A cheap American flag magnet held my son’s birthday invitation to the freezer door while I changed the locks on our front door.

The magnet was red, white, and blue, the kind you grab at a dollar store around the Fourth of July and then forget about. It pinned up a piece of cardstock Mason and I had designed together: bold superhero colors, a cartoon city skyline, big block letters announcing his tenth birthday. First double digits. RSVP: Grandma, Aunt Amanda, cousins, everyone.

Ten days after the party nobody came to, that invitation was still there, edges starting to curl. The only thing that had changed in our small Chicago rental was the hardware on the door.

“Do you really have to change them, Dad?” Mason asked from the hallway, his voice small but trying to be brave.

“Yeah, buddy,” I said, tightening the last deadbolt. “Sometimes, when people keep walking in and out of your life like they own the place, you have to remind them they don’t.”

He didn’t fully understand. He was ten, still in his Spider-Man T‑shirt, the same one he’d worn to the party where no one showed up. But he watched me like it mattered, like every turn of that screwdriver was another piece of proof that he wasn’t the problem.

Last month, I spent three weeks planning Mason’s tenth birthday party, his first double digits, a superhero bash he’d been dreaming about for months. I’m Camden, a thirty-four-year-old single dad, raising my son alone since my wife walked out four years ago. I don’t have a lot of extras, but I had a little bit of savings, some overtime pay, and this stubborn belief that if I gave my kid one perfect day, it might make up for all the imperfect ones.

We rented a party room at a family center on the northwest side of Chicago, nothing fancy. I strung up red and blue streamers, ordered a cake with his favorite hero flying across it, and set out paper plates with tiny flags in the corner. Mason helped tape balloons to the door, checking his reflection in the glass, his brown hair slicked back the way he thought looked grown-up.

I personally called every family member. I didn’t just send a group text; I dialed my mother, Patricia, my sister, Amanda, my cousins. I mailed handmade invitations Mason had helped decorate, his messy handwriting a dead giveaway on every envelope.

“Do you think Grandma will come?” he asked the night before, sitting at the kitchen table while I filled goodie bags.

“She said she would,” I answered, more confident than I felt. “She knows this is a big one, buddy. First double digits.”

The day arrived, bright and cold, the kind of Midwestern Saturday where the sky looks like it’s made of tin. We stood in that decorated room for three hours.

Nobody came.

Not a single relative walked through the door. Not my mother. Not Amanda. Not a cousin running late. The only people who crossed the threshold were the teenage staff member checking the time and a tired mom asking if we were using the bounce house.

Mason tried to keep it together. He bounced alone for a while, slid down the inflatable slide, ate one slice of his own cake. Every few minutes he’d glance at the door like maybe this would be the moment the people who shared his blood remembered he existed.

About two hours in, he tugged on my sleeve.

“Dad?”

“Yeah, Mase?”

“What’s wrong with me?” he asked.

If you’ve never had your ten-year-old look you in the eye and ask what’s wrong with them because a room full of empty chairs is shouting louder than any words, I hope you never do. That question gutted me more cleanly than any knife could.

“There is nothing wrong with you,” I said, kneeling so we were eye level. “There’s something wrong with them.”

He nodded, but his eyes didn’t quite believe me. Kids hear what you say, but they feel what you do, and what my family did was stay home.

We packed up the untouched goodie bags, half a sheet cake, and a bunch of helium balloons no one had claimed. I loaded them into my aging SUV while Mason held the door, party favors brushing his shoulder as they swayed.

I told myself maybe something had happened. Maybe there had been an emergency. Maybe my mom’s phone had died, Amanda’s car had broken down, all those maybes lined up like tiny life rafts I kept trying to climb onto.

A week later, my phone finally pinged with a text from my mother.

Not to apologize.

Not to ask how Mason was, or why I hadn’t called.

The message was a mass text to our entire extended family.

“Hi everyone! My niece’s Sweet 15 is coming up in Miami this June. We’ve booked a beautiful venue on the beach. Cost is $2,600 per person all-inclusive. Venmo me to reserve your spot. Don’t miss this once-in-a-lifetime celebration!”

I stared at the screen, standing in my tiny kitchen, the hum of the fridge loud in the silence. The same cheap American flag magnet held Mason’s birthday invitation in place, the party date now a week behind us, like a joke the universe was in on.

There was no, “Sorry we missed Mason’s party.”

No, “How did it go?”

Just a dollar amount—$2,600 per person, as if that were a normal, reasonable thing to ask from a son who’d watched his child cry over empty chairs. As if their absence at my kid’s party was a rounding error on the spreadsheet of our family.

My thumb hovered over the keyboard. Years of training kicked in—the urge to smooth things over, to make excuses for them, to send back something polite.

Instead, I opened my banking app, the one that showed the hit from the party room rental, the cake, the decorations bought with overtime pay from drafting late into the night. My account didn’t have $2,600 lying around per person. It barely had $260.

I went back to the text thread and did something I’d never done before.

I hit Venmo.

Amount: $1.00.

Note: “Congratulations.”

It was petty. It was tiny. It was the emotional equivalent of flicking a pebble at a brick wall. But as I pressed send, something that had been knotted in my chest for thirty-four years loosened just a little.

