Hannah’s forehead strip shouted 104° F in angry red, and for a heartbeat I believed if I stared long enough the digits would blink and roll backward, a slot machine mercifully spitting cherries instead of danger. The nursery smelled like talc and milk and that warm, innocent scent babies carry like a passport to every soft part of an adult. In my arms, my daughter burned.

“I’m calling the pediatrician,” I said. My voice tried to be that calm, steady tone I imagined good mothers used, the kind that untangled emergencies by willpower alone.

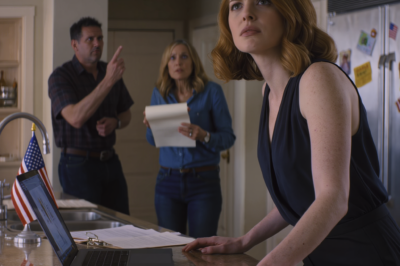

“Wait, Natalie.” Ethan didn’t look up from the blender. The kitchen was five steps from the nursery in our small, close‑walled house, and the whir of blades made the whole place feel like it was vibrating. A brownish liquid spun in the glass pitcher—one of those thick, dense smoothies his mother loved. “Mom has an herbal mix. Worked better than any meds when I was a kid.”

Barbara stood by the counter with the proprietary smile of someone who confuses family recipes with peer‑reviewed science. “You panic too much,” she said. “You can’t give a baby a pill every time she gets warm. Nature heals. That’s how we do it.”

Hannah pressed her hot face into the curve of my neck and made that soft, high whine that means everything in her little world is wrong. My brain ripped between instincts: do something now / don’t make a mistake / be firm / don’t offend / fix this. I pulled open the child‑safety latch and took out the acetaminophen our pediatrician had recommended. Tylenol, grape flavor, infant drops. Dose by weight; we’d reviewed it at her last well‑visit. I could still hear Dr. Patel’s nurse, brisk and kind: by weight, not by hope.

Barbara touched my elbow with fingers that felt like a claim. “Let’s try a compress first,” she said. “I’ll make one. You don’t want to poison the baby with chemicals, do you?” She said chemicals the way people say betrayal.

Lily was on the rug with her magnetic tiles, the tower taller than her bent knees, her small face intent in that seven‑year‑old way that looks like prayer. She glanced up at me, then at the medicine in my hand, then back to me again. A flicker crossed her face, a shy animal before a thunderclap.

“I’m calling the office anyway,” I said, already dialing. The practice voicemail was the steady voice of a lifeguard: for a baby over 3 months with a fever over 103° F, or if the baby seems very tired, won’t drink, or has trouble breathing, call 911 or go to the ER.

I pressed the option for the on‑call nurse. “This is Natalie Miller,” I said when she picked up. “My daughter is eight months old, 104° F, hot and fussy, drinking poorly.” The words fell out clipped and square because fear had sanded every curve off my voice.

“Acetaminophen by weight now,” the nurse said. “Watch closely. If there’s no drop within an hour, or if she gets more listless, go to the ER. No mixing meds with herbs or honey. No home remedies.”

I hung up and said it out loud: “Acetaminophen.” Saying it gave me a little shield against doubt.

Barbara made a face. “Phone advice,” she said, as if phones were superstition. “In my day, mothers knew better. Here’s a compress. And here’s bark tea. It brings the fever down gently. Natalie, you’re a mother. Don’t be a robot.”

“I am a mother,” I said quietly. “And I’m doing what the doctor said.”

I measured the Tylenol with hands that wanted to shake and lifted Hannah’s head. She swallowed and grimaced, her lashes sticking to her damp cheeks. I pressed my cheek to her hair. Heat radiated through my skin like a warning.

“Cold juice will make it worse,” Barbara muttered. “Modern pediatrics goes to extremes.”

I didn’t reply. I watched Hannah breathe—fast, uneven, but steady—and listened to the kitchen whispering behind me. Ethan’s shadow and Barbara’s shadow made a single outline in the doorway, two solid shapes that believed the world worked the way it used to.

I set a forty‑five minute timer. I set a second one in my head.

An hour later the strip read 103.6° F, a not‑enough mercy. Hannah’s body lay heavy on my chest like she’d traded her bones for sand. She dozed and jerked with heat, a tiny boat fighting choppy water. My gut said we were losing, and the worst part about losing is that you often don’t see the score until the clock runs out.

I typed 9‑1‑1, hovered, and bargained with myself for thirty more minutes. If the curve didn’t slide down, we would go. The house held its breath. In the kitchen, plastic bags rustled. Barbara poured something with the slow care of ritual. Lily went for water, disappeared down the hall, then returned and tucked herself into the couch with her knees under her chin.

“Mom,” she whispered. “Grandma said she’s making a healthy syrup for Hannah. Don’t be mad.”

“I’m not mad,” I said, while my heart gripped itself. “I’m doing what the doctor said.”

I took another temperature. 104.2° F. Forget thirty minutes. I hit call.

“911,” the dispatcher said, neutral as a horizon.

“Eight‑month‑old,” I said. “One hundred four degrees. We gave acetaminophen by weight. She’s breathing. Drinking a little. She’s very hot and fussy.”

