My parents skipped my wedding because their dog was sick, and now I sit at my little kitchen table in our starter house in Ohio, staring at my phone while an invitation to Thanksgiving glows on the screen. Next to it, a glass of iced tea sweats onto a coaster printed with a faded American flag, and the fridge hums behind me, a flag magnet pinning up a picture of my parents’ Labradoodle, Muffin, in a ridiculous sweater.

I screenshot Muffin’s latest Instagram post—a close-up of her in a tiny party hat surrounded by dog-safe cupcakes—and attach it to my reply. My thumbs hover for a second before I type the same sentence they once gave me.

“Sorry, we can’t make it. Tom hasn’t been feeling well. I need to stay home and take care of him.”

Before I hit send, I think about the twelve missed calls from my mom on the morning of my wedding and the two empty chairs at the front of the chapel. If Muffin could be their child, then my husband was going to be mine.

My parents got Muffin three years before my wedding, and from day one, that dog became the center of their universe. They bought her a custom velvet dog bed that cost more than my first used Honda. They hired a professional photographer to take weekly pictures for her Instagram account. They canceled plans with me if Muffin seemed tired, or moody, or “just a little off.”

When I called to say I’d been promoted and wanted to take them to dinner downtown to celebrate, Mom said, “Oh honey, we’d love to, but Muffin had an upset stomach this morning. We should stay close in case she needs us.”

They missed that dinner.

When I walked across the stage to get my college diploma, the seats I’d saved for them stayed empty. Later, Mom texted a photo of Muffin lying sadly on her velvet bed and wrote, “She was vomiting all night. We couldn’t leave her. We’re so proud of you though!”

They missed my graduation.

My birthday cookout? They left halfway through because Muffin looked “a little sad” on the pet camera. They waved at me with apologetic smiles, juggling a to-go container of ribs while my friends watched them hustle out the door.

By then, the pattern was obvious, but I kept telling myself it would be different when something truly important happened. Something like my wedding.

I’d been with Tom for five years when he proposed on a quiet Sunday evening, in our living room, Sinatra playing faintly from a Bluetooth speaker. I called my parents that night, my hands still shaking, and Mom screamed into the phone.

“Finally! Oh my gosh, tell me everything. When? Where? What are you thinking for colors?”

They spent five minutes congratulating me, then thirty straight minutes telling me about the new trick Muffin had learned: ringing a tiny bell on the back door when she wanted to go outside.

I laughed it off. I shouldn’t have.

Over the next fourteen months, they were deeply involved in wedding planning. Mom came with me to dress shops, crying when I stepped out of the fitting room in a lace gown, whispering that she’d dreamed of this moment since the day I was born. Dad practiced our father–daughter dance in their living room, his hands a little stiff, while Muffin watched from her velvet bed like a furry chaperone.

They helped pick the venue, taste the cake, and even weighed in on whether peacock blue would clash with my bridesmaids’ dresses. Dad emailed me a draft of his speech and texted, “Is five minutes too long?”

“Not if you can get through it without crying,” I wrote back.

He sent a laughing emoji and said he’d try.

They invited forty of their friends and insisted on paying for the open bar so everyone could “really celebrate.” A week before the wedding, Mom called to confirm what time they needed to be there for photos. She sounded giddy.

“Oh, I can’t wait to see you in your dress again. I found the perfect peacock-blue gown. It’ll pop so nicely in the pictures.”

Dad texted the next morning: “We’re so proud of you, kiddo. See you at the rehearsal dinner.”

Everything felt perfect.

The morning of my wedding, I woke up in the bridal suite of the little chapel hotel we’d rented, sunlight spilling across the bed, my dress hanging from the curtain rod. My phone showed twelve missed calls from Mom.

My heart dropped. Twelve missed calls didn’t feel like “We’re running late.” Twelve missed calls felt like death, or a car crash, or something that would split my life into before and after.

I called her back with shaking hands. She was sobbing so hard I could barely understand anything. Dad took the phone.

“Hey, kiddo,” he said, his voice tight. “We’re at the emergency vet. Muffin threw up last night and now she won’t eat breakfast. She seems kind of lethargic.”

I swallowed. “Is she dying?”

“No, no,” he rushed to say. “The vet thinks she probably just ate something weird on her walk yesterday. They’re running fluids and monitoring her. But your mom is really shaken up.”

Relief and anger collided in my chest.

