathers do in this country. We plug the leaks. We mop up the messes. We tell ourselves it’s love, not enabling.

That night, Laura’s voice rang in my head through the empty kitchen.

He doesn’t see Emily. He sees a safety net.

By the time rumors of the Apex sale leaked to the financial press six months before closing, my calendar filled up with invitations from my daughter again. Brunch. Golf. “Dad, let us help you with your files. You shouldn’t be handling all this paperwork alone. Ryan knows a lot about transitions.”

They mistook my loneliness for confusion. I mistook their greed for affection.

That was my first real mistake.

The second was letting my guard down at that dinner table.

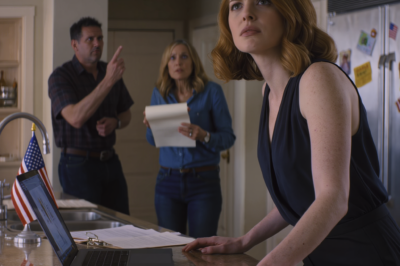

L’Orangerie was the kind of restaurant where the waiters moved like ghosts and the bread had its own tasting notes. Crystal chandeliers reflected off floor‑to‑ceiling windows, the city’s lights scattering like diamonds on the water below. At our table near the glass, a little paper American flag stuck out of my appetizer—a miniature symbol of the dream I’d spent my life building.

Ryan lifted his glass of sparkling water as soon as we sat.

“To you, Dad,” he said, grinning. He’d started calling me “Dad” more often since the acquisition talks began. “To the man who built something from nothing and cashed out bigger than any of us could’ve dreamed.”

He made “nothing” sound like a punchline.

Emily leaned in, her expression bright enough to light the room.

“We’re so proud of you,” she said, reaching across the table to squeeze my hand. The diamond on her left ring finger—my diamond, if we’re being honest—caught the light. “You did it, Daddy. You really did.”

Their words said “proud.” Their eyes said “jackpot.”

I raised my wineglass out of habit, not thirst. “To family,” I said.

That sentence would come back to haunt all three of us.

We ordered. Ryan went first, picking whatever cut of steak was most expensive and asking about imported truffle butter with the casual entitlement of a man who’d never looked at a price column in his life.

“So, Dad,” he said once the waiter left, folding his hands like he was easing into a business meeting. “Now that the company’s officially sold, what happens to all the other stuff? The shipping routes. Those climate‑controlled containers you guys use for the… what do you call them… biologics?”

It caught me off guard.

“The logistics?” I said. “They’re part of the acquisition. The buyer takes over all the routes and infrastructure. Why?”

He shrugged, playing it off.

“Just seems like a waste to hand all that over, you know?” he said lightly. “Fast‑tracked lanes in and out of Europe, FDA clearances, all that. Somebody could build a whole separate business just on that system alone.”

I frowned. “Ryan, we’re not shipping sneakers. These are heavily regulated medical compounds. Federal agencies watch every box that moves. It’s not some side hustle.”

He laughed, hands up in surrender.

“Relax, I’m just curious,” he said. “I’m proud of you, remember?”

Emily nudged him under the table, her smile never faltering.

“Don’t grill him tonight,” she chided. “Just let Dad enjoy this.”

My phone buzzed then, vibrating against the linen. The caller ID flashed the name of the Swiss bank I’d just wired my life into.

“Sorry,” I said, standing. “I have to take this.”

“Of course,” Ryan said quickly. His hand brushed Emily’s under the table. “We’ll be right here.”

I slipped the little American flag toothpick out of my slider without thinking and rolled it between my fingers as I walked toward the lobby. It was a silly habit—something I did in tense meetings, a physical anchor. The paper flag crinkled softly.

“Mr. Shaw, this is Banca Suisse,” a crisp voice said when I answered. “Calling to confirm the incoming transfer of sixty million U.S. dollars. Funds are cleared and available. Congratulations.”

“Thank you,” I said.

It should have felt like the happiest sentence I’d heard in years.

Instead, my stomach tightened. Laura should’ve been there to roll her eyes at the number, to remind me to change the air filter in the hallway and pick up more dog food, sixty million or not. A wire transfer can’t hug you in the kitchen.

I slipped the phone back into my pocket and turned toward the dining room.

That’s when the young waiter materialized in front of me, blocking my path.

He couldn’t have been more than twenty‑four. Dark hair, clean‑shaven, white shirt starched so crisp it almost glowed under the lobby lights. His name tag read EVAN in neat black letters.

“Mr. Shaw?” he whispered.

“Yes?”

“I—uh—sir, I’m so sorry to bother you,” he said, eyes flicking toward the dining room and back. “But I… I think your daughter just put something in your glass.”

At sixty‑eight, I’ve lived through market crashes, lab accidents, and one very tense deposition. But I have never felt fear like the kind that flooded my body in that second.

My first instinct was denial.

“I think you’re mistaken,” I said slowly. “My daughter wouldn’t—”

“I was at the service station behind your table,” he rushed on, words tumbling over each other. “Your son‑in‑law got really loud about the painting on the far wall, asking her some big question about the artist, like he was onstage. You both looked over there. While you were turned, she—sir, she was fast. She took a little brown glass vial out of her purse, unscrewed it, and poured a white powder into your wine. Then she swirled it once and put it back in a napkin. Two, three seconds, tops.”

The lobby seemed to tilt.

“You’re sure?” I asked.

He swallowed hard.

“Yes, sir. One hundred percent. I saw it. I shouldn’t even be telling you this, I could get fired, but… I couldn’t just pretend I didn’t see it. It didn’t look right.”

In forty years of running a biotech company, I’ve seen what certain powders can do. Some heal. Some hurt. All it takes is the right dose.

The part of my brain that panics wanted to sprint back into that dining room and flip the table. The part that built a sixty‑million‑dollar company stayed very, very still.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Evan, sir.”

I reached for my wallet.

I don’t know why I did it. Maybe it was habit. Maybe it was gratitude. Maybe it was buying his silence and his safety at the same time.

I took out five crisp hundred‑dollar bills and folded them into his shaking hand.

“You didn’t see anything,” I said quietly. “You’re going to finish your shift, go home, and forget this ever happened. But if you ever need a job, or if you’re ever in trouble you can’t get out of, you call the number on this card.”

I slid my personal card into his other hand, the one that didn’t say CEO anymore.

“Sir, I—”

“Evan,” I said, my voice firm but not unkind. “Thank you. Now go.”

He slipped away like a shadow.