Then I blocked my mother’s number.

I blocked Amanda’s.

I changed the locks on my front door.

I made a quiet promise—to myself and to Mason—that we were done auditioning for a role in a family that had already decided we didn’t belong in the cast.

Two days later, a black-and-white Chicago police cruiser pulled up to the curb in front of my house.

Mason was on the couch, building a Lego city on the coffee table. Sinatra played softly from the old Bluetooth speaker I’d picked up at a yard sale, the same playlist I’d had on during the party as we waited for guests who never came. I saw the cruiser through the thin curtains, the blue-and-red lights off but the presence unmistakable.

Someone knocked on the door.

“Daddy?” Mason’s voice wobbled. “Did I do something?”

“No,” I said, forcing my voice steady. “You didn’t do anything.”

I wiped my hands on my jeans, glanced once more at the freezer door where the American flag magnet held that fading invitation, and opened the door to two uniformed officers.

“Mr. Camden Hayes?” the taller one asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“We got a call from your mother. She’s concerned about your son’s wellbeing. Mind if we talk for a minute?”

Of course she had called the police.

Not when her grandson’s party room sat empty.

Not when her son worked two jobs in high school or juggled bills as an adult.

She called when I finally set a boundary.

If you’re reading this on your phone somewhere in the States, maybe on a lunch break or late at night in a quiet apartment like mine, you might already know this flavor of disappointment. The kind that’s less like a lightning strike and more like a slow leak in the ceiling you’ve learned to live under. I’m telling this story because there are a lot of us out here trying to rebuild after betrayal, trying to raise kids who don’t inherit our scars.

But to understand how I got to the point where a $1 Venmo and a changed lock brought the police to my porch, you have to go back to where all of this started.

You have to go back to Elmwood Park.

I grew up in a modest two-story house in Elmwood Park, a suburb just outside Chicago where the backyards were small, the Fourth of July parades were big, and everyone knew everyone else’s business. Inside our beige-sided house, my family’s business was that my sister Amanda was the sun, and the rest of us orbited around her.

My mother, Patricia, made it clear early on that Amanda was the golden child destined for greatness, while I was just… there. Present, useful when needed, forgettable when not.

The same kind of American flag magnet that now holds my son’s invitation used to live on my parents’ fridge too. Back then, it pinned up Amanda’s perfect report cards, her honor roll certificates, glossy photos from her dance recitals. When I brought home straight As, the paper might spend a day under that magnet before it quietly migrated to a drawer.

“Look at our girl,” Mom would gush, tapping Amanda’s latest achievement with a manicured fingernail. “She’s going places.”

If I was in the room she might toss me a distracted, “Good job, Camden,” already turning back to whatever new shiny milestone Amanda had reached.

My father, Thomas, was the buffer between my mother’s cold indifference and my growing sense of not-enough. He wasn’t perfect—he worked long hours and sometimes forgot school events—but he made sure to catch my baseball games when he could. He helped with science projects at the kitchen table, his big hands clumsy with glue and construction paper.

Those moments were little pockets of normalcy in a house where the air always seemed to bend around my mother’s moods.

“Nice swing, kiddo,” Dad would say after a game, ruffling my hair as we walked to the car, the summer air thick with the smell of cut grass and concession-stand hot dogs.

“Think I’ll ever be as good as the other guys?” I’d ask.

“You don’t need to be as good as them,” he’d reply. “You just need to be as good as you.”

For a long time, I believed him.

When I was fifteen, Dad went on a business trip to Detroit. It was supposed to be three days. He packed his worn leather briefcase, kissed my forehead as I sat at the dining room table finishing geometry homework, and promised he’d bring back one of those ridiculous snow globes he knew I secretly liked.

He never came home.

Dad suffered a massive heart attack alone in a hotel room. I found out when I walked into the kitchen after school and saw my mother sitting at the table with the phone still in her hand, her face pulled tight in a way I’d never seen before.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, dropping my backpack.

“It’s your father,” she said, staring past me. “He’s gone.”

There was no hug. No pulling me into her chest. Just the words dropped between us like a plate shattering on the tile.

At the funeral, relatives murmured the usual things—“He’s in a better place,” “You’ll be the man of the house now”—and my mother stood rigid by the casket, Amanda clinging to her side. I stood alone near the back, fingers digging crescents into the palms of my hands, wondering how I was supposed to be the man of a house where I’d never really been seen as a son.

Our family was never the same after that.

Without Dad’s steady presence, Mom’s favoritism toward Amanda didn’t just increase; it calcified. The college fund Dad had been quietly building for me, the one he’d talked about when we stayed up late working on solar system models, mysteriously dwindled.

“Things are tight,” Mom said when I asked about it junior year. “There were expenses. Amanda’s future is very promising, and we have to invest where it counts.”

Where it counts.

I worked two jobs throughout high school. I stocked shelves at the local grocery store after classes, the fluorescent lights buzzing overhead as I faced rows of cereal boxes. At dawn, I delivered newspapers through quiet streets, the sun just starting to smear pink over the tops of houses that all looked a little nicer than ours.