“Okay,” I said slowly. “So when you’re done at the vet, you can head straight to the venue. We still have three hours before the ceremony. You’ll make it in time.”

Mom took the phone back, her voice high and thin.

“We can’t leave her when she’s like this,” she said. “She needs us. We’ll try to make the reception if she perks up, but we just can’t leave her alone while she’s not eating.”

I stared at my reflection in the hotel mirror, hair half done, the curling iron cooling on the counter.

“My wedding is today,” I said. “I’m getting married in three hours.”

“I know, sweetheart,” Mom said quickly. “We’ll celebrate later, I promise. But Muffin is our baby. She needs us right now.”

That was the sentence that turned something in me to stone.

My makeup artist stepped into the room and paused when she saw my face. “Everything okay?” she asked gently.

I opened my mouth, but tears came out first. I could barely choke out, “My parents aren’t coming.”

Tom’s mom offered to walk me down the aisle. Tom’s dad stood tall and quiet and serious, the way my father should have. My bridesmaids kept glancing at the doors like my parents might burst through at any second, breathless and apologetic.

They didn’t.

The two chairs in the front row that said RESERVED FOR PARENTS stayed empty. I could feel my aunt Katie’s rage burning from across the aisle as she fired off text after text to my mom, each one angrier than the last. My parents’ forty friends whispered among themselves, confused and embarrassed.

During the father–daughter dance, the DJ called my dad’s name, then hesitated. Tom stepped in and pulled me close, we swayed to a song I’d picked for another man. The photographer kept asking when we could grab my parents for family photos, and I had to keep saying, “They’re not coming.”

By the time we cut the cake, I’d stopped checking my phone. Eventually, a text came through with a picture of Muffin lying on a blanket at the vet, a little bandage on her paw.

“She’s feeling better,” Mom wrote. “We’ll celebrate with you later. Love you!”

There was no apology. Just a dog and a promise that “later” never kept.

When I told them how hurt I was, Mom called Muffin’s episode “a medical emergency” and said I was being insensitive to their “other child.” Dad added that he thought I’d understand putting your child’s needs first.

Muffin was their child.

I was their only actual daughter, and they chose the dog.

That was the night my revenge policy was born.

Three days after that conversation, my phone buzzed while I was scrolling through pictures from the wedding we’d had without them. My parents’ text lit up the screen.

We’re having dinner for Mom’s birthday at that Italian place downtown Thursday at 7. Can you and Tom make it?

I stared at the message for twenty minutes, the taste of our dry wedding cake still strangely vivid in my mouth. Tom sat next to me on the couch, flipping channels.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

I showed him the text.

My thumb hovered over the keyboard. Finally, I typed, Tom hasn’t been feeling great lately. I should stay home and make sure he’s okay. We’ll celebrate another time when he’s feeling better.

I hit send before I could talk myself out of it.

Mom called within a minute.

“What’s wrong with Tom?” she asked, her voice sharp with worry. “Is it serious? Do you need us to bring soup? We can swing by Target and grab Gatorade.”

I kept my voice light. “It’s nothing major. He’s just really tired and needs to rest. We’ll do something for your birthday when he’s up for it.”

She asked if he’d been to the doctor. I said we were watching it. I ended the call after a few minutes with a vague promise to update her.

This time, the empty chairs were at their dinner table, not mine.

A week later, Dad texted to ask if we wanted to come over for Sunday pot roast like we used to once a month.

Can’t, I wrote two hours later. Tom’s having one of those days where he just needs quiet. Maybe next month.

Dad called ten minutes later.

“We can eat earlier if that helps,” he offered. “Or just grab coffee somewhere close to you. We haven’t seen you since the wedding.”

I stared out the kitchen window at the neighbor’s flag waving on his porch.

“He really just needs to take it easy,” I said. “I don’t want to push him.”

Dad sighed. “Okay. We’ll try again next month. Tell him we’re thinking about him.”

Two weeks after that, Mom invited us to a backyard barbecue for some of Dad’s coworkers. I texted back that Tom had been dealing with some stomach issues and didn’t feel up to being social.

“Is he okay?” she replied immediately. “Has he tried cutting dairy? Maybe it’s stress. He should see a doctor. I know a good gastro in town.”

I thanked her for the suggestions, kept my tone friendly but not warm—the same way she’d sounded explaining why their dog’s upset stomach outweighed my wedding.