“Stay on the line. Help is on the way.”

I nodded to no one and told myself only this: Keep crying, baby. Cry means energy. Cry means you’re still fighting.

Barbara burst in. “Why call 911? We can handle this. I put good bark syrup in a bottle. It brings the fever down.” She held up a seltzer bottle, a thin amber ring marking where liquid had been.

Something clicked in my head with the exact sound of a lock turning. “Put it away,” I said. “Ethan, get the bag. Blanket, diapers, insurance card, my wallet.”

“Natalie,” he said, dazed, as if he’d stepped from one reality to another too fast and the light had gone strange. “If they come, they’ll just say to give medicine.”

“We did,” I said. “And we’re going.”

The siren wailed before I finished dressing Hannah. The paramedic who took the lead wore a ponytail and a badge that read ABBY. She knelt and checked Hannah’s pulse and breathing, pressed a hand to the little rise of ribs under the onesie. “How long has the fever been this high?”

“Since this morning,” I said. “We gave acetaminophen. Grandma made some herbal stuff.”

“What exactly?” Abby asked, looking at Barbara.

“Plants,” Barbara said, the syllable flat with defensiveness. “Chamomile, willow bark, a little honey. Natural.”

“No honey under one,” Abby said, clean and sharp. “And willow bark has salicylates—aspirin‑like—not for infants.” Her eyes were kind but unequivocal. “We’re going to the ER. Bring every bottle and powder you’ve given.”

Barbara pressed her lips together. For a split second something scuttled behind her eyes, like a bug caught in bright light.

Lily looked up at me, her face serious in the way of kids who want to be useful and fear they might not be. I tucked her under my arm as if I could shield her from words.

The ER was metal and plastic and speed. A nurse clipped a pulse ox to Hannah’s toe; a tech drew labs with a calm so practiced it felt like music. A doctor introduced herself as Dr. Patel and asked short questions in a rhythm that made them easier to answer. “When did it start? What did she take? What did she drink? Any allergies? Vomiting? Seizures?”

I answered in small, square yeses and nos. Barbara stood with her jaw out and her chin up, the posture of someone on a rooftop waving off the ladder.

“We treated each other naturally,” she said finally. “My mother used these remedies forever.”

“We need the actual ingredients,” Dr. Patel said, calm but immovable. “We’ll test blood and urine. Please hand over any bottles you brought.”

Ethan stood with his hands locked together the way a kid does outside a principal’s office. We were three adults and one tiny furnace whose skin smelled like milk, sweat, and prayer.

A nurse returned with a woman in a plain cardigan whose presence quieted the room in the way of someone used to walking into moments that teeter. “I’m Ms. Kim, the social worker on tonight,” she said. “This is routine. With high fevers in infants, we check the home picture. We’re here to help. Our job is the baby’s safety.”

I nodded, grateful and terrified at the same time. Barbara turned toward the window as if the glass would take her side. Ethan whispered something I didn’t catch. She waved him off with a little slap of air.

Forty minutes later Dr. Patel returned. “Fever down to one‑oh‑one point eight with meds,” she said. “Her breathing is softer.” A stone I hadn’t realized was welded to me shifted an inch. “Labs show salicylates—likely from willow bark. In infants that carries risks from stomach irritation to more serious effects. Also, honey before twelve months can cause infant botulism. So that’s a hard no.” She looked at me and softened her tone. “I’m not judging. I’m informing. It matters.”

Barbara snorted. “Kids grew up on honey and herbs. Now doctors make everything scary.”

“We also see you dosed acetaminophen correctly,” Dr. Patel said, turning back to me. “That helped. But someone gave other things. Given the lab and the age, we’ll make a report to Child Protective Services. It’s protocol, not punishment. They’ll decide if there was a risk. Hannah will stay overnight for observation.”

Lily’s hand tugged my sleeve. She mouthed, Mom, can we talk?

“One second,” I whispered, throat tight.

In the hallway, under harsh light, Lily pulled her kid tablet from her little crossbody bag. Her hands shook. She opened Photos. A picture of our kitchen counter. The pink‑cap medicine cup. The seltzer bottle. A dropper held over the Tylenol cap, amber drops falling in.

“I saw it,” she whispered. “Grandma said it would be more helpful and that we shouldn’t tell you because you’re nervous. I took pictures. Mom, did I do the right thing?”

A cold wave ran from the top of my head to the soles of my feet. Not fear—clarity.

“You did the right thing,” I said, cupping her cheek. “You helped your sister. You helped me.”

We went back in. “We have photos,” I said. Ms. Kim gave me a secure upload link. Dr. Patel looked like a puzzle piece had just clicked. “Thank you,” she said. “That helps us understand.”

Ethan went pale. “Mom, did you—”

“I wanted to help,” Barbara flared. “You’re making a mountain out of nothing. These agencies—I am family. I was healing. Doctors sold out to pharma.”

“No one is accusing you of malice,” Ms. Kim said, steady as a metronome. “We’re talking about outcomes. You are not a legal guardian. You cannot alter a prescribed course of care.”