My friends spent weekends at football games and movie theaters. I spent them counting tips and calculating how many more shifts it would take to pay for a semester of community college.

Meanwhile, Amanda attended an expensive private university with all expenses covered. Mom posted photos of campus tours and dorm move-in day on Facebook, captioned with things like “So proud of my girl chasing her dreams!” My name rarely appeared on her timeline unless I happened to be in the background of a holiday photo.

By the time I turned eighteen, I had just enough saved to move out and enroll in the architectural design program at Illinois State University. It wasn’t the prestigious east-coast school I’d once imagined, but when I carried my secondhand duffel up three flights of dorm stairs, it felt like scaling a mountain.

Those first months away from home were like learning to breathe again. No more walking on eggshells. No more measuring every word, every grade, every achievement against Amanda’s.

In my tiny dorm room with cinderblock walls and mismatched posters, my life finally felt like it belonged to me.

I threw myself into my studies, stayed up late sketching floor plans and elevations, my mechanical pencil smudging the edges of tracing paper. I worked part-time at the campus bookstore, shelving textbooks and ringing up nervous freshmen, slowly building a life separate from my family’s toxicity.

For the first time, I wasn’t the invisible middle child. I was just Camden, the kid who was good at design and always had a mechanical pencil behind his ear.

During my sophomore year, I met Alicia in a design theory class. She slid into the seat next to me one Tuesday, her notebook already open, a coffee cup balanced precariously on a stack of textbooks.

“Hey, is anyone sitting here?” she asked.

“Just my crushing self-doubt,” I said before I could stop myself.

She laughed, this bright, surprised sound that made my chest warm.

“Cool,” she said. “I’ll sit next to both of you.”

We became study partners, huddled over models made of foam board and glue in the studio, arguing about sightlines and natural light. We became friends, trading stories about our families, our hometowns, the versions of ourselves we were trying to grow into.

Eventually, we fell into a relationship that felt less like falling and more like coming home.

Alicia was brilliant and creative. She seemed to see something in me that even I couldn’t recognize at the time. When I doubted my talent, she’d tap her pen against my sketchbook.

“Stop tearing yourself down,” she’d say. “You’re good at this, Cam. Really good. Apply for that internship. What’s the worst they can say, no?”

She pushed me to apply for competitive internships, celebrated every small victory as if it were monumental, and sat with me through every rejection, already plotting the next step.

After graduation, we both landed entry-level positions at different architectural firms in Chicago. We rented a tiny apartment with a leaky faucet and mismatched furniture, but it was ours. The city outside our windows was loud and unpredictable, but inside those four walls there was a sense of safety I’d never felt growing up.

I proposed to Alicia on the shores of Lake Michigan on a snowy December evening. I’d spent six months saving for a modest diamond ring, skipping takeout and bringing leftovers to work, silently calculating the cost of forever in my head.

The wind off the lake cut through my coat as I knelt in the slush, my fingers numb around the ring box.

“Alicia,” I said, my breath turning to white clouds between us, “will you marry me?”

She said yes before I even finished asking.

During those early years of marriage, I made sporadic attempts to rebuild my relationship with my mother and sister. We drove out to Elmwood Park for Thanksgiving, for Christmas, for the occasional Sunday dinner where the table groaned under the weight of food and unspoken resentments.

Each gathering left me emotionally drained. Alicia would squeeze my hand under the table when Mom interrupted me to ask Amanda another question about her career, when my stories died half-formed in my throat.

On the drive home, city lights streaking past the windshield, Alicia would rest her hand on my knee.

“They’re missing out on knowing the incredible person you are,” she’d say softly.

“I don’t know,” I’d reply, staring straight ahead. “Maybe I’m just expecting too much.”

“You’re expecting basic kindness,” she’d counter. “That’s not too much.”

I wanted to believe her. Most days, I did.

When Alicia told me she was pregnant, the joy was indescribable. We were standing in our cramped bathroom, the test between us on the counter, the hum of the overhead fan loud in the tiny space.

“Cam,” she whispered, eyes shining, “we’re having a baby.”

I laughed, this disbelieving, shaky sound, and pulled her into my arms.

Later that night, I called my mother, hoping—against all better judgment—that this grandchild might finally bridge the chasm between us.

“Mom,” I said when she answered. “Alicia and I have some news. You’re going to be a grandma.”

There was a pause, just long enough for hope to flare and then sputter.

“Oh, that’s nice,” she said. “Did Amanda tell you she got promoted to senior management?”

I stared at the wall, phone pressed to my ear, the cheap paint suddenly fascinating.

“No,” I said. “She didn’t.”

Mom launched into details about Amanda’s new salary, her corner office, the way her boss had pulled her aside to say she was indispensable. I listened for a minute, then quietly ended the call.

I hung up and placed my hand on Alicia’s stomach, still flat under her T‑shirt.

“I promise you,” I whispered to our unborn child, “you will never feel the sting of conditional love. Not from me.”

Mason arrived on a rainy Tuesday in April. Seven pounds, six ounces of pure perfection. The hospital room window was streaked with water, the city outside washed in gray, but in my arms was the brightest thing I’d ever seen.