I stood in the lobby for a slow count of ten, feeling my heartbeat in my ears. The little paper flag in my hand had crumpled into a distorted shape, red and white stripes bent out of line.

Then I smoothed my suit jacket, rearranged my face into the polite distraction of a man on the phone with his banker, and walked back to my table.

That was the moment I stopped being a father out to celebrate and became a CEO in a crisis meeting.

When you suspect your child has just tried to stage your downfall, you learn very quickly what kind of man you really are.

Emily looked up the second I slid back into my seat.

“Everything okay, Dad?” she asked, smile wide, eyes bright. If I hadn’t known what she’d just done, I would’ve believed she was simply happy for me.

“Just the bank,” I said lightly, waving a hand. “Lawyers and loose ends. Nothing interesting.”

My wineglass sat exactly where I’d left it. Deep red. No visible powder. No strange scent.

“Did they confirm it?” Ryan asked, leaning forward, elbows on the table. “The transfer?”

“They did.”

Ryan let out a low whistle.

“Sixty million dollars,” he said. “My father‑in‑law, the sixty‑million‑dollar man. That has a nice ring to it.”

Emily giggled.

“Stop,” she said, swatting at him playfully. “You’re embarrassing him.”

They both watched me lift the glass.

I didn’t drink.

I set it down and reached for my water instead, letting my hand “accidentally” clip Ryan’s full glass and send it crashing over.

“Damn,” I said, jerking my arm back. Ice water splashed across the white tablecloth, soaked Ryan’s very expensive pants, and cascaded to the floor.

“Seriously, Peter?” Ryan snapped, pushing his chair back hard enough to screech against the marble. “These are suede.”

I put a hand to my forehead, letting embarrassment creep into my voice.

“I’m so sorry,” I said. “Clumsy old man over here. I guess the big day’s catching up to me.”

The waiter appeared instantly with a flurry of napkins. Emily turned in her chair to help Ryan dab at the spill, her back half‑turned to the table. For a few seconds, everyone’s focus was on the disaster I’d created.

My hands moved on their own.

Right hand: my original wineglass. Left hand: Emily’s.

I lifted both out of the splash zone, sliding them around the cluster of plates as the waiter worked. When I set them back down, they had traded places.

My tainted glass now stood directly in front of my daughter.

“Really, Dad, you scared me for a second,” Emily said, laughing as the waiter scurried off with a soaked tablecloth. “I thought maybe you were having a moment.”

“Just an accident,” I said, forcing a sheepish smile. “Guess I’m not meant for the high‑roller life.”

The funny thing about playing the fool is how quickly people believe you, especially when they’ve already decided you’re in the way.

“See?” Ryan said, smoothing his ruined pants with a sigh. “This is why we’re worried.”

“Worried?” I repeated.

“About you,” he said, tipping his glass in my direction before taking a sip. “About all this money you suddenly have to manage. It’s a lot, Peter. It would be easy for someone to take advantage of you.”

Emily picked up her wine—the glass that had once been mine.

“We just want to help,” she said, eyes soft. “We’ll make sure no one uses you.”

“To family,” I said quietly, lifting my clean glass.

“To family,” she echoed, and took a long, confident drink.

That was the moment the trap they had set for me quietly closed around her instead.

The next fifteen minutes might as well have stretched into fifteen years.

I pushed my steak around my plate, cutting small pieces, chewing slowly, tasting none of it. Ryan launched into a monologue about an expansion of his “import‑export” business, a phrase that sounded legitimate until you realized he never named a single product.

Emily laughed in all the right places, nodded at all the right times. But every couple of minutes, her smile flickered.

At first, it was subtle. She blinked harder than usual, like she couldn’t quite get her eyes to focus.

“Is it just me,” she said eventually, interrupting Ryan mid‑sentence, “or did they turn the lights up in here?”

Ryan chuckled.

“It’s L’Orangerie, babe,” he said. “Everything’s bright. That’s the point.”

She pressed her fingers to her temple.

“No, seriously, it’s… it’s like the room just shifted,” she said, voice a little too loud. “Dad, do you feel weird?”

“I feel fine,” I said.

That wasn’t entirely true. My heart was pounding, my mouth was dry, and my fork felt three times heavier than it should have. But my mind was sharp. I’d spent decades watching clinical trials. I knew what early neurological side effects looked like.

Emily tried to stand.

Her chair scraped loudly against the floor.

“I need some air,” she said, except it came out slurred. “Ryan, I… I don’t feel right. The room is spinning.”

She took one step. Her knees buckled.

Her eyes rolled back just enough to show too much white. She collapsed sideways into the plush velvet banquette, her body jerking in a small, awful seizure.

For a heartbeat, nobody moved.

Then every sound hit at once.

A woman at the next table gasped. Silverware clattered. Somewhere behind me, a waiter dropped a tray.

Ryan stared, frozen.

He didn’t reach for her hand.

He didn’t call her name.

He looked at me.

That was all I needed to see.

I shoved my chair back so hard the legs squealed.

“Emily!” I shouted, my voice cracking on purpose. “Oh God. Somebody call 911!”

I grabbed her limp hand, felt the faint pulse in her wrist. Her breathing was shallow, ragged.

“Help!” I yelled again. “My daughter, something’s wrong with my daughter!”

It took Ryan a full three seconds to snap out of it. When he did, he moved quickly—but not toward her.

“She’s fine,” he hissed, rounding on the restaurant manager who’d appeared at his shoulder. “She just mixed her anxiety meds with wine again. Happens all the time, she’s dramatic. We’ll get her home. No need to make a scene.”

He half‑bent, trying to haul her upright by the arm.

Her head lolled.

“Ryan,” I barked, letting fatherly panic bleed into fury. “She’s not okay. Look at her. She needs an ambulance.”

He shot me a look that could’ve peeled paint.

“If you call 911, they’ll run tests,” he said through clenched teeth, low enough that only I and the manager could hear. “They’ll make it a whole thing. She doesn’t need that. We don’t need that.”

What he meant was: if an ER doctor ran a tox screen, someone would have to explain why the daughter of a biotech founder had enough antipsychotic medication in her system to tranquilize a horse.

“Sir, it’s our policy—” the manager began.

“Your policy,” Ryan snapped, “is about to cost you a very big tip.”

“Already called,” a voice said behind him.

Evan stood at the edge of the chaos, his face pale but his jaw set. His phone was still in his hand.

“The dispatcher said not to move her,” he said loudly enough for the nearby tables to hear. “They’re less than five minutes out.”

Ryan spun on him like a rattlesnake.