“This is my house,” Barbara snapped at me. “I let you live here during the renovation. I get a say.”

“Hannah has a right to be safe,” I said, my voice low but finally solid. “And I have a right to follow our doctor. That’s not up for debate.”

Ethan offered to take his mother to Aunt Mary’s. I didn’t argue. The quiet that followed them felt like a room righted after a picture has been straightened on the wall.

Ms. Kim sat beside me. “Do you want a no‑contact order between Grandma and the baby while we investigate?” she asked. The words were terrifying and liberating at once. The world simplified itself: unsafe goes out.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

She helped me sign the forms. It felt like signing more than paper—like a contract with myself: Don’t bend where it’s dangerous.

The night in the ER was long but steady. Hannah slept. Her body was a child’s again, not a furnace. I listened to her breath and the soft shuffles of machines and felt a kind of sober gratitude that had no room for gloating or grief, only relief.

We left Lily at home with Mrs. Rivera next door; at midnight my phone pinged with a single lightning‑bolt emoji, our private “we’ve got this.” I sent a heart back and, for the first time in hours, exhaled all the way to the bottom of my lungs.

In the morning Dr. Patel discharged us with strict instructions: Tylenol by weight, lots of fluids, temperature checks, pediatrician follow‑up in two days. Ms. Kim confirmed CPS would call within twenty‑four hours and that the temporary no‑contact order was active.

Home was quieter. Not safer, not yet, but quieter. No Barbara. No blender. No voice asking me to doubt what my eyes could see.

Near sunset Ethan came back looking older in the way of someone who met consequences for the first time and didn’t like their handshake. “I took Mom to Aunt Mary’s,” he said, staring at the floor. “They think you started a witch hunt.”

“I started protecting a baby,” I said. “Name it how you want.”

“It was a mistake,” he said. To me, to himself, to the air. “She didn’t mean harm.”

“Harm doesn’t need to mean itself to do damage,” I said. The sentence tasted like iron. He sat and put his hands over his face. For a second I saw the Ethan I married—kind, soft, nervous the day I learned to drive on the freeway. Then I saw a father who stood by while his mother adulterated our baby’s medicine. My focus clicked back into place.

“I’m filing for a protective order,” I said. “And a custody plan that says Barbara has no access without me present. If you’re against that, say so now.”

“I need time,” he whispered. “It’s a lot.”

“I don’t have time,” I said, looking at sleeping Hannah. “I have a child.”

CPS came the next day. A calm woman with a notepad asked about routines, food, vaccines, where we store meds, who has keys. I showed her the medicine cabinet, the fridge, the cribs, the car seats. Lily colored at the table, pretending not to listen.

“Did you take these photos?” the worker asked Lily gently.

Lily nodded, brave and small. “Thank you,” the woman said. “You helped your sister a lot.”

After they left I wanted to fall into bed and sleep a week. Instead I called a family‑law attorney whose card I’d picked up at the pediatrician’s office months ago—one of those little practical acts that felt paranoid then and reasonable now. She listened and said, “You’re doing the right things,” and set an appointment.

The police reached out next. They took statements. The lab would test the contents of the home syrup and the Tylenol cap. Weeks later the report would say what we already knew: the syrup had a high concentration of salicylates, essential oils, and sugar; the Tylenol had contaminants that had no business there. Barbara would be cited for child endangerment and interference with prescribed care. I would not cheer. Adults answer for what they do with other people’s kids, even if they’re family.

Ethan unraveled in slow motion, like a sweater whose loose thread you try not to see. He called, came by, asked me to let it blow over, to not go to extremes. I kept saying one thing: safety first, then the rest. With my attorney I drafted a temporary plan: 50/50 on set days; Grandma zero contact. The document was thick with legal lines. To me it said a simple thing: my boundaries exist outside my head.

Hannah bounced back fast, the way babies do when you take the rocks out of the road. She smiled at the phone camera, reached for toys, bossed us around with tiny, imperious hands. I counted every small win: her damp palm on my collarbone, a long nap, a grin after oatmeal.

Lily grew more serious in the steady, dignity‑soaked way of a child who did the right thing alone in a room. I booked a few sessions with the school counselor. Play and talk. She came home with stickers for honesty and care and stuck them on the fridge like medals.

One night she asked, “Mom, do you still love Grandma?”

I answered honestly. “I love our safety more than anyone’s hurt feelings. Love without rules isn’t love. If Grandma learns the rules one day, we’ll see. For now, no.”

Lily nodded. Sometimes her nod pinched my throat because it looked so adult.

Ethan spent a lot of nights at Aunt Mary’s. Between us hung long pauses, good places to store words like for now and if. He wasn’t a monster. He was his mother’s son. For the moment, that was all I needed to know.

A month later the police lab called. Results confirmed high salicylates in the syrup, plus traces in the Tylenol. There would be a hearing. My attorney handled filings; I handled the ordinary glory of a calm day: daycare drop‑off, work, dinner, bedtime, three books in a row because Lily pretended not to notice I always gave in at the third.

I emailed our pediatric practice a thank‑you for the firm line I’d heard twice that night—no honey before one. That sentence had been a railing in a dark stairwell.