Holding him, I made a silent vow to break the cycle of emotional neglect I’d grown up with. This tiny human would know, without doubt, that he was loved, valued, and enough exactly as he was.

For the first few years, Alicia and I created the family environment I’d always yearned for. Our modest home was filled with laughter, encouragement, and genuine affection. There were bedtime stories and Saturday morning pancakes, sidewalk chalk drawings that stained our hands for days.

I took countless photos documenting every milestone—first steps on the worn living room rug, first day of preschool with a backpack too big for his shoulders—determined that Mason would have tangible proof of a childhood filled with love.

I continued inviting my mother and sister to important events: Mason’s christening, his first birthday, preschool graduation. I sent texts, emails, printed invitations addressed in my careful block letters.

Sometimes they’d show up for twenty minutes, make a cursory appearance, take a few photos for social media, and leave just before the cake was cut.

Every time, I told myself it was better than nothing.

Every time, I tucked the hurt away in the same place I’d been storing it since childhood, that quiet corner of my chest where disappointments piled up like unopened mail.

I didn’t know it then, standing in church halls and preschool classrooms, watching my mother and sister breeze in and out of my son’s life, that those twenty-minute cameos were rehearsals.

Rehearsals for the three hours my boy and I would spend alone in a decorated party room, his superhero invitation still pinned to our freezer door under a fading American flag magnet, waiting for a family who had already decided not to show up.

And now here I was, all those years of being the afterthought coiled behind my ribs while two officers stood on my porch because my mother had decided that if she couldn’t control me with guilt, she’d try fear.

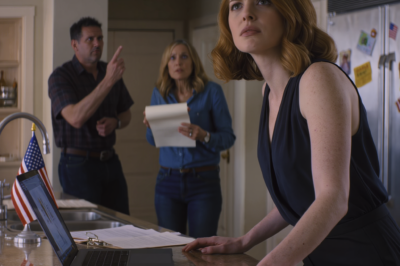

The taller officer shifted his weight, his winter jacket creaking softly. His nameplate read CALDWELL. The other, a Latina woman with tired eyes and a neat bun under her cap, was REYES.

“Like I said, Mr. Hayes,” Caldwell repeated, his tone professional but not unkind, “we got a call asking for a welfare check on your son. We’re not here to cause trouble, but we do have to follow up.”

Behind me, I could feel Mason hovering in the hallway, his Lego build abandoned on the coffee table. Sinatra’s voice floated faintly from the Bluetooth speaker, singing about strangers in the night while my past and present collided at my front door.

“Sure,” I said, swallowing the bitter taste in my mouth. “Come in.”

I stepped aside, letting them into our small living room. It wasn’t perfect—there were crayons on the coffee table, a blanket half-folded on the couch, Mason’s sneakers kicked off by the door—but it was ours. It was clean, warm, and safe.

Reyes gave Mason a small smile. “Hey there,” she said gently. “What’s your name?”

“M-Mason,” he answered, clutching the hem of his T‑shirt.

“I like your city,” she said, nodding toward the Lego sprawl on the table. “You build all that?”

He nodded once.

“That’s pretty cool.” She glanced at me. “Mind if we sit down and talk for a second?”

“Of course,” I said. “Whatever you need.”

They settled on the couch while I took the armchair across from them. Mason perched on the arm of my chair, close enough that I could feel the tremor in his leg.

“Before we get into it,” Caldwell said, resting his forearms on his knees, “I want you to know this: someone asked us to check in. That’s our job. It doesn’t automatically mean you did anything wrong. Okay?”

“Who called?” I asked, even though I already knew.

He hesitated, then sighed. “Your mother, Patricia.”

Of course.

“What did she say?” I asked.

Reyes pulled a small notebook from her pocket, flipping it open. “She reported that you’d ‘suddenly cut the entire family off,’ changed your locks, and were ‘emotionally unstable’ following a disagreement about finances,” she read. “She said she was concerned you might be isolating your son and that he might be in danger.”

My jaw tightened. The room seemed to shrink, the edges of my vision flickering with the memory of all the times my mother had called me sensitive, dramatic, ungrateful. Now she’d added dangerous to the list.

“Do you mind if we talk to Mason for a second?” Caldwell asked. “You can stay in the room, but we have to ask him a few questions.”

I looked at my son. “Is that okay with you, buddy?”

He bit his lip, then nodded.

“Hey, Mason,” Reyes said, her voice warm. “Do you feel safe here with your dad?”

“Yes,” he said immediately.

“Does he ever hurt you?”

“No.” His voice was small but firm.

“Does he ever leave you alone for a long time without anyone to watch you?”

He shook his head. “He picks me up from school every day. And when he works late, Miss Richardson downstairs watches me and we have grilled cheese.”

Reyes smiled. “That sounds pretty good.”

Caldwell glanced around the room, his gaze landing on the open doorway to Mason’s bedroom, the stack of library books on the end table, the school calendar pinned on the wall with a cheap magnet shaped like a slice of pizza.

His eyes followed the line of the wall into the kitchen, where the freezer door was visible. From where he sat, he could see the red, white, and blue of the American flag magnet and the superhero invitation curling under it.

“What’s that?” he asked, nodding toward the kitchen.