“You did what?” he spat. “You just cost yourself your job, you little—”

“Mr. Ford,” the manager cut in sharply, stepping between them. “Our staff followed protocol. You need to step back.”

Sirens wailed faintly in the distance.

Ryan’s mask slipped for the first time that night.

For a split second, there was no charming entrepreneur, no concerned husband. Just raw, animal panic.

He looked at the spilled water, at the wineglass still upright in front of Emily’s slack hand, at me.

And I saw it hit him.

He didn’t know how I had done it. He just knew I had.

By the time the paramedics arrived, the trap he’d set for me had exploded in his face, and he was scrambling to shove the pieces back together.

The ER at St. Jude County Hospital smelled like antiseptic, burnt coffee, and fluorescent lights.

If you’ve never smelled fluorescent lights, trust me: there’s a hum to them that gets into your teeth. The automatic doors hissed open and swallowed Emily on a gurney, a swarm of blue scrubs around her. I followed, hunched, playing the part of the dazed older father who’d just watched his world collapse.

“Sir, you’ll need to wait here,” a nurse said gently, guiding me toward plastic chairs bolted to the floor.

Ryan tried to push past.

“I’m her husband,” he protested. “She’s allergic to shellfish. It must’ve been the scallops. Just give her epinephrine and let us go.”

The nurse didn’t even look up from the chart.

“Her airway is clear,” she said. “We’re not seeing signs of an allergic reaction. The doctor will be out to talk to you.”

We ended up in Trauma Bay 3, a curtained cubicle that somehow managed to feel both too open and too small. Emily lay on the bed, pale, an oxygen cannula under her nose, wires snaking from her chest to beeping monitors.

A young doctor in wrinkled scrubs stepped in, stethoscope hanging around his neck.

“I’m Dr. Chen,” he said, voice calm, eyes sharp. “Tell me exactly what happened.”

Ryan jumped in first.

“She must’ve had some bad shellfish,” he said. “She’s very sensitive. She does this sometimes when she mixes her anxiety meds with wine.”

Dr. Chen’s brows lifted.

“‘Does this’?” he repeated. “By ‘this,’ you mean collapses, seizes, and loses consciousness?”

Ryan faltered.

“Well, no,” he said quickly. “I just mean she gets dramatic. Look, I’m telling you, it’s just an allergy. We don’t need all these tests. Just give her something and let me take her home.”

Dr. Chen ignored him.

He lifted one of Emily’s eyelids, shining a small light into her pupil. It barely constricted.

He pinched the skin on the back of her hand. No response.

“This isn’t an allergy,” he said, more to himself than to us. “Her airways are clear. No swelling, no hives, no rash. Her pupils are pinpoint. Her reflexes are depressed.”

He looked up.

“Has she taken any medication tonight? Anything new?”

Ryan hesitated, then shook his head.

“No,” he said firmly. “She’s fine. You’re wasting time. I don’t consent to tests.”

That got the doctor’s full attention.

“I wasn’t asking for your consent to practice basic medicine on an unconscious adult in distress,” Dr. Chen said evenly. “If you continue to interfere, I’ll have security escort you out of this room.”

Ryan opened his mouth, then shut it. For the first time since I’d known him, he didn’t have a smooth answer ready.

I stepped in, letting my shoulders shake just enough.

“Doctor,” I said, my voice rough. “Please. Just help her. Do whatever you need to do. My son‑in‑law is in shock. He doesn’t know what he’s saying.”

Dr. Chen’s expression softened when he looked at me.

“Thank you, Mr. Shaw,” he said. “We’re going to run a full toxicology screen, a CT scan, and get her stabilized. You can wait in the family room. We’ll update you as soon as we know more.”

He turned to the nurse.

“Full labs, tox panel, head CT, Narcan just in case, and start a saline drip,” he ordered.

As they worked, Ryan grabbed my arm and pulled me aside.

“You’re making this worse,” he hissed. “He’s going to call the police. Do you have any idea what that’ll look like in the papers?”

“In the papers?” I repeated softly. “Your wife is unconscious, and you’re worried about headlines.”

He dropped my arm.

“Stay out of this,” he said. “I’ve got it handled.”

That was the moment I realized he wasn’t just playing with my daughter’s life.

He was playing with mine.

They sent us to a windowless waiting room with gray plastic chairs anchored to gray linoleum floors under buzzing gray lights. The coffee that bubbled in a stained machine in the corner tasted like someone had brewed it through old pennies.

Ryan paced.

I sat.

That’s the thing about being old: people assume you’re tired when you’re really just conserving energy.

He called someone—I could see the name REED flashing on his phone screen—turned his back, and hissed into the receiver.

“We have a problem,” he said. “She drank it. No, I don’t know how. The old man must’ve done something. I don’t care. The hearing is at eight a.m. We still have to make the conservatorship happen.”

He was too agitated to notice I’d slipped out of my chair and moved toward the vending machine just far enough to hear.

“You owe me, Reed,” he snapped. “Three hundred and ten grand in gambling markers. You’re not backing out now. You prescribed the stuff. You told us the dose. You’re going to get down here, you’re going to tell these ER clowns she’s unstable, and you’re going to testify that her dad is losing it. That was the deal.”

He paused, listening.

“Then you better start figuring it out,” he said. “Because if I go down, you go down. We’re both in this. The Shaw contingency is happening. Understood?”

The Shaw contingency.

That phrase hit me like a bucket of ice water.

I’d seen it before.

A week earlier, I’d been at Emily and Ryan’s house for dinner. Emily had asked me to help her find one of Laura’s old recipes on her laptop—something she’d supposedly scanned from Laura’s handwritten cards. When she went to answer the door for a delivery, I’d accidentally clicked into her email instead of her documents.

I wasn’t snooping; I was trying to get out. But one subject line had caught my eye.

“The Shaw Contingency – Draft,” it had read.

I’d assumed it was a surprise party. Some retirement joke. I’d closed the laptop and forgotten it.

Now, in that sterile waiting room, with my daughter unconscious two hallways away and my son‑in‑law plotting my legal funeral, I realized just how badly I’d underestimated the people who shared my last name.

Dr. Chen came back about an hour later.

He looked tired, but more than that, he looked angry.

“Mr. Shaw?” he asked.

I stood.

“Is she…?” I started.

“She’s stable for now,” he said. “We pumped her stomach, got the labs back, and administered an antidote for the medication she took. She’ll be very sick for a while and will require observation on a secure floor for at least seventy‑two hours.”