The same afternoon Lily brought home a drawing. A house with three stick figures inside—me, Lily, and Hannah. Outside, a tall fence and a sign on the gate: by invitation only. I taped it to the fridge under the honesty stickers.

“It’s not because we’re mean,” she said.

“It’s because it’s right,” I said.

Spring pushed its way into the bones of the year. The court signed a longer custody plan and a temporary no‑contact for Barbara with review in a year if she completed therapy and made formal amends. Ethan stared through the paperwork like it was a fog that might become a mountain if he blinked wrong. Then he signed. We both cried—quiet, ugly, grateful tears. Sometimes an ending isn’t a slammed door; it’s a long seam sewn while you’re still awake.

Life lined itself into a pattern you can follow: daycare, Zoom meetings, chopping onions, laundry, story time. Tiny joys set the weather. A new throw blanket. A sticky berry cup. Lily’s silly kitchen dance. Hannah’s giggle when I peeked around the fridge.

I found my voice again—not the one that explains, the one that says no. We started volunteering on Saturdays, assembling food boxes in a church gym that smelled like bleach and donuts. A woman named Susan, hair in a scarf, laughed through four kids worth of chaos and said a sentence I wrote down: “Boundaries aren’t a wall against love. They’re a door with a lock.” I thought a lot about my doors.

One evening Lily came to me with her tablet. “Mom, I deleted the photos,” she said. “They did their job. I don’t want them in my head.”

“You’re smart,” I said, pulling her close. “Thank you for saving your sister and me.”

December came quiet and, for the first time in a long while, unafraid. We put up a small fake tree and paper stars. On top, Lily taped a cardboard lightning bolt—our sign for truth. We baked cookies. The kitchen smelled like vanilla and cinnamon and a home that had forgiven itself for hoping.

Barbara didn’t call. Ethan texted a short “Merry Christmas” and a photo of the toy Hannah loved at his place. We agreed he’d visit for one hour. No Barbara. He came, sat, watched, left gifts, didn’t test the rules. It was the best present he gave us all year.

After the girls fell asleep, I poured milk and scrolled my notes. At the top sat the line I wrote that night: 104° F. Tylenol. 911. ER. I thought how easily we could have slipped into a different life, how thin the line is and how it holds if someone says no at the right time.

I wrote Lily a note and slid it under her pillow. Thank you for telling the truth. That’s a superpower.

In the morning she walked into the kitchen with the note in her hand and smiled not like a little kid, but like a person who knows their heart. “Mom, can I put another drawing on the fridge?”

“Of course,” I said.

She drew our house—us inside. Outside this time wasn’t a fence; it was a garden, and by the gate she drew a tiny doorbell. She printed in careful letters: People who choose safety live here.

I taped it next to the lightning bolt and the stickers. Sometimes “American rules” are just human rules where kids come first. They’re not loud. They don’t need a pledge. They’re one thing: do no harm. If someone can’t handle that, we have doors with locks, phone numbers, and the word no.

That evening Hannah’s forehead felt warm again—teething, 100.4° F. I gave acetaminophen by weight, we put on a cartoon, and she fell asleep on me with her tiny hand resting on my chest. Lily covered us with a blanket like a guardian making a ritual.

“Mom,” she whispered, “we’re okay. We have a plan.”

We did. And having a plan didn’t mean we’d survive at any cost. It meant we would live by our rules and not hand them away.

In the weeks after, every system around us felt less like an enemy and more like scaffolding we could lean on without apology. Our pediatrician’s office called to check on Hannah and to schedule her follow‑up; the nurse’s voice had that practical kindness that makes you feel like you’re not a burden for needing help. The CPS worker emailed a list of parenting classes that weren’t punitive so much as pragmatic—how to set boundaries with extended family, how to talk to kids about safety in language that doesn’t turn the world into a haunted house.

We didn’t add any of it to our story; we just kept the parts that fit. Lily went twice to the counselor and then announced she was finished. “I want to draw instead,” she said. That was fine. Her drawings developed doors in unexpected places—birdhouses with bells, castles with knockers and little welcome mats. She drew keys everywhere. On evenings when I was tempted to spiral into the loops of old arguments—What if I’d… Should I have…—I’d look at her paper cities and breathe. We were building.

When the weather warmed, Hannah started insisting on standing, legs locked, chin high, the general of the hardwood floor. She babbled in syllables that were less word than conviction. She’d plant one hand on my shoulder and one on the coffee table and announce a future only she could see. Somewhere inside my chest, a stubborn little flag rose and unfurled.

Ethan kept to the schedule. We exchanged our daughters at the front door like diplomats. He tried hard, I could tell—the careful buckle of a car seat, the texts that confirmed nap times, the photos he sent from the park. Love can be sincere and still not be safe. I learned that truth without malice. On good days, he learned it too.

Barbara stayed silent. I didn’t stalk her online or ask Aunt Mary for updates. Boundary isn’t a synonym for curiosity. It’s a practice of attention—to the home you are building, to the children whose bodies run on the fuel of your steadiness. On the mornings I missed the fantasy of a soft, doting grandmother, I let the ache pass through and then made oatmeal.