That night, Tom came home to find me on the couch, phone in hand.

“You look like you’re trying to defuse a bomb,” he said, setting his briefcase down.

I told him everything—Mom’s birthday, Sunday dinner, the barbecue, all the “Tom’s not feeling great” excuses.

He sat beside me, quiet for a long moment.

“I support you,” he said finally. “But I also want to make sure you’re okay. Is this helping?”

“It feels fair,” I said. “They chose Muffin over me for three years. They missed my wedding for a dog with a mild stomach bug. All I’m doing is giving them the same ridiculous reasons back.”

He nodded slowly. “Just…promise you’ll tell me if it starts hurting you more than it hurts them.”

The first real crack in my policy showed up at my aunt Katie’s anniversary party. She and my uncle had been married thirty years and were throwing a big backyard celebration. When she called to invite me, I said, “Of course. We’ll be there. What can I bring?”

She mentioned that my parents had acted weird when she’d asked if I was coming.

“They changed the subject so fast I got whiplash,” she said. “Is everything okay?”

“It’s complicated,” I told her. “But I’ll be there.”

Tom and I got to Katie’s early to help hang string lights and set out folding chairs. My parents arrived half an hour later. I watched Mom’s face when she spotted us across the yard. Her eyes went wide, and she grabbed Dad’s arm.

They walked straight over.

“I thought Tom wasn’t feeling up to things,” Mom said, her voice tight.

“He’s having a good day,” I answered, giving her the same sweet smile she’d used on me. “We wanted to take advantage of it while we could.”

Dad pulled Tom aside later, near the fence, gesturing with his hands, his brows drawn together. I pretended to be engrossed in a conversation with my cousin but kept watching them out of the corner of my eye.

When we got home, Tom said, “Your dad asked if I’ve been sick.”

“What’d you say?”

“I told him I’ve been fine. Maybe there was some confusion.”

My dad’s text arrived the next morning.

Have you been lying about Tom being sick this whole time?

The words vibrated on the screen.

When Mom called an hour later, she didn’t say hello.

“Have you been making all of this up?” she demanded. “All these dinners and barbecues you’re skipping—have you been lying to us, using Tom’s health as an excuse?”

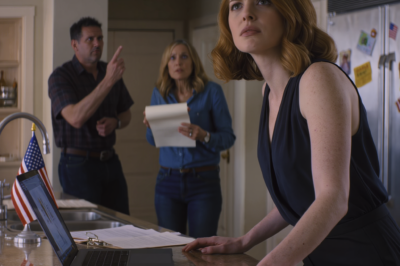

I leaned against the kitchen counter, staring at the flag magnet on my fridge holding up Muffin’s party-hat photo.

“I’ve been doing exactly what you did,” I said calmly. “Putting someone I love first. Using the same vague health excuses you used for Muffin. You missed my graduation. My promotion dinner. You left my birthday early. You missed my wedding because she had an upset stomach. All I did was mirror your pattern for three months.”

Mom went silent so long I had to check the call hadn’t dropped.

“That’s completely different,” she said finally. “Muffin was actually sick.”

“She threw up once,” I replied, my voice shaking now. “The vet said she probably ate something weird on a walk. You admitted she wasn’t dying. But you stayed at the vet instead of coming to my wedding. Tell me how that’s different.”

“You’re twisting everything,” she snapped. Then she hung up.

The click of the call ending felt like a door slamming shut.

In the following weeks, my phone filled up with evidence that my revenge was working and also failing at the same time. Word started spreading through the family. Uncle Donald cornered Tom at a work function, asking bluntly why my parents weren’t at our wedding. Tom told him the truth: Muffin was sick, and they stayed at the emergency vet instead.

Katie called me from the cereal aisle at Target, whispering like we were plotting a heist.

“Half the family is talking about it,” she said. “Your parents missing your wedding for the dog. And now you skipping their events because ‘Tom’s tired.’ Honestly? I kind of admire the symmetry.”

Her approval felt like a shot of espresso straight into my veins.

But Michaela’s visit, a few days after Christmas, felt like cold water.

She showed up at our apartment with a Tupperware of cookies and a worried look.

“How were the holidays?” she asked.

I told her the short version: the invitation from my parents, my refusal, the quiet Christmas with just me and Tom opening presents under our small fake tree while a rerun of the Macy’s parade murmured in the background.