He turned to Ryan.

“Mr. Ford, I’d like to know why your wife has a near‑toxic amount of olanzapine in her system.”

Ryan blinked.

“I—I’ve never heard of it,” he said.

“It’s a powerful antipsychotic,” Dr. Chen said, his tone flat. “We use it to treat severe bipolar disorder and certain psychotic conditions. It is not, despite what you told me earlier, an anxiety medication. And it is absolutely not something anyone should be mixing with alcohol at that dose.”

He looked between us.

“When an otherwise healthy adult woman shows up in my ER with levels this high, protocol requires me to report it,” he continued. “Because from where I’m standing, it looks a lot like someone put her in extreme danger on purpose.”

He didn’t say the word. He didn’t have to.

Ryan sputtered.

“She—she must’ve mixed things up,” he said. “She’s been under a lot of stress. Her dad is selling his company. There’s money moving. It’s a lot. Maybe she just… made a mistake.”

Dr. Chen stared at him for a long beat.

“A mistake,” he repeated.

He turned back to me.

“Mr. Shaw, I’m very sorry you’re going through this,” he said more gently. “Your daughter will be moved to a monitored floor for her own safety. The police will want to ask some questions later. For now, there’s nothing more you can do here tonight.”

He hesitated.

“Do you have someone you can call?”

I thought of my empty yellow kitchen, the patriotic mugs lined up on the counter like soldiers without a general. I thought of Laura’s voice warning me. I thought of the man sitting next to me in that gray plastic chair—a man who had just tried to use medicine as a weapon.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

That was the moment I stopped trying to understand Ryan and started planning how to bury him.

By three a.m., I’d done two things I never thought I’d do in my life.

First, I’d slipped into my unconscious daughter’s hospital room, taken her purse from the chair, and fished out the small brown glass vial still wrapped in a linen napkin. A few grains of white powder clung to the inside.

Second, I’d used the spare key under the dead fern on their back porch to let myself into Emily and Ryan’s house while they thought I was in a cab heading home.

I told myself I was looking for understanding.

What I was really looking for was proof.

Their house was everything my little ranch wasn’t: high ceilings, floating staircases, a kitchen bigger than my first lab. The kind of place you bought not because you needed to live there, but because you needed other people to see that you did.

I knew exactly where Emily kept her laptop. On a white desk in a home office that smelled like designer candles and printer ink.

It was open.

No password.

Arrogance masquerading as convenience.

I sat down, clicked her email, and typed one word into the search bar.

“Reed.”

The results populated instantly.

Dozens of emails. Threads between Emily, Ryan, and a man named Dr. A. Reed.

I clicked the one with the subject line that had haunted me in the waiting room.

“The Shaw Contingency – Final Plan.”

Reading other people’s email is a violation. Reading your child’s is a kind of heartbreak that doesn’t have a proper name.

From: Ryan Ford

To: Dr. A. Reed

Cc: Emily Shaw Ford

Subject: The Shaw Contingency – Final Plan

Reed,

He’s becoming suspicious. Asking too many questions about the shipping manifests and the audit timeline. Once the deal closes, we’re finished if anyone looks too closely at those routes.

We have to move up the timeline.

Send the meds under a different name. We’ll handle dosage on our side. All you have to do is back us up when the time comes.

R.

From: Dr. A. Reed

To: Ryan Ford

Cc: Emily Shaw Ford

Subject: Re: The Shaw Contingency – Final Plan

The risk here is significant, but given my current situation with the markers, I don’t have many choices.

As discussed, the compound I’m prescribing will, at the dose recommended, induce acute confusion, slurred speech, and behavior that mimics a sudden neurological event in an older adult. The effects will appear similar to early dementia or a mini‑stroke.

He’ll look disoriented enough to justify an emergency psychiatric hold.

Once he’s at the hospital, I can certify that he’s no longer capable of managing his own affairs. The court will grant the conservatorship if we present as “concerned family members.”

Remember: it has to look like an accident or a stress reaction. No talk of “poison.”

A. Reed.

From: Emily Shaw Ford

To: Ryan Ford, Dr. A. Reed

Subject: Re: The Shaw Contingency – Final Plan

I’ll do it at the celebration dinner tomorrow night.

He trusts me. He always has. I’ll pour it into his wine when Ryan distracts him. Once the ER calls you, you come in as his “primary.”

We get the papers signed first thing in the morning.

Then we move the money before the feds start digging around in those shipments.

E.

There were more.

Dozens more.

An attached PDF from Jacobs & Hall, Attorneys at Law, Subject: “Emergency Petition – In re: Peter Shaw.”

I opened it.

My life reduced to legal bullet points.

Petitioner: Ryan Ford, son‑in‑law.

Respondent: Peter Shaw, age 68.

Grounds: Rapid cognitive decline, confusion, financial irresponsibility, vulnerability to undue influence, potential danger to self and others.

Suggested Guardian: Ryan Ford.

Supportive Witness: Dr. Albert Reed, primary physician.

Hearing Time: 8:00 a.m., November 4, Department 3B, County Courthouse.

I stared at the time until the numbers blurred.

It was 3:05 a.m.

Five hours from the moment my daughter had tried to put something in my drink, her husband and their doctor were planning to stand in front of a judge and persuade him that I was a danger to my own bank account.

They weren’t just trying to steal my money.

They were trying to erase me.

The little crumpled paper flag was still in my pocket, forgotten until I felt the corner dig into my palm as I closed Emily’s laptop.

I took it out and flattened it on the desk.

Stars, stripes, cheap ink.

Four decades of doing things the hard way in this country, and my exit plan was going to be a forged medical opinion and a rushed family court hearing.

“Not today,” I said to the empty room.

My voice sounded steady.

“Not ever.”

That was the moment I stopped being their plan and started making mine.

At 4:30 a.m., I walked into the downtown high‑rise where my attorney kept his office and buzzed the elevator for the top floor.

Most lawyers would’ve told me to wait until business hours.

Harrison Wright was not most lawyers.

His lights were already on.

He stood by the floor‑to‑ceiling windows of his corner office, tie loosened, shirtsleeves rolled, a pot of coffee steaming behind him on a credenza. The city below looked small and far away, like something on a model train set.

“This had better be a matter of national security, Peter,” he said without turning around.

“It’s worse,” I said, closing the door behind me. “It’s family.”

He turned then.

One look at my face and his expression shifted from mild annoyance to something like interest.

“Sit,” he said. “Start from the top.”

I sat in the same leather armchair I’d used to negotiate the Apex sale. My hand brushed against something on the armrest.