“That’s my birthday invitation,” Mason said quietly. “Dad and I made it.”

Caldwell looked at me. “Mind if I take a closer look?”

“Go ahead,” I said.

He stood and walked into the kitchen, reading the bright letters, the date from ten days earlier. The RSVP line with my mother’s name scrawled next to a little hand-drawn phone.

“You have a party recently?” he asked.

Mason’s shoulders sank. “Nobody came,” he said. “Grandma said she would, but she didn’t. Nobody did.”

Reyes glanced at me, her eyes softening.

“I see,” Caldwell murmured, coming back to the living room. He eased himself onto the couch again. “Mason, do you know why your grandma might be upset?”

“Because Dad sent her one dollar on his phone,” Mason said. “He showed me. He said we’re not going to Miami. Then he changed the locks so she can’t come in whenever she wants.”

Reyes covered her mouth for half a second, hiding what might have been the ghost of a smile.

“Okay,” Caldwell said, nodding slowly. “That helps.”

He looked at me. “Mr. Hayes, I’m going to be straight with you. We get calls like this sometimes. Family disagreements that turn into people using 911 like a referee.”

“I’ve never called 911 on anyone in my life,” I said. “But my mother decided that me finally setting a boundary is an emergency.”

“I hear you,” he said. “From what I’m seeing here—food in the fridge, a made bed in there, schoolwork, a kid who says he feels safe—we don’t have any grounds for immediate concern. We do have to file a report that we came by, that we spoke to you both, and that there were no issues observed. Depending on the protocol, a social worker may follow up with a phone call or letter, just to close things out.”

“Is this going to mess things up for Mason?” I asked. “School, anything?”

“Usually not,” Reyes said. “If anyone calls from a department, just answer their questions honestly like you did with us today. You clearly care about your son.”

Mason’s hand found mine, small fingers curling around my thumb.

“Are they going to take me away?” he whispered.

The question hit me like a punch. It was the same flavor of fear that had been in his eyes at the empty party room, packaged in different words.

“No,” I said, looking directly at him. “No one is taking you away. We’re okay.”

Reyes nodded. “He’s right. We don’t take kids away from safe homes with involved parents. That’s not how any of this works.”

Caldwell reached into his pocket and pulled out a business card, sliding it across the coffee table to me.

“If your mother keeps calling,” he said, “or if you feel like she’s harassing you, document everything. Texts, emails, whatever. If it escalates, you can talk to an attorney or come down to the station for advice on next steps. Grandparents don’t get automatic rights to override a parent’s decisions, no matter what they think.”

It was the most validating sentence I’d heard anyone in authority say about my family in thirty-four years.

“Thank you,” I said, my voice rough.

Reyes stood, smoothing her uniform. “You’re doing okay, Mr. Hayes,” she said. “I know it probably doesn’t feel like it right now, but you are. Just keep doing what you’re doing for your kid.”

They shook my hand, waved goodbye to Mason, and left. The door clicked shut behind them with the soft finality of a period at the end of a long, exhausting sentence.

For a moment, I just stood there, listening to Sinatra fade out and the hum of the refrigerator fill the silence.

“Dad?” Mason’s voice pulled me back.

“Yeah, buddy?”

“Grandma told them you were bad?”

I exhaled slowly, rubbing a hand over my face. “Grandma told them she was worried, and she used some words that weren’t true,” I said carefully. “Sometimes, when people don’t like the choices you make, they try to convince everyone else that you’re the problem.”

“Are you the problem?” he asked.

I thought of every empty chair at his party. Every disappeared college fund. Every time my mother had turned a good moment into another chapter in the Amanda Show.

“Not this time,” I said. “This time, I’m just a dad doing what he thinks is best for his kid.”

He nodded slowly, still processing.

“Will the police come back?”

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “They might call. They might not. But if anyone ever makes you feel scared, you tell me. That’s my job—to keep you safe and tell the truth.”

He seemed to accept that. A few minutes later, he was back at the coffee table, adding a bridge to his Lego city, the way kids instinctively know how to return to play even when the ground has shifted under their feet.

I walked into the kitchen and stood in front of the freezer. The American flag magnet held Mason’s invitation like it had from the beginning, the paper now slightly faded at the edges.

Ten days.

Three hours in that party room.

One dollar sent.

It’s funny how the smallest numbers can rearrange your entire life.

I traced the outline of the flag with my thumb. When I was a kid, that image had meant parades and fireworks, Dad grilling hot dogs in the backyard while the neighborhood kids ran around with sparklers. Freedom had been a word on TV, at school assemblies, in history textbooks.

Now, the magnet represented a different kind of freedom. Not the country-sized kind, but the kind you carve out for yourself when you finally decide you’re allowed to walk away from people who consistently choose to hurt you.

I thought back to the night Alicia left.

Four years earlier, there had been no police cruiser at the curb, no welfare check, no witnesses. Just the sound of a suitcase zipper and the trembling silence of a house holding its breath.

Mason was six then, all knobby knees and missing front teeth. The three of us had been orbiting exhaustion for months—two demanding jobs, a mortgage that bit harder than we’d anticipated, a child who deserved more patience than we sometimes had left at the end of the day.