The day the letter came about the hearing, I poured coffee and read the lines twice. Temporary no‑contact continued, review set for a year from issuance with requirements attached: therapy, parenting education, formal amends. The paper was almost boring in its bureaucracy. Maybe that was the point. Safety shouldn’t be a spectacle. It should be a form.

On the drive to daycare, Lily asked from the back, “Is a rule still a rule if someone doesn’t like it?”

“It is if it keeps people safe,” I said. “Rules that keep us safe don’t need permission.”

She was quiet for a while. “Then I think we have good rules.”

At pick‑up, her teacher handed me a slip: Character Award—Honesty. A circle of glitter glue framed her name. I waited until we were home to tell her. She danced her way from the couch to the fridge and taped the certificate next to the lightning bolt. Hannah clapped along because clapping is contagious and joy likes witnesses.

That night, when the house finally settled, I stood by the fridge and read the gallery we’d made: the bolt, the gate with the doorbell, the gold star of honesty, a grocery list with bananas circled twice because Lily had recently discovered smoothies, the custody calendar clipped in a neat grid that, despite everything, felt like grace.

I thought about the first minute of our emergency, the blender spinning, the red numbers screaming, the pull of old patterns that don’t care whether they’re right, only whether they’re familiar. I thought about the small, hard choices that are the opposite of dramatic—the ones you make with a phone in one hand and a baby in the other. 911. ER. No.

I’m not a hero. I am a mother. The distinction matters because heroes act for crowds and mothers act for rooms. I chose a room with two daughters in it and a door with a lock. When Lily whispered, “I know who did this,” she wasn’t burning a bridge; she was pointing to the map. That night—and every calm morning after—our map became readable.

The story people tell about “American parenting” is noisy: debates and hashtags and a thousand performative takes. Our house told a quieter story. It said, Children first. It said, Take the medicine as directed. It said, No honey before one. It said, Don’t mix aspirin into a baby’s bottle and call it love. It said, If you do, there are numbers we dial and forms we sign and doors we lock. And the world, imperfect and clogged with its own noise, will send a woman named Abby with a ponytail and a pulse oximeter and a voice that does not shake.

If you want to know what changed us, it wasn’t punishment. It was clarity. A fever stripped the varnish from our habits. What remained was the grain of who we were when no one was watching: a girl with a tablet and a lightning bolt emoji; a baby whose body, given half a chance, knew how to cool itself; a mother who said a small, unglamorous no. Somewhere farther out, a grandmother staring at a year that would either soften or harden her. Somewhere between, a father standing at the gate, learning what belonging looks like when safety isn’t optional.

I tucked the girls in and turned off the light. In the darkness, I could hear Hannah’s soft breath, the whisper of Lily rolling over, the slight creak of the house settling, as if the beams themselves were releasing a breath they’d held for months. The lightning bolt on the fridge would still be there in the morning, and the doorbell on the gate would still ring for the people who chose us with our rules attached.

The title of our life wasn’t dramatic once the crisis passed. It was simple enough to write on a Post‑it: We have a plan. We keep the plan. We keep the kids safe. And when someone says it’s just teething, or you’re just panicking, or nature will fix what it broke, I will look at the thermometer, at the dose by weight chart, at the numbers I know by heart, and I will answer with the quiet that built us: “I’m the mother. We’re okay.”

I used to think fevers were numbers and numbers were simple. Then I had daughters, and a number like 104° F became a sentence with a hundred clauses—some implied, some shouted. In the days that followed, after sleep began to act like itself again and our house learned the shape of quiet, I kept circling back to small details from the night that cracked us open and remade us. Not to relive the panic. To understand the hinges—what swung, what held.

There was the way Hannah’s breath sounded before the acetaminophen: fast, ragged, almost like a tiny animal trying to outrun a shadow. There was the way her breath sounded after: still quick, but easing, like a metronome someone turned down a notch. There was the rubbery tug of the pulse‑ox cord on her toe, the soft, lavender plastic of the hospital crib rails, the squeak of the curtain rings when a nurse came by to check the monitor.

And there was Lily, who kept climbing onto the vinyl chair next to me, legs folded under in a posture she must have learned from me without my noticing. She didn’t make speeches about bravery or ask for praise. She watched. She held my water cup when my hands shook. Every now and then she pressed her shoulder into my arm in a way that said, I’m here, keep going.

I used to think the difference between panic and parenting was a matter of tone—how calm you sounded when you dialed a number or measured a dose. Now I think it’s a matter of direction. Panic runs in circles and eats its tail. Parenting picks a line and walks it even if your knees wobble. That night, the line had numbers on it—15 pounds on the scale at last check, 2.5 mL in the syringe, check again in 45 minutes, call 911 if the strip climbs instead of falls. The line had words too—No honey before one. No salicylates for infants. Follow the doctor’s plan. Don’t let nostalgia borrow your child’s body for experiments.