The little paper flag.

I hadn’t even realized I was still holding it. Without thinking, I set it down next to his expensive fountain pen.

Then I told him everything.

I told him about the wire transfer. The dinner. The waiter. The vial. The switched glasses. The collapse. The ER. Dr. Chen. The toxicology report. The word olanzapine. The mandatory report. The overheard phone call. The Shaw contingency emails. The PDF.

I didn’t embellish. I didn’t dramatize. Years of board meetings had taught me how to deliver bad news cleanly.

By the time I got to the part about the 8:00 a.m. hearing, Wright’s jaw was clenched so tight a muscle in his cheek jumped.

“They were going to walk into a courtroom in four hours and get you declared incompetent,” he said quietly. “With a doctor on payroll and your own daughter as the tearful witness.”

I nodded.

“And after that?” he asked.

“They move the sixty million into accounts I can’t touch,” I said. “They bury whatever Ryan’s been doing with my shipping lanes before the federal audit starts. They put me somewhere with soft walls and call every now and then to make themselves feel better.”

Wright poured coffee into two mugs, set one in front of me, and leaned against his desk.

“Do you remember that patent troll case we won three years ago?” he asked.

I frowned.

“The one where you made their expert witness cry on the stand?”

He nodded once.

“I don’t like bullies,” he said. “And I really don’t like people who use the courts as a blunt instrument.”

He picked up the paper flag, turned it between his fingers.

“Let’s see how they like it when the instrument swings back.”

That was the moment the battle lines shifted from my kitchen table to a courtroom.

By 6:00 a.m., Wright had done three things.

First, he’d forwarded the entire “Shaw Contingency” email chain and the emergency petition PDF to a secure server, cc’ing a private investigator named Peterson with the subject line: “Everything you need to ruin a doctor’s day.”

Second, he’d called a contact at the local FBI field office—Special Agent Davies—and left a message that could politely be summarized as “you’re going to want to sit in on this hearing.”

Third, he’d made me practice.

“Again,” he said, pacing the length of his office as the sky slowly lightened outside.

I slumped in the chair, let my shoulders sag, and let my voice tremble.

“I don’t understand, son,” I said, staring down at my hands. “What hearing? Why is everyone talking about lawyers? I just want to go home.”

He shook his head.

“Too coherent. You’re a scared dad, not a confused one. He needs to think he’s still ahead of you.”

We both jumped when my phone rang.

Ryan.

Wright nodded at the device.

“Speaker,” he mouthed.

I answered.

“Hello?” I said, letting a little static into my tone. “Who is this?”

“Dad, thank God,” Ryan said. His voice oozed relief. “Where are you? I’ve been calling your cell, your house. I was about to file a missing persons report.”

“I… I couldn’t be there,” I said, looking down at the flag on Wright’s desk. “The house. Your mother’s things. I’m at some diner, I think. I just started driving. I needed to think.”

He jumped on it.

“A diner? Dad, listen to yourself,” he said. “Dr. Reed is very concerned about you. He says what happened to Emily could be a hereditary neurological thing. He’s on his way to your house right now. I’m meeting him there. We need to make sure you’re okay.”

I let silence stretch.

“A doctor?” I said finally. “At my house? No. No, I don’t want a doctor at my house.”

“Dad,” he said, soft and firm at the same time. “You don’t have a choice. You’re not thinking clearly. You scared us last night, running off like that. You’re upset. You’re confused. This is for your own good.”

There it was. The story he planned to tell the judge later, rehearsed on me first.

“You just go home,” he continued. “Have some coffee, calm down. Let Dr. Reed check you out. We’ll take care of everything. Okay?”

I let my breath hitch.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll go home.”

“Good,” he said. “We’ll be there in thirty minutes.”

I hung up and looked at Wright.

“He’s sending his star witness to an empty house,” Wright said, already gathering his files. “Perfect. Let him knock on the door for an hour while we’re at the courthouse introducing his plan to a judge and, if I’m lucky, to federal agents.”

He slipped the tiny paper flag into his breast pocket.

“Let’s go remind your son‑in‑law who built the life he’s trying to hijack.”

That was the moment I stopped fearing the hearing and started looking forward to it.

The hallway outside Department 3B of the county courthouse smelled like old paper and cold air.

Wright and I waited at the far end, just out of sight of the wired glass window in the door. Through it, I could see Ryan pacing at counsel table in his best suit, which I recognized from the last wedding we’d all been at together.

He looked terrible.

His tie was slightly crooked. His eyes were bloodshot. His hair, usually styled within an inch of its life, had a rogue wave. Beside him sat a young attorney in a shiny suit whose body language screamed, “I passed the bar and bought this briefcase on the same day.”

On the front bench, hands clasped so tight his knuckles were white, sat Dr. Reed.

He looked like a man who’d just realized the horse he’d bet his last chips on had broken a leg on the way to the gate.

“They think you’re not coming,” Wright murmured.

Inside, the bailiff called the room to order.

“All rise,” he said. “The Honorable Judge Anderson presiding.”

We stayed where we were.

The judge—a man in his sixties with a reputation for having zero patience for nonsense—took the bench.

“We are here on an emergency petition in the matter of Peter Shaw,” he said, voice dry. “Petitioner?”

Ryan’s lawyer stood.

“Michael Jennings for the petitioner, Your Honor,” he said. “Mr. Ryan Ford, Mr. Shaw’s son‑in‑law.”

“And where is Mr. Shaw?” the judge asked, glancing at the empty side of the room.

Jennings put on a rehearsed sad face.

“That’s part of why we’re here, Your Honor,” he said. “Mr. Shaw is missing.”

He let the word hang.

“Last night, he suffered a severe episode at a restaurant,” Jennings continued. “He became agitated, caused a dangerous scene, and then fled. This morning, my client and Dr. Reed, his primary care physician, went to his home for a wellness check.”

He spread his hands.

“They found the house empty. No note. No sign of where he’d gone. His car is missing. With his cognitive issues and the recent sale of his company for sixty million dollars, we’re terrified he’s out there alone with access to enormous resources and no judgment.”

He sighed, the weight of “concerned” family resting on his shoulders.

“We’re here to request an emergency guardianship so my client can secure Mr. Shaw’s assets and get him the care he so clearly needs,” he finished.

The judge nodded slowly.

“Very well,” he said. “Call your first witness.”

Jennings smiled.

“We call Dr. Albert Reed.”

As the bailiff administered the oath, Wright touched my elbow.