The fights had started small. Whose turn it was to do bath time. Who forgot to pick up milk. Whose career should take precedence when the daycare called to say Mason had a fever and needed to be picked up.

“I can’t be everything to everyone, Cam,” Alicia had said one night, her hands wrapped around a mug of tea that had long since gone cold. “I’m drowning.”

“I’m not asking you to be everything,” I’d replied, standing at the sink, fingers pruned from washing dishes. “I’m asking you to be here. With us. We’re both tired. We’re both working. But he needs us.”

“Exactly,” she’d said, her voice cracking. “He needs two parents who aren’t constantly running on fumes. Maybe he’d be better off with one who isn’t resenting the other all the time.”

We’d gone in circles like that, our words scraping against old insecurities neither of us had fully named. I’d begged my mother to watch Mason more often so we could have a date night, a break, anything.

“I raised my kids,” she’d said on the phone, the clink of ice in her glass coming through the line. “I’m not a built-in babysitter. Besides, Amanda’s girls need me. Their school is so demanding. I can’t be everywhere.”

So Alicia and I did what millions of parents do—we pushed through, hoping the next season would be easier.

It wasn’t.

The morning she left, I woke up to the sound of a dresser drawer sliding shut. For a split second, I thought I was dreaming. Then I rolled over and saw the open closet, the empty hangers swinging like small, silent metronomes.

“Alicia?”

She stood by the doorway, a suitcase by her feet, her face pale.

“I can’t do this anymore,” she whispered.

“Do what?” My throat felt tight.

“This life,” she said. “This constant feeling like I’m failing you, failing him, failing myself. I need to figure out who I am outside of this house before there’s nothing left of me.”

“What about Mason?” I asked, the question ripping out of me. “He’s six. You’re his mom.”

She flinched. “I know. And I’m not abandoning him, Cam. I’ll call. I’ll visit. I’ll send money. But I can’t stay here and slowly disappear.”

I wanted to tell her that she didn’t have to disappear, that we could find a way to make the load lighter for both of us. But the words stuck. Years of being the one who adjusted, who made do, who took the smaller slice so someone else could have more, had worn grooves into my brain.

In the end, all I said was, “Please don’t go.”

She went.

For the first year, she called regularly, FaceTimed with Mason on weekends, sent birthday presents that arrived just on time. She did send money when she could. But distance has a way of stretching intentions thin, and eventually the calls became less frequent, the visits more sporadic.

I never told Mason she didn’t love him. I told him she’d had to move for work, that grown-up problems were complicated, that none of it was his fault.

When it got really quiet on her end, when weeks stretched into months without a call, I’d sit on the couch after Mason was asleep and stare at my phone, thumb hovering over her name.

I called my mother once, the night Alicia left.

“Mom,” I’d said, my voice shaking. “Alicia moved out. I don’t know what to do. Mason—”

She sighed heavily, like I’d inconvenienced her.

“Well, what did you do to push her away?” she asked. “You’ve always been so intense, Camden. Women don’t like feeling smothered. Amanda never has these problems.”

I pressed the heel of my hand into my eye until stars burst behind my eyelid.

“I’m asking if you can help with Mason,” I said. “Just for a couple weekends. I’m trying to sort out childcare.”

“I told you,” she replied. “I’m busy. And honestly, maybe this is a sign. Kids pick up on instability. Maybe he’d be better off spending more time with Amanda’s family. They have such a solid home.”

Any illusion I’d had that my mother might swoop in with comfort or support died in that moment.

So I found another way.

Miss Richardson from downstairs started watching Mason on the evenings I worked late. My coworker Dave swapped shifts when I got a last-minute call from the school nurse. Our neighbor across the hall, a retired firefighter, taught Mason how to ride a bike in the alley behind the building.

Little by little, blocks of support stacked themselves around us—not from the people who shared our last name, but from the ones who shared their time and their kindness.

Standing in front of the freezer now, police visit barely an hour behind us, I realized that those same people were the ones I trusted to show up if we ever needed help. Not my mother. Not Amanda. Not the relatives who liked the idea of family more than the work of it.

That night, after Mason fell asleep, I sat at the small dining table with Caldwell’s card in front of me. The city outside our window buzzed faintly—distant sirens, the rumble of the L train, someone’s TV leaking laughter through thin walls.

I opened my laptop and started searching.

“Family law free clinic Chicago.”

“Grandparent rights Illinois.”

“Documenting harassment from relatives.”

The search results weren’t exactly bedtime reading, but they gave me something I hadn’t had in a long time: information. Options.

I made an appointment at a legal aid clinic for the following week. The woman on the phone was efficient, her voice brisk but kind.

“Bring any texts, emails, or notes you think are relevant,” she said. “We’ll go over them together.”

When the day came, I took the afternoon off work, dropping Mason at an after-school program that cost more than I liked to think about but felt worth every penny.

The clinic was in a brick building downtown, American flag hanging limp on a pole outside the entrance. Inside, the waiting room smelled faintly of coffee and copier toner. Flyers about tenant rights and custody agreements papered the walls.

My attorney—really more of a volunteer consultant—was a woman in her forties named Lena. She wore a navy blazer and sneakers, her hair twisted up with a pencil.