“You’ve been talking about this nonstop for months,” she said gently. “Every time we get coffee, it circles back to what excuse you used or how your parents reacted. Are you…sure this is helping you?”

“They hurt me, Michaela,” I said, my voice sharper than I meant. “They missed my wedding.”

“I know,” she said. “And that’s huge. I’m not downplaying it. I just—I’m watching you build your whole emotional life around making them feel what you felt. That’s not the same as healing.”

I stood up and went to the kitchen, pretending to refill my water. “I appreciate your concern,” I said stiffly. “But I’m handling it.”

“That’s what worries me,” she said quietly. “That this is you handling it.”

After she left, I slid down the kitchen cabinet and sat on the floor. For the first time, my carefully stacked anger started to wobble.

Tom found me there and joined me on the tiles.

“I don’t want this to eat you alive,” he said.

That was the night he suggested therapy.

I found Beth online, scrolling through profiles on my insurance website. Her bio said she specialized in family conflict and adult children navigating complicated relationships with parents. Her office was in a low brick building with a tiny American flag stuck in a flowerpot by the door.

The waiting room smelled like coffee and lemon cleaner. Boring landscapes hung on the walls. Beth herself looked like every comforting teacher I’d ever had—gray hair, glasses, soft sweater, box of tissues within arm’s reach.

“So,” she said after I sat down. “Tell me what brings you here.”

I started with the wedding, then rewound three years to Muffin’s arrival: the custom bed, the Instagram, the canceled plans. I told her about the twelve missed calls, the empty chairs, the photo of Muffin at the vet in place of my parents’ faces in my wedding album.

Then I explained my policy: giving my parents the exact same ridiculous excuses they’d given me. Tom’s fatigue. Tom’s stomach. Tom’s anxiety about crowds.

Beth listened without interrupting.

“And what are you hoping this policy will accomplish?” she asked when I finished.

“I want them to understand,” I said. “I want them to feel what it’s like when someone you love keeps choosing something else over you.”

“Do they seem to understand?” she asked.

I thought about the angry texts, the accusations that I was manipulative.

“Not really,” I admitted. “They think I’m being cruel to them and unfair to Muffin.”

“And what do you want besides understanding?” she asked. “Do you want a relationship with them? An apology? Changed behavior? Or do you mostly want them to hurt the way you hurt?”

The questions landed like stones.

“I don’t know,” I said finally.

Beth nodded. “Then that’s where we start. Because if you don’t know what you want, it’s hard to tell if what you’re doing is getting you there.”

The next few weeks were a blur of therapy sessions and family drama. My parents sent a long email accusing me of “turning the family against them” and “making them look like bad parents instead of responsible pet owners.” I left it unread for three days, then replied with one sentence:

I’m sure you’ll understand if I prioritize my husband’s needs over family events, just like you taught me.

When they invited us to Christmas Eve dinner, I replied that we were planning a quiet holiday at home because big gatherings made Tom anxious nowadays. Mom responded with a string of question marks and called to demand why I was “doing this.”

“I learned from the best,” I said before hanging up.

But every time I fired off a clever line, the satisfaction felt thinner.

One evening in early spring, after a flurry of furious texts from my parents about how I was “weaponizing” Tom, I blocked their numbers. I told myself it was for my peace of mind, but the silence felt heavy and strange.

On day six of radio silence, my uncle Gregory called.

“Kiddo,” he said, “this is getting bad. Your mom cried at Sunday dinner. Your dad yelled at the TV for an hour. I’m not saying you’re wrong, but…can I help mediate? Would you even be open to that?”

“I’ll think about it,” I told him. And I meant it.

Two days later, I unblocked my parents’ numbers. My phone buzzed immediately with a backlog of missed calls, voicemails, and texts. Most of the messages were defensive or angry.

But one voicemail from Mom sounded different.

Her voice was rough, like she’d been crying.

“We’ve been at the vet a lot lately,” she said. “Muffin’s getting older. Arthritis, heart issues. We’re suddenly realizing how much time we’ve spent here. How much we missed with you because we were sitting in waiting rooms like this.”

She inhaled shakily.

“I am so sorry,” she said. “Not ‘sorry you’re upset.’ I’m sorry for what we did. For the times we chose our dog over our daughter. I don’t know how to fix it, but I know it was wrong.”

I played that voicemail three times.

I still didn’t call her back.

A week later, my aunt Ila called, her voice brisk and warm all at once.