In the ER, time stuttered and smoothed in alternating bands. A tech asked me to spell Hannah’s full name twice—“H‑A‑N‑N‑A‑H?”—as if the repetition itself were an antiseptic. Dr. Patel’s questions were tight little boxes I could drop my fear into: when did it start, what did she take, any vomiting, any seizures. Ms. Kim slid in and out like a tide, leaving behind forms and steadiness. Even the machines had manners. The monitor beeped in a polite, relentless way, not alarmed so much as present. Abby—the paramedic with the neat ponytail—stayed just long enough to hand off, to say again, “No honey, okay? You did the right thing,” and to vanish back into the night where other sirens called.

The thing about protocol is that it makes room for you to feel everything and still do the next right step. When Ms. Kim said the words no‑contact order and investigation, a part of me wanted to fold up like a paper house in rain. Another part—older than fear—sat a chair upright in my chest and took out a pen. If you have never signed a boundary in ink, you might think the pen is for defense. It isn’t. It’s for love.

Back home, I kept the thermometer on the counter for a week like a witness. Not because I expected another crisis to walk in uninvited, but because the number had taught me something I didn’t want to forget: the body tells the truth in quantifiable ways. My job was not to argue with it in poetry. My job was to listen and act.

On the second morning after the ER, Hannah laughed at a spoon for an unreasonable amount of time. Babies have an unparalleled gift for forgiving the world in chunks. She forgave the night. She forgave the beeps and the needle and the cold stethoscope. She forgave the way I’d cried soundlessly into her hair when the fever line finally bent downward. Her laugh arrived like weather—sun after fog—and soaked the kitchen.

I held that sound like a talisman when I called the attorney. The voice on the other end did not raise or lower. It made room. We reviewed what I already knew I would ask for: clarity on who may alter care, clarity on where Hannah’s body begins and ends relative to other people’s beliefs, clarity on how to keep our home from sliding back into the old habit where “help” could mean anything anyone needed it to mean. Paper is not magic. But paper changes what a person can pretend not to understand.

Ethan came by in the afternoons to see the girls. Sometimes he stood on the porch for a minute longer than was strictly necessary after I opened the door. We were very polite with each other, the way people are when they are guarding two kinds of tenderness: the tenderness you feel for the person you once loved, and the tenderness you must reserve for the children who came of that love. He brought diapers once, unasked, the big box with the handle. Another time he returned the thermometer I hadn’t noticed he’d carried out with him that night—care and habit confused still. We practiced being the new kind of us, which is another way of saying we practiced not bleeding on the kids.

If you had asked me the year before what I feared most as a mother, I would have said something cinematic—car accidents, strangers, headlines. But the danger that tried to make a home in my kitchen that day didn’t wear a mask. It wore family. It wore the cadence of “we know better because we’re older.” It wore the softness of a smile that said, Trust tradition over math.

Tradition is a comfort until it isn’t. Then it asks you to choose between peace and safety and insists they are the same. They aren’t. Peace without safety is an expensive illusion purchased with someone small.

On the third afternoon after the ER, Lily pulled the step stool to the sink and washed grapes like she was baptizing them. “Do you think Grandma will be mad forever?” she asked without looking up. The faucet made a thin silver curtain. Her hands moved under it deliberately, little palms flipping the fruit so each glossy orb took its turn under mercy.

“I think Grandma is very sure she was helping,” I said. “And sometimes when people are very sure they’re helping, it takes a long time to notice they weren’t.”

“How long?”

“As long as it takes,” I said, because some answers should teach patience and not theater.

She nodded, set the grapes in a bowl, and lined the paper towels up like a runway for them to land on. “We can wait,” she said, with the authority of seven.

Waiting didn’t mean pausing life. It meant anchoring it. We anchored with small things. A new habit: the medicine cabinet got a child‑proof lock and an adult‑proof system—doses logged, times noted, initials next to entries. (I initialed, because accountability is another word for love you can prove.) The kitchen counter got ruthless—no unlabeled bottles, no jars without contents and dates, no mystery drops in droppers. We used a Sharpie like it could ward off fog.

Once, as I capped the Tylenol after a teething flare—100.4° F, cranky, gums like little moons—I caught myself whispering thank you to the label for existing. This is how the heart heals after a scare: it makes gratitude for ordinary objects into a daily practice. I thanked the chart on the fridge (weight versus milliliters), the measuring syringe, the timer on my phone. I thanked the nurse whose voice came to me sometimes when I closed my eyes: by weight, not by hope.

At night, after both girls were down, I learned to sit with the jangle in my nerves without feeding it. I didn’t scroll symptoms or arguments. I didn’t draft unsent speeches to a future holiday table. I boiled water for tea I would likely forget to drink, put my elbows on the counter, and listened to the house breathe. The refrigerator hummed its square hum. The air vents sighed. Somewhere outside, a car door clicked. The ordinary orchestra of a safe home.

When the CPS worker returned with a clipboard and a tone that said careful but not suspicious, we walked the same tour as before. “Medicine cabinet?” she asked. I showed it to her: organized, labeled, dull as a filing cabinet. “Sleeping arrangements?” She peeked at the crib, approved the firm mattress. “Who has keys?” The answer had changed since her last visit. Fewer hands. Fewer surprises.

“Lily,” she said before leaving, “those photos you took helped your sister. Sometimes telling the truth feels like you’re making trouble. Often you’re making safety.”