“Tell me what’s going on,” she said, flipping open a legal pad.

I told her about the party. The empty chairs. The $2,600-per-person text about the Sweet 15 in Miami. The one-dollar Venmo. The blocks. The welfare check.

“Do you have the messages?” she asked.

I slid my phone across the table, the mass text from my mother glowing on the screen, my tiny digital “Congratulations” beneath it.

Lena read, her mouth tightening.

“And she reported you to the police after you blocked her?”

“Yes.”

She scribbled something down. “Okay. First thing: you’re allowed to decide who is involved in your child’s life. As long as your son is safe, housed, fed, in school—there’s no legal requirement that you maintain contact with extended family.”

“What about grandparent rights?” I asked. “I read something online—”

“In Illinois, grandparents can petition for visitation under certain narrow circumstances,” she said. “But the courts start from the assumption that a fit parent’s decisions are in the child’s best interest. A few missed birthdays and some hurt feelings won’t override your choices. If anything, the pattern of behavior you’ve described could work in your favor if it ever came to that.”

“So she can’t just show up with police and make me hand Mason over for a weekend?”

“No,” Lena said firmly. “If she keeps calling 911 for non-emergencies, that can become a problem for her, not you. That’s why it’s important to document. Save everything. If she escalates—shows up at school, contacts your employer, spreads rumors that impact your housing—we’ll have a paper trail.”

Housing.

The thought made my stomach lurch. I pictured my landlord, Mr. Patel, standing in the hallway as the police walked past him to my door.

“Everything okay?” he’d asked after they left, his accent wrapping around the words.

“Family drama,” I’d said, shame prickling the back of my neck.

“In my experience,” he’d replied, “no one does drama like family. Your rent is on time. Your kid says hello every time he sees me. That’s what matters here.”

I held onto that like a lifeline.

“I can’t promise you there won’t be more waves,” Lena said, closing her folder. “People who are used to you having no boundaries rarely applaud when you grow some. But legally? You’re on solid ground.”

On the way home, I stopped at a dollar store to pick up milk and dish soap. At the end of an aisle, a rotating rack held rows of cheap magnets—smiley faces, state shapes, tiny flags.

My hand hovered over a fresh flag magnet, identical to the one on our freezer.

I almost bought it.

Then I reached for a different one—a simple blue rectangle with white letters that said, in a cheerful font, “HOME IS WHO YOU LOVE.”

It cost ninety-nine cents.

That night, after dinner, I stood in front of the freezer again. The old flag magnet still held Mason’s superhero invitation in place. I moved it carefully, sliding it up to the corner of the door, and pinned the invitation under the new magnet instead.

Mason wandered in, toothbrush hanging from his mouth.

“New magnet?” he asked around the foam.

“Yeah,” I said. “Figured it was time for something different.”

He squinted at the words, sounding them out. “Home is who you love.”

He smiled, toothpaste on his lip. “That’s us.”

“Yeah, buddy,” I said. “That’s us.”

The old flag magnet stayed on the door, but its job had changed. It held up a grocery list now, coupons for canned soup and laundry detergent. Necessary, but not sacred.

A few days later, the ripple effects of the police visit reached Mason’s school.

When I arrived at pickup, Ms. Diaz, his fourth-grade teacher, pulled me aside.

“Is everything okay at home?” she asked gently. “Mason mentioned the police came by.”

Heat rushed to my face. “We’re fine,” I said quickly. “My mother… called in a welfare check because I set some boundaries she didn’t like.”

Ms. Diaz nodded like she’d heard a version of that sentence before.

“He told me you changed the locks,” she said. “He said it like it was a big deal, but a good one.”

“It is a big deal,” I said. “For both of us.”

She smiled. “If you ever need any documentation from us—you know, about his attendance, his progress, anything that shows he’s doing well—just ask. Sometimes having that helps.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it.

On the walk home, Mason kicked at a pile of leaves, his backpack bouncing.

“Some kids saw the police car,” he said. “They asked if I got arrested.”

“What did you tell them?”

“I said no,” he answered. “I said my grandma made a bad choice and the police had to tell her we’re okay.”

I swallowed a laugh. “That’s… not inaccurate.”

“Am I in trouble at school?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “You’re doing great at school. None of this is your fault. None of it changes how smart you are, how kind you are, or how proud I am of you.”

He mulled that over for a few steps.

“Can we have another birthday party?” he asked suddenly.

My heart twinged. “Another one?”

“Not with them,” he said immediately. “With our people.”

“Our people.”

I thought of Miss Richardson, of Mr. Patel, of Ms. Diaz, of Dave at work. Of the neighbor kids who always waved at Mason on the stairs.

“Yeah,” I said. “Yeah, I think we can do that.”

We didn’t have the budget for another rented party room or a custom cake. But we had a small backyard behind our building, a grill that still worked, and a community of people who had already shown up when it mattered.

So I made a list.

The next Saturday, I stood at the same kitchen counter where I’d once filled goodie bags for an empty party room and wrote a new invitation.

“MASON’S LEVEL-UP GAME NIGHT,” it said at the top in big, uneven letters. “Pizza, board games, backyard s’mores. No presents, just you.”