“I finally got the full story,” she said. “I confronted your parents at dinner. I asked them straight out why they weren’t at your wedding.”

“What did they say?”

“A lot of nonsense at first,” she replied. “About Muffin being sick and you overreacting. I didn’t let them off the hook. I told them choices have consequences, and they don’t get to be shocked that you set boundaries after three years of being second place.”

I swallowed hard.

“Do you think they heard you?”

“I think,” she said slowly, “that they started to. People don’t change overnight. But you shook something loose.”

A few days after that, Dad texted, asking if I’d meet him for coffee. “No big confrontation,” he wrote. “Just a conversation. Your call.”

I took the question to Beth.

“Do you feel emotionally safe enough to hear him out?” she asked.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever feel ready,” I said. “But I’m tired of feeling stuck.”

She smiled gently. “Sometimes moving forward feels like standing on a trapdoor. It doesn’t mean it’s the wrong door.”

We met at a coffee shop halfway between our houses, the kind of place with Edison bulbs and chalkboard menus. Dad was already there when I walked in, sitting at a corner table with two cups of coffee. He’d ordered my usual, which somehow made my throat tighten.

“Hey, kiddo,” he said, standing up awkwardly before sitting back down.

For a minute, we just sat there, steam curling between us.

“I got so wrapped up in that dog,” he said finally. “We both did. It started as something small—she needed us, she was cute, she was an easy thing to focus on when life felt…hard. And then suddenly we were pouring everything into her and not noticing what we were taking away from you.”

He looked up, eyes damp.

“Missing your wedding,” he said, “is the biggest regret of my life. Not one of. The biggest.”

My heart pounded.

“It wasn’t just the wedding,” I said. “That’s what you have to understand. It was three years of being rescheduled and canceled and cut short. My graduation. My promotion. My birthday. Standing there in my dress with twelve missed calls from Mom on my phone and realizing you were choosing the vet over the chapel…that was just the proof I couldn’t ignore anymore.”

He nodded, tears streaking down his face.

“I know ‘sorry’ isn’t enough,” he said. “I know that. But I am sorry. And I’m ashamed it took you mirroring our behavior for me to see how bad it was.”

For the first time, I believed he understood at least part of it.

In my next session, Beth asked if I was tired of my revenge policy.

“Yes,” I said, the word tumbling out before I could soften it. “I’m exhausted. Keeping track of excuses, blocking and unblocking numbers, replaying everything in my head. It’s like carrying weights I refuse to set down.”

She nodded. “Then maybe it’s time to separate two things: punishment and protection. You can stop punishing them without dropping your boundaries.”

It sounded simple. It felt enormous.

That night, I typed a text to my parents.

If we talk, I need you to actually listen this time. No defensiveness, no excuses. Just listening to how your choices affected me. If you can do that, I’m willing to try.

Mom replied within a minute.

We’ll do whatever it takes.

Gregory offered his house as neutral ground. Walking up his front steps felt like walking into an exam I hadn’t studied for.

My parents sat together on his couch, their hands folded, looking smaller than I remembered. Tom sat next to me on the opposite couch, Gregory in an armchair like a referee who hadn’t decided which whistle to use.

I started talking before I could lose my nerve.

I told them about every missed event, every last-minute cancellation. The way my stomach dropped each time they chose Muffin over me. How the dog bed got more attention than my big moments. How sitting in a bridal suite with my phone showing twelve missed calls and zero parents changed something in me.

Mom cried through most of it. Dad kept saying “I’m sorry” until I finally held up a hand.

“I need you to understand before you apologize,” I said. “Otherwise the apology doesn’t land anywhere.”

When I finally ran out of words, Mom took a shaky breath.

“After you were born,” she said, “we tried for years to have another baby. It never happened. We never really dealt with that. When we got Muffin, all that leftover…parent energy had to go somewhere. We poured it into her. It sounds ridiculous, I know. But it felt like we finally had something that needed us again.”

She shook her head, tears dripping onto her jeans.

“And we let that replace you,” she said quietly. “We let our dog become our focus instead of our actual daughter.”

Dad nodded. “We forgot that you still needed us—just in different ways.”

I took a deep breath.

“My revenge policy was wrong,” I said. “I know that. But it came from a place where I felt like your second choice for years. I needed you to feel what it was like being canceled on, being told someone else’s needs came first.”

Dad looked at me, eyes red.