Lily ducked her head, both shy and proud, and after the door closed she slid her tablet across the table to me. “I emptied the trash too,” she said. “So I won’t see them by accident.”

“You are allowed to take care of your own head,” I said. “That’s also safety.”

People talk about “mom gut” like it’s a superstition. I think it’s a muscle memory of every choice you’ve made that kept your child whole. The night the fever screamed at us, my gut didn’t give me medical school. It gave me verbs: call, measure, hold, say no. It gave me an index of things I knew to be true even when someone I loved told me I was being dramatic. It gave me the spine to hold the line gently and without apology.

When Ethan asked, not unkindly, if we could “let it blow over,” I knew he was asking for a kind of peace that would move the explosion from the present to the future. It’s tempting. The present is loud. Future hazards whisper, and you can tuck a whisper in your pocket and call it nothing. But safety doesn’t bargain with whispers. It tells them to get in line or get out.

On a Tuesday, Barbara sent a message through Ethan: a paragraph about intentions, about herbs her own mother had used, about how the world had gone weak and overly cautious. “Children are resilient,” she wrote, as if resilience were a substitute for good choices rather than a miracle that sometimes cleans up after our bad ones. I didn’t reply directly. I forwarded the message to my attorney, noted it in the folder, and spent my reply on Hannah’s belly, which responds to raspberries with a laugh that could rebuild a city.

A week later, Lily came home with a worksheet from school about community helpers—nurses, firefighters, social workers. She drew four boxes and filled them in with color pencils that had their own stubborn smell. Under nurse she wrote DR. PATEL, which made me smile for the way kids mash categories into the shapes that make sense to them. Under firefighter, she drew a woman with a ponytail and labeled her ABBY. Under social worker she wrote MS. KIM in careful capitals. In the last box, titled “helper in your own life,” she drew me, holding a phone in one hand and a baby in the other, a little speech bubble that said “hello 911.”

I taped the page to the fridge. Not to enshrine my face, but to enshrine the idea that asking for help is an action verb and an act of leadership. When Lily looked at that page before bed, she didn’t see a mother terrified. She saw a mother decisive. I want that to be the photograph in her mind.

We went once to the park and Lily asked to push Hannah’s stroller over the little bridge where the creek says hello to the culvert. The sun put coins on the water and threw back the trees in scattered pieces. “Do you think Grandma will come back when the paper says she can?” Lily asked, as if the question were a dragon she was brave enough to name.

“She might,” I said. “What will we do then?”

“She rings the doorbell,” Lily said, folding the rules into the world as if they’d been there all along. “We see if she remembers the rules too.”

“Yes,” I said. “We see if she remembers the rules.”

On Saturday mornings, we volunteered like we’d promised ourselves we would—the gym that smelled like bleach and donuts, the assembly lines of boxes and cans. Susan—four kids’ worth of humor—taught Lily the art of taping a box so it doesn’t open in the middle. Hannah watched from the carrier with the solemnity of a tiny auditor. Boundaries made this possible too. When you are not performing triage on your own home every hour, you can feed other people’s kitchens.

I kept a list of sentences that had saved me when my brain tried to run back into the burning building of old dynamics. I wrote them on index cards like a practical liturgy and stuck them to the inside of the pantry door:

— No honey under one. Not a myth. A rule.

— No aspirin or salicylates for infants. Willow bark counts.

— By weight, not by hope.

— 911 if the number climbs or the baby fades.

— Boundaries are care.

— Safety first, then the rest.

Sometimes I would open the pantry to grab the peanut butter and read the list without meaning to, the way a person hums a chorus under their breath. The cards reminded me that love is not the opposite of firmness. Love is the spine of it.

Spring brought court dates and papers—nothing dramatic, just the slow choreography of institutions doing what they do. The phrase temporary no‑contact moved from a thing I signed to a thing I lived without thinking, the way you live without thinking that you lock your door at night. The ruling with the review in a year arrived with the mail. I opened it over the sink. The sink kept our lives tidy: rinse, read, breathe. I did not text anyone a victory lap. It wasn’t that kind of win. It was the kind where you whisper thank you to a system you do not trust in every instance but needed in this one.

At the pediatrician follow‑up, the nurse did that little pat on Hannah’s calf that smiles without being a smile. “Looks good,” she said after the numbers were numbers again. “Keep doing what you’re doing.” That advice sounds lazy until you earn it.

Ethan and I developed a ritual for handoffs that made us feel competent: texts the night before confirming pick‑up time, the little bag of comfort items switched back and forth, the note on nap length and last bottle time so no one had to triangulate a meltdown. Rituals are boundaries that remember themselves so you don’t have to use willpower every time.

On a quiet Thursday, Lily asked if she could make a sign for our front door. “What will it say?” I asked.

“Please ring,” she said, “and also be kind.” She made letters with a black marker and decorated the border with lightning bolts and doorbells, the symbology of our recent history rendered in Crayola. She stuck it to the glass with tape and stood back like an artist.

“It tells people who we are before they come in,” she said.

It did. It told people we were a house that believed in knock first, ask first, and that kindness is not a permission slip to do whatever you want.