I let Mason decorate the edges with little drawings—dice, controllers, stick-figure superheroes.

We made copies at the library. I handed one to Ms. Diaz at pickup, one to Miss Richardson downstairs, slipped one under Mr. Patel’s door, and texted a photo of it to Dave at work along with, “Only if you promise not to beat the kids at Mario Kart.”

The original went up on the freezer door.

The “Home is who you love” magnet held it in place.

The flag magnet pinned the corner, like a backup singer who’d finally accepted he wasn’t the star of the show.

The night of game night, the air was just warm enough to sit outside with jackets on. String lights we’d borrowed from Miss Richardson zigzagged across the backyard fence, casting a soft glow.

But the real light was the sound.

Kids’ laughter. Adults talking. The crackle of a small fire in the portable fire pit that Mr. Patel had insisted on bringing down from his storage unit.

People came.

They came early, arms full of soda and chips and a store-bought sheet cake that didn’t have any custom frosting but tasted like the best thing I’d eaten in months.

Ms. Diaz arrived with a stack of board games and a bag of extra gloves “just in case someone’s hands get cold making s’mores.”

Dave showed up in a vintage Bulls hoodie, his wife and two kids in tow.

“I brought reinforcements,” he said, handing Mason a new pack of trading cards. “Couldn’t let you play Monopoly with only your dad. He cheats.”

“I do not cheat,” I protested.

Mason grinned, the shadows under his eyes from the last few weeks finally softening. “You kind of do,” he said.

Later, as the kids crowded around the TV in the living room for a Mario Kart tournament, the adults gathered near the grill.

“So,” Dave said quietly, nodding toward the invitation still visible through the sliding glass door. “How are you doing? Really?”

I hesitated, then shrugged. “Angry,” I admitted. “Relieved. Guilty for feeling relieved. Tired.”

“That tracks,” he said. “Family can mess you up like nothing else. But look.”

He pointed toward the living room, where Mason was wedged between two neighbor kids, shouting with joy as his character zipped around a bright digital track.

“That kid is loved,” Dave said. “Whatever your mom thinks, that part’s not up for debate.”

I looked at Mason, at the way he leaned fully into the moment, at how quickly children can rediscover joy if you give them a safe place to put it.

“Yeah,” I said quietly. “He is.”

My phone buzzed in my pocket.

An unknown number.

For a second, my stomach flipped. Then I pressed the side button and let it ring out.

Later, I saw there was a voicemail. I listened to the first few seconds in the kitchen while the kids argued over who got the next turn.

“Camden, it’s your mother,” the voice began, sharp even through the tiny speaker. “I cannot believe you—”

I hit delete.

I didn’t need to hear the rest. I knew the script by now.

Instead, I walked back outside, where Mason was roasting a marshmallow with the intense focus of a scientist.

“Careful,” I said. “You’re about to set it on fire.”

“That’s the best part,” he argued.

He pulled the marshmallow from the flame just before it ignited, golden and perfect.

“Make a wish,” Miss Richardson teased.

He closed his eyes for a second, then opened them and took a bite.

“I already got it,” he said, mouth full. “People came this time.”

I felt something in my chest unclench, an old wound easing just a little.

After everyone went home and the last paper plate was thrown away, I tucked Mason into bed. He was half-asleep before his head hit the pillow, sugar and laughter finally catching up with him.

“Dad?” he mumbled as I pulled the blanket up to his chin.

“Yeah?”

“Do we have to invite Grandma to stuff anymore?”

I sat on the edge of the bed, running my hand through his hair.

“No,” I said. “We don’t have to invite anyone who keeps choosing to hurt us. Family is supposed to make your world bigger, not smaller.”

“Okay,” he whispered. “Good.”

He drifted off, his breathing evening out.

In the kitchen, I stood in front of the freezer one more time. Two invitations now, one slightly faded, one new. Two magnets holding them in place.

The old flag, edges chipped.

The new rectangle with its simple truth.

Home is who you love.

My phone lay silent on the counter. No new calls. No new texts.

For the first time in a long time, that silence didn’t feel like a punishment. It felt like space. Room to build something better.

I didn’t know what would happen with my mother and sister. Maybe there would be more calls, more attempts to pull us back into their orbit. Maybe there would be long stretches of nothing at all.

But I knew this: the next time my son asked, “What’s wrong with me?” I’d have more than words. I’d have nights like this one to point to—photos of him surrounded by people who chose him, laughter echoing off the walls of a small Chicago home.

I’d have a freezer door covered in proof that we had built a new story.

And every time I reached for the handle, my fingers brushing that flimsy American flag magnet, I’d remember that I’d finally done the thing my father never got the chance to do.

I’d stepped out of the shadow of someone else’s version of family and into my own.

Not with fireworks or parades.

Just with a changed lock, a one-dollar message, and a quiet decision that my son and I were worth more than empty chairs.

In a country where people love to talk about freedom, I’d found mine in the smallest, most ordinary place.

Right here, in this little kitchen, under the soft buzz of a tired light bulb and the steady hum of a refrigerator holding two invitations to a life my mother would never understand.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load