“I get it now,” he said. “I wish to God it hadn’t taken this to wake us up, but I get it.”

We talked for three hours. Gregory mostly sat quietly, stepping in only when things veered too far toward defensiveness. By the end, my parents promised concrete changes: dog sitters for events, no more last-minute bailouts for non-emergencies, a commitment to show up and stay present.

“I’m not going to trust words right away,” I told them. “I need to see consistency over time.”

“That’s fair,” Dad said.

The next few months felt like walking on a new floor I didn’t quite trust. They invited us to dinner at their house.

We showed up at six. The table was set, food ready, no frantic texts about Muffin’s mood or appetite. They didn’t mention their dog once until Tom asked how she was.

“She’s good,” Mom said simply. “We hired a sitter for the night so we could be here.”

The words landed like a quiet miracle.

At Caleb’s backyard cookout later that summer, they arrived on time, stayed the whole afternoon, and helped clean up folding chairs as the sun went down. At Katie’s birthday dinner, they didn’t leave early. They brought a homemade cake instead of photos of Muffin.

At Michaela’s baby shower, they showed up with a thoughtful gift and stayed to help stack gift bags in the corner.

I noticed every small choice.

Beth called it “data.”

“Each time they show up and stay, that’s one more data point,” she said. “You’re allowed to be cautiously hopeful while still grieving what you lost.”

Priscilla got engaged in the middle of all this. When she called, breathless and squealing, asking if I’d be a bridesmaid, I said yes immediately. Then her voice grew tentative.

“Is it going to be weird with your parents?” she asked. “I mean…after everything?”

I thought about their recent streak. “I think they’ll show up,” I said. “They’ve been trying.”

In the months leading up to her wedding, my parents texted me twice to confirm the date and time. It annoyed me that I didn’t fully trust them, even when they were doing exactly what reliable people do: double-checking details.

The morning of Priscilla’s wedding, my phone pinged with a text from Mom.

Leaving now. We’ll be there by 3:00.

When the bridal party pulled up to the church at 2:30, my parents’ sedan was already in the parking lot. They stood near the entrance, dressed and ready. Dad gave me a thumbs-up as we walked in.

During the ceremony, they sat in the third row on the bride’s side and stayed glued to their seats, eyes on the altar. At the reception, Dad gave a toast about family and the importance of showing up.

“We don’t always get it right,” he said, voice cracking. “But we can learn, and we can do better.”

My eyes filled. I didn’t know if I was crying for the speech he was giving now or the one he never gave at my wedding.

That night, after Tom and I got home, I pulled our own wedding album out of the closet for the first time in months. I flipped to the page with the ceremony, staring at the two empty chairs in the front row.

The hurt was still there, but it felt different—less like an open wound and more like a scar that ached when the weather changed.

Around Thanksgiving, Katie hosted the family at her place. Her dining room table was extended with every leaf, mismatched chairs squeezed in around it. Tom and I brought mashed potatoes and his famous green bean casserole.

My parents arrived right on time with a pumpkin pie. Someone asked how Muffin was doing.

“She’s slowing down,” Mom said. “We hired a sitter so she’d be comfortable at home today.”

Then she changed the subject to Caleb’s new job. I watched the shift in real time. The conversation moved away from their dog and toward the people sitting around the table.

Later, loading dessert plates into the dishwasher, Dad bumped my shoulder lightly.

“I’m grateful we’re all here,” he said.

“Me too,” I answered. And I meant it.

Beth asked in our next session if I was ready to forgive them.

“I don’t know if ‘ready’ is the right word,” I said. “Some days, yes. Other days, I see those empty chairs in my mind and it’s like I’m back in that chapel.”

“Forgiveness doesn’t have to be all or nothing,” she said. “You can move forward with them, acknowledge their effort, and still carry some hurt. Both can be true.”

That Christmas, my parents invited us over for a small, quiet holiday. Just the four of us. The house smelled like ham and cinnamon. We exchanged gifts in the living room—Tom got a watch, I got a gift card to my favorite bookstore.

When we were putting on our coats to leave, Mom handed me one more box.

“I made something for you,” she said. “I hope it’s okay.”

Inside was a photo album with OUR DAUGHTER’S WEDDING written in silver letters on the cover. My hands shook as I opened it.

Every professional photo from my wedding was there. The ceremony. The reception. The cake cutting. Me with my bridesmaids. Tom with his groomsmen. No parents, because they hadn’t been there—but the moments were preserved.