When December rolled back around, we did what we’d promised: small tree, paper stars, lightning bolt on top. Hannah tried to eat the paper star three times and I took it from her mouth three times, laughing. Lily taped her Character Award on the fridge again as if she could win it twice by proximity. Ethan came for his hour, put his hands in his pockets like he wasn’t sure whether he was welcome and then remembered he was—under the rules. He watched Hannah toddle between the coffee table and my knees, arm extended like she was conducting an orchestra only she could hear.

After both girls were down, I stood in the doorway of their room and let the plain miracle of sleeping children reset the clocks in my body. The night the fever hit rewired me in ways big and small; some days I could feel the solder joints and other days I just moved through rooms that were in better order than before. I tried to name what had happened without giving it more power than it deserved. We hadn’t conquered an enemy. We had chosen a template and refused to deviate.

If Barbara learns the rules, there is a doorbell. That line wasn’t a threat or a dare. It was a map. “By invitation only” hung on our fridge because Lily drew it, but also because the phrase belongs in any place where children sleep. You can love someone and still tell them the way in. You can love someone and still tell them they cannot come today.

On nights when the house is too quiet and my mind wants to write speculative scripts, I practice a different story. In it, we are older. Lily and Hannah are in shoes that leave scuffs by the door. They laugh in the kitchen. Someone knocks and we go together to answer. On the other side is anyone—maybe Barbara softened, maybe not. The door has a bell, and the bell has a sound, and the sound buys us a second to decide. That second is what we fought for without knowing its name.

The last thing I wrote in my notes app on the night everything could have gone sideways was a line of four words: “We have a plan.” It looks simple sitting there next to grocery lists and funny quotes from Lily. It is simple. It is also everything. It says: when someone tells you you’re panicking because you will not outsource your child’s body to nostalgia, trust the plan. When someone laughs and tells you it’s just teething when the number says otherwise, trust the plan. When a number turns red and your hands shake and the past offers you a tea with a story attached, trust the plan. When your daughter says, “I know who did this,” believe that telling the truth isn’t betrayal. It’s maintenance.

On Hannah’s first birthday, a quiet, cake‑smeared afternoon, I held her on my hip while Lily stood on the chair to reach the candles with a lighter I didn’t let her operate without my hand over hers. We didn’t make speeches. We didn’t post. I pressed my nose into Hannah’s hair and took a long breath of warm sugar and shampoo. Lily looked at me over the little fire and smiled with her whole face, the kind of smile you can only make when you know you live in a house with a plan and a door that works.

Later, after the girls were wrestled into pajamas and the floor had been mopped of frosting and small, sticky footprints, I opened the pantry to put away the flour and saw the index cards again. I read them without meaning to, hummed their tune under my breath, and slid the door shut. Boundaries aren’t noisy. They are the quiet grooves a family’s wheels run in when the road is steady. We are not perfect drivers. But we stay in our lane.

If you ask me what I remember most about the worst hour of that night, it isn’t the siren or the beep or even the number. It’s Hannah’s hand, damp and heavy on my collarbone, a weight that said I am here and you are here and we are not done. It’s Lily’s whisper, “I know who did this,” which, translated into adult, means, I can carry a corner of this truth; you don’t have to lift the whole thing alone. It’s my own voice, smaller than I wanted and stronger than I expected, saying, “Acetaminophen,” and then, later, “911,” and then, later still, “No.”

Families are made of these. Not holiday photos. Not matching outfits. Not recipes that claim the authority of time. Families are made of a thousand tiny, unglamorous no’s in service of a few luminous yeses. Yes to safety. Yes to sleep. Yes to trust. Yes to a door that rings and a plan that holds. Yes to numbers that tell the truth and to hands that do the next right thing without applause.

When I tuck the girls in now, I don’t tell them they’re brave. I tell them they’re loved and safe. Brave is a word the world can’t wait to spend. Safe is the account I guard with my life. On some nights, Hannah’s forehead is warm again—100.4° F, two teeth like pearls pushing at her gums. We do the math by weight, not by hope. We turn on a cartoon and let the colors sing at a volume the neighbors can’t hear. Lily brings the throw blanket like a liturgy. We practice, and then we practice again.

If you come to our door, you will see a sign in marker and construction paper that says ring and be kind. You will see a lightning bolt on a fridge held up by magnets shaped like fruit. You may not see the index cards because they are tucked away where I can read them when my hands tremble. You will not see, but you will feel, the way the house itself has learned to be a good steward of its people—how the air moves, how the evening lands. You will understand, even if you can’t name it, that safety has a smell (vanilla and cinnamon), a sound (laughing and a refrigerator hum), a color (paper stars and soft lamp light). You will understand that the plan is not a poster on the wall; it is the way we move.

And if, one day, the bell rings and it is someone we have loved in ways that hurt, we will do what we do. We will look at the sign. We will listen to the bell. We will count to the number that calms our hands. We will open or we will not. We will keep the children safe. We will be the grown‑ups we promised to be on a night when the numbers turned red and we said no, and the world, to our astonishment, said, Good. Keep going.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load