“Now,” he whispered.

He pushed the door open just as Dr. Reed’s hand fell from the Bible.

“I apologize for the interruption, Your Honor,” Wright said, his voice filling the room like a sudden storm. “Harrison Wright, counsel for Mr. Peter Shaw, who is very much not missing.”

Every head turned.

I walked in behind him.

I wore the same navy Zegna suit I’d worn to the Apex closing and polished shoes that squeaked softly on the linoleum. My hair was combed. My gaze was steady.

Ryan spun around.

For a split second, his face went completely blank, like a computer screen gone dark.

Then the color drained away.

“Dad,” he blurted.

I looked at him. I didn’t say a word.

Judge Anderson peered over his glasses.

“Mr. Jennings,” he said slowly. “You told this court your client’s father‑in‑law was missing.”

Jennings swallowed.

“Your Honor, I—I can only say this is as much a surprise to us as it is to you,” he stammered. “Mr. Shaw’s erratic behavior only underscores—”

“It underscores that your facts are sloppy,” the judge cut in. “Sit down, Mr. Jennings. Dr. Reed, you may proceed with your testimony. I’m suddenly very interested in hearing your view of Mr. Shaw’s condition.”

Reed looked like he might be sick.

“Doctor?” Jennings prompted.

Reed cleared his throat.

“Y‑yes,” he said. “As I was saying, Your Honor, I’ve been consulting on Mr. Shaw’s case for several months at his son‑in‑law’s request. In my professional opinion, Mr. Shaw is experiencing a rapid cognitive decline. He’s forgetful, paranoid, easily agitated. Last night’s behavior—fleeing a stressful situation, disappearing—it all aligns with that.”

“And is he capable of managing complex financial matters?” Jennings asked.

“In my opinion, no,” Reed replied. “He’s vulnerable. He could be taken advantage of. An emergency guardianship would protect him.”

Jennings nodded.

“No further questions.”

“Mr. Wright?” the judge asked.

Wright rose.

“Just a few,” he said mildly.

He approached the stand with a file in hand.

“Dr. Reed, you said you’ve been consulting on Mr. Shaw’s case for several months,” he began. “Is that right?”

“Yes.”

“Interesting,” Wright said. He opened the file. “Because these are Mr. Shaw’s medical records from the last twenty years. His primary care physician of record is Dr. Harris Patel. There is no mention of you anywhere.”

Reed shifted in his seat.

“I—these were house calls,” he said. “Informal. At the family’s request.”

“I see,” Wright said. “And when was the last time you saw Mr. Shaw?”

“This morning,” Reed said quickly. “At his home. He was confused and agitated. He ran out while we were there.”

“I see,” Wright repeated. “At what time?”

“Around seven,” Reed said.

Wright smiled a small, cold smile.

“That’s remarkable,” he said. “Because at seven this morning, Dr. Reed, Mr. Shaw was sitting in my office, drinking coffee, and preparing for this hearing. I have security footage and two paralegals who will happily testify to that.”

He let that sink in.

“So either you have a very loose relationship with time,” Wright continued, “or you’re lying under oath.”

Jennings shot to his feet.

“Objection, Your Honor,” he said. “Counsel is badgering the witness.”

“Overruled,” the judge said. “I’d like to hear where this is going.”

“Let me help you, Doctor,” Wright said, turning a page in his file. “Medicine is stressful. Money can be, too. You’re familiar with RF Imports?”

Reed blinked.

“I don’t—”

“It’s a shell company,” Wright said conversationally. “Owned by your patient’s son‑in‑law, Ryan Ford. It also happens to be the entity that’s been wiring ten‑thousand‑dollar payments every two weeks into your offshore account in the Caymans for the last six months.”

He flipped the easel to reveal a blown‑up bank statement.

“Total as of last week: three hundred and ten thousand dollars,” he said. “Which, by a fascinating coincidence, is almost exactly the amount you currently owe to an online sports betting operation. Would you like me to read out the names of your favorite teams?”

Reed’s mouth opened and closed like a fish.

“I—this is—my finances are private,” he managed.

“Not when you’re being paid off by the petitioner in a guardianship hearing,” Wright said. “So let’s try this again. How much is your integrity worth, Doctor? Apparently about three hundred and ten grand.”

Color flooded Reed’s face, then drained just as fast.

“He said he’d ruin me,” Reed blurted, voice cracking. “Report me to the board. Take my license. He said it was just paperwork. That the old man was already slipping.”

“‘He’ being Mr. Ryan Ford?” Wright asked.

“Yes,” Reed whispered.

“And the medication?” Wright asked. “Who requested the olanzapine?”

“Ryan,” Reed said. “He told me what dose to prescribe. He said they needed something that would make Mr. Shaw look confused, not sick, so the judge would believe he couldn’t handle the money. He called it the Shaw contingency.”

Silence settled over the courtroom like a blanket.

Jennings sank slowly into his chair.

Ryan stood.

“He’s lying,” Ryan shouted, pointing at Reed. “They’re in this together. My father‑in‑law is the one who put something in Emily’s glass. He’s out of his mind. You all saw him. He’s staging this. He—”

“Mr. Ford, sit down,” the judge said sharply.

Ryan didn’t.

Instead, he lunged.

He vaulted over the petitioner’s table, hands reaching for my throat.

He never made it.

Two men at the back of the courtroom who had been sitting very still in very boring suits moved in a blur. They intercepted Ryan mid‑air, taking him to the ground with a thud that shook the benches.

One of them stood, producing a badge.

“Special Agent Davies, FBI,” he said calmly. “Mr. Ford, you’re under arrest for conspiracy to commit fraud, for interfering with federally regulated shipping, and for bribing a medical professional to falsify records. You have the right to remain silent.”

Ryan thrashed.

“I’ll fix this!” he screamed. “Dad, tell them! Tell them you’re confused! You need me!”

I looked at him—the man my wife had warned me about, the man my daughter had chosen, the man who had tried to turn medicine into a weapon and the courts into a playground.

“I don’t need you, Ryan,” I said quietly. “But you’re going to need a very good lawyer.”

That was the moment the trap he’d built around me closed around him instead.

In the end, the legal part went faster than the emotional part.

The judge dismissed the emergency petition on the spot. He referred Dr. Reed to the medical board with a recommendation that made the doctor turn even paler. He sealed portions of the record pending federal investigation.

By the time I walked out of the courthouse into the pale November sunlight, reporters were already gathering on the steps, microphones in hand, questions ready.

“Mr. Shaw! Is it true your son‑in‑law tried to get control of your sixty million?”

“Is your daughter involved?”

“Did you know your company’s shipping lanes were being used for illicit imports?”

I didn’t answer.

I wasn’t thinking about headlines. I was thinking about a yellow kitchen, a dead fern, a glass of wine, and a daughter lying in a hospital bed on a locked floor.

“Car’s this way,” Wright said, steering me toward the curb.

“I need to see Emily,” I said.

He studied my face for a second.

“Are you sure?”

No.

“Yes,” I said.

He nodded.

“I’ll have my office coordinate with the FBI and Dr. Chen,” he said. “Go talk to your daughter. We’ll handle the rest.”

On the way down the steps, something fluttered to the sidewalk.

Wright bent and picked it up.

The little paper flag.

He handed it to me.

“You dropped this,” he said.

I looked at it for a long moment before slipping it back into my pocket.

The symbol of a celebration turned into a reminder: nothing about this country is guaranteed except the fight you’re willing to put up for what’s yours.

That was the moment I realized winning the legal war was the easy part.

The hard part was walking into my daughter’s hospital room.

The psychiatric observation floor at St. Jude was quieter than the ER. Quieter, but heavier.

A police officer sat on a plastic chair outside Emily’s door, scrolling his phone.

“Mr. Shaw?” he asked when I approached.

“Yes.”

“You can go in,” he said, standing. “She’s awake. Doctor said ten minutes.”

I nodded and pushed the door open.

Emily sat propped up against white pillows, IV line taped to her arm, hospital bracelet encircling her wrist. Her hair was tangled, her face washed clean of makeup. On the wall, a small TV played muted news footage.

She was watching Ryan being led out of the courthouse in handcuffs.

When she saw me, she flinched like I was a stranger.

“Dad,” she whispered.

Her voice was hoarse, like she’d been crying or screaming or both.

“What… what happened?” she asked. “I woke up and they told me I’d been here all night, and then I turned on the TV and—”

She gestured weakly toward the screen, where a banner screamed BIOTECH FOUNDER’S SON‑IN‑LAW ARRESTED IN FEDERAL PROBE.

“What did you do to him?” she demanded.

Not: “What did he do?”

Not: “What did I do?”

“What did you do, Dad?”

I closed the door behind me and walked to the window.

From up here, the city looked small again. Ambulances like toys in the parking lot, people like ants on the sidewalk.

“I told the truth,” I said.

“He said you’re losing it,” she said. “He said you ran around the restaurant yelling. That you tried to hurt him at the hospital. That you’re paranoid and you’re trying to frame him because you don’t want to let go of the company.”

I turned.

“And what do you think?” I asked.

She looked away.

“I think…” she started, then stopped. “I think I made a mistake last night.”

“A mistake,” I repeated.

“I wasn’t trying to hurt you,” she said quickly. “Ryan said it was just something to calm you down, to make you less stubborn for the paperwork. He said you’d be comfortable, that we’d be able to protect you. He said you were forgetting things. You did miss that dinner the other week.”

“You cancelled it,” I said. “You texted to say you’d mixed up the date.”

She blinked.

“I…”

“You poured a drug into my glass,” I said, keeping my voice even. “Whatever you told yourself about your intentions, that’s what you did. If I hadn’t switched them, I’d be the one in this bed, babbling about lights being too bright while your husband marched my signature into a courtroom.”

Tears spilled over.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

I’d always imagined that when my daughter apologized to me for something truly terrible, I’d feel vindicated. Relieved. Something.

I felt… tired.

“You chose him,” I said softly. “Again and again. Over my judgment. Over your mother’s instincts. Over common sense. Over your own conscience.”

She shook her head, sobs shaking her shoulders.

“He said you were going to blow everything,” she said. “That you’d give the money away to labs and charities and leave us with nothing. He said we deserved security after everything we’d been through with Mom. He said we needed to act before someone else took advantage of you.”

“And did any part of you,” I asked, “think to just… ask me?”

She stared at me, mouth open.

I let the silence stretch.

The beeping of the monitor filled the room like a metronome.

“I’m going to make sure you don’t go to prison,” I said finally.

Her head snapped up.

“What?”

“I’m going to use part of that sixty million to pay very good lawyers to argue that you were under the influence of a manipulative spouse, that you were emotionally compromised, that you panicked and made a catastrophic choice in a moment of grief and fear,” I said. “They’ll talk about complicated family dynamics. They’ll talk about your mother’s illness. They’ll talk about anything they have to talk about to keep you out of a cell.”

Fresh tears spilled.

“Dad, I—”

“I am also,” I continued, “going to pay for you to get help. Real help. Not a spa. Not a ‘wellness retreat.’ A place where you have to sit in rooms with professionals and unpack how you went from being the little girl who cried when her goldfish died to a woman who could watch her father raise a glass she’d tampered with and still say, ‘To family.’”

She flinched.

“And after that?” she whispered.

“After that,” I said, “you’re going to work.”

She blinked.

“At what?”

“At whatever job will take you,” I said. “You’re going to find out what it feels like to live on an hourly wage in a city that doesn’t care who your father is. You’re going to learn what a dollar feels like when you have to earn it instead of watch someone else transfer it.”

Her eyes widened in horror.

“You can’t be serious,” she said. “Dad, I’ve never—how am I supposed to—what about the money?”

“What about it?”

“Am I not getting anything?” she asked, voice small.

“You’re getting exactly what you earned,” I said. “Right now, that’s a second chance at staying out of a jumpsuit and an opportunity to rebuild your character from the ground up. The sixty million is going into a trust with strict conditions that will be enforced by people who are not related to you.”

“That’s not fair,” she whispered.

“Fair,” I said, “would’ve been me sitting in a courtroom drooling on myself while your husband argued that I was a danger to my own bank account. Fair would’ve been me never knowing you were capable of what you did. This isn’t about fair. This is about making sure that if you ever have any kind of power again, you understand what it looks like when people misuse it.”

She fell back against the pillows, sobbing.

I stood.

The little paper flag was in my pocket, the edges worn soft from my fingers.

“You’ll be discharged to a facility in a few days,” I said. “After that, you’ll report to your new job. Your supervisor knows who you are. He also knows what you did. He’s under strict instructions not to treat you any differently than any other employee.”

“Who is he?” she asked, wiping her face with the back of her hand.

“His name is Evan,” I said. “You almost cost him his job the night you tried to cost me my mind. Now he’s going to teach you how to clean toilets in a homeless shelter.”

She stared at me, stunned.

“You put me in a shelter?” she choked.

“I funded it,” I said. “Eight million goes to labs studying the diseases Laura fought. Five goes to beds and hot meals for people your husband would’ve stepped over on the sidewalk without seeing. You’re going to scrub those floors until you understand the value of a second chance.”

I walked to the door.

“Dad,” she sobbed. “Please. Don’t leave me.”

I paused with my hand on the handle.

“I love the little girl you were,” I said. “I don’t know the woman you’ve become. If you want me back in your life someday, earn it.”

That was the moment I stopped trying to be her safety net and decided to become her mirror instead.

Six months later, my life looked smaller from the outside and infinitely bigger from the inside.

I still lived in the same three‑bedroom ranch house. The same yellow kitchen. The same creaky step in the hallway that had annoyed Laura for decades and that I still hadn’t fixed because it made the house sound like itself.

The sixty million sat in a trust, growing quietly under the watchful eye of a young man who used to refill water glasses for a living.

“Your quarterly report, Mr. Shaw,” Evan said, setting a leather folder on my kitchen table one crisp afternoon.

The sunlight caught the paper flag stuck to a magnet on my refrigerator door. I’d flattened it, taped it to a cheap souvenir magnet from a gas station off I‑80, and given it a permanent place in my line of patriotic clutter.

“Tell me the good news first,” I said, pouring coffee into two of Laura’s old mugs.

“Markets have been steady,” he said, flipping to a colored chart. “The trust has grown by about 7%. The foundation’s first grant cycle funded three labs, two community clinics, and the shelter.”

“How’s the shelter?” I asked.

He hesitated just a fraction.

“Crowded,” he said. “Which is bad and good. Bad because that means a lot of people need it. Good because at least they have somewhere to go. The bathrooms have never been cleaner, though.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“Oh?”

“Emily hasn’t missed a shift,” he said. “She complains quietly, but she works. Her supervisor says she’s… different from when she started.”

“Different how?”

“She listens more,” he said. “Talks less. She seems to actually see the people in front of her now, not just the mess.”

I nodded slowly.

“And Ryan?” I asked.

“In federal custody,” Evan said. “His attorney’s trying to cut a deal. Your cooperation with the shipping investigation has helped a lot of people downstream, by the way. There were some very bad actors using your good name.”

“Not anymore,” I said.

We went through the rest of the numbers. Investments. Grants. Legal updates. All the invisible machinery that sixty million dollars sets in motion when you decide it’s going to do more than sit in an account.

When we finished, Evan closed the folder.

“Can I ask you something, Mr. Shaw?” he said.

“Of course.”

“Most people I know who make that kind of money either disappear or build a bigger house,” he said. “You put it in a trust, kept your old car, and spend most afternoons in this kitchen. Aren’t you… tempted?”

“To do what?” I asked.

“Buy the fancy life,” he said. “The one your daughter thought she was entitled to.”

I looked at the paper flag on the fridge.

“I built a company that changed some lives,” I said. “Then I built a trap for a man who tried to use that company to harm people. Somewhere in there, I almost lost myself.”

I took a sip of coffee.

“Turns out the thing that makes me sleep at night isn’t the size of my house,” I continued. “It’s knowing exactly where every dollar goes, and knowing that the people who tried to take everything from me are earning their way back to whatever kind of life they have left.”

Evan nodded.

“That makes sense,” he said.

We sat in quiet for a moment.

“Do you ever talk to her?” he asked finally.

“Emily?”

“Yeah.”

“Not yet,” I said. “She sends letters from the shelter, sometimes through the caseworkers. I read every one. I haven’t answered. Not because I’m cruel. Because I want to see who she’s going to be when the story stops being about what her husband did and starts being about what she’s doing now.”

He watched me, thoughtful.

“What if she never changes?” he asked.

I looked at the little flag.

“Then I’ll know,” I said. “And I’ll be sad. And I’ll still sleep at night, because I gave her a chance to be better than the worst thing she ever did.”

He closed his folder and stood.

“Well,” he said, “your projections look good, your foundation is doing what it’s supposed to, and your daughter is on toilet duty for the foreseeable future. I’d call that a productive quarter.”

I chuckled.

“Not bad for a retired mailman,” I said.

He grinned.

“Not bad for the sixty‑million‑dollar man,” he corrected.

After he left, I stood alone in the yellow kitchen, coffee mug warm in my hands.

The TV in the living room murmured softly about markets and politics and weather. Somewhere three bus rides away, my daughter was mopping linoleum, listening to stories from people who had learned the hard way what happens when you trust the wrong person or make the wrong bet or run out of safety nets.

I looked at the flag on the fridge.

Once, it had been a decoration on an overpriced appetizer at a restaurant where my daughter tried to turn me into a problem to be handled.

Now, it was a reminder of the night I refused to become that problem.

This whole story, when you strip away the legal jargon and the zeros in the bank account, comes down to something brutally simple: who you become when someone tells you there’s a shortcut.

Ryan saw sixty million dollars and a network of clean shipping routes and thought, Why build when I can take?

Emily saw a husband with big promises and thought, Why question when I can believe?

Dr. Reed saw three hundred and ten thousand dollars in markers and thought, Why confess when I can lie?

I saw a little paper flag and a glass of wine and thought, Why roll over when I can stand up?

I chose to stand.

Would you?

If you’d been in my shoes that night at L’Orangerie, with Sinatra in the background and the city spread out beneath you and your daughter smiling over a glass you knew she’d tampered with—would you have switched the glasses?

Would you have let the trap snap shut around her instead of you?

Some people will say what I did was cold. That cutting my daughter off financially while paying to keep her out of a cell is revenge dressed up as mercy.

Maybe they’re right.

Or maybe it’s something harder and rarer: accountability.

In the end, money didn’t change who any of us were.

It just turned up the volume.

And if there’s one thing I’ve learned after six decades of walking mail routes, running labs, signing paychecks, burying a wife, and watching my only child almost throw her soul away for a shortcut, it’s this:

You can’t buy your way out of who you are.

You can only decide, one hard choice at a time, to be better.

The night my daughter tried to erase me, I decided not to disappear.

The day I walked into that courtroom with a little paper flag in my pocket, I decided what kind of man I was going to be in the face of betrayal.

And every time I pour coffee into one of Laura’s old mugs and look at that flag on the fridge, I remind myself of the promise I made in that yellow kitchen after the closing call:

I will live like a man who knows exactly what his life is worth—and who will never again let anyone else write that number for him.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load