On the inside cover, in Mom’s neat handwriting, was an inscription.

I can’t be in these pictures, but I want to honor the day I should have been there for. I am so sorry I wasn’t. I love you more than I can ever say, and I hope someday you can forgive me.

Tears blurred the words. Mom stepped forward and hugged me. This time, I let her.

Driving home, the album rested on my lap. When we walked into our kitchen, I set it on the table next to my glass of iced tea and glanced at our fridge.

The flag magnet was still there, but it no longer held a photo of Muffin in a party hat. Instead, it held a picture from Priscilla’s wedding—me, Tom, my parents, and my sister, all standing together, all actually present.

In February, Tom and I started house hunting. After years of renting, we finally had enough saved for a down payment. We found a three-bedroom place with a small yard and a porch big enough for two rocking chairs. The offer was accepted on a Tuesday.

When I called my parents with the news, they sounded genuinely thrilled. Two days later, Mom called back.

“We’d like to help with the down payment,” she said. “We know it doesn’t fix anything, but we want to contribute to your future.”

I took the idea to Beth.

“I don’t want to feel like I ‘owe’ them,” I said. “Or have them use it as leverage.”

“You can accept a gift and still have boundaries,” Beth said. “Tell them your conditions. If they can’t respect that, you can say no.”

So I did. I told my parents I’d accept the money only if it was a no-strings-attached gift that would never be brought up as a bargaining chip.

“Of course,” Dad said. “No strings.”

We closed on the house in March. Their check covered half the down payment.

On moving day, they showed up at 8 a.m. sharp. Mom brought a cooler full of sandwiches and bottled water. Dad carried in cleaning supplies and found the toolbox without being asked. They spent the entire day helping us unpack, hanging pictures, organizing kitchen cabinets.

At lunch, someone asked about Muffin.

“We left her with the sitter,” Mom said. “We wanted to be here all day.”

I glanced at her, then at Dad. He didn’t look guilty, just solid and present.

They stayed until after six, long after the sun started to set and the neighbors’ porch lights flicked on one by one. As they left, Dad hugged me on the front porch, the cool air smelling faintly of someone’s barbecue down the street.

“I’m proud of you,” he said. “Of both of you.”

Six more months went by. My parents kept showing up. Dinners. Cookouts. Baby showers. They still loved their dog, but Muffin no longer sat in the center of every story.

One Saturday, Michaela and I sat on my back porch with iced tea, watching the sunlight hit our new fence. She studied me for a second.

“You seem lighter,” she said. “Like you’re not carrying a hundred pounds on your shoulders anymore.”

“I stopped waking up mad,” I admitted. “Most days, anyway.”

“You’re still allowed to be mad sometimes,” she said. “You just don’t live there anymore.”

Looking back over the last eighteen months, I could see it clearly. My revenge policy hadn’t healed me. It hadn’t made my parents magically understand or rewound time to put them in those empty chairs.

But it did force a reckoning. It held up a mirror they couldn’t ignore, even if it took therapy, hard conversations, and a lot of tears for all of us to really look.

We can’t get back the years where Muffin’s needs outranked mine, or erase the photo in my mind of two reserved chairs sitting empty while I walked down the aisle on Tom’s father’s arm. Those losses are part of my story now.

What we do have is a messy, fragile, real attempt at something new. My parents hiring dog sitters so they can show up. Me setting boundaries without turning them into weapons. A fridge where the flag magnet holds family instead of a dog in a party hat.

Some days, the hurt still catches me off guard. I’ll hear a wedding song in the grocery store or catch sight of our album on the shelf and feel that old ache.

But most days, I choose to keep moving forward—not because what they did was small, but because I am finally ready for my life to be bigger than the worst thing they ever did.

If Muffin was their child once, my husband and I are building a life now where I get to be my own priority, too.

I used to think that was the end of the story—me at our kitchen table with my iced tea sweating onto a faded flag coaster, my parents finally showing up to things, Muffin fading into the background of our lives. A neat little moral about boundaries and growth. But life never wraps itself up in one clean closing line.

A few weeks after moving day, Mom called while I was unloading a box of books in the new living room. Tom was in the garage wrestling with a stubborn shelf.

“Hey, sweetheart,” she said. “Do you have a minute?”

Something in her voice made me sit down on the edge of a still-unassembled IKEA cabinet.

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s Muffin,” she said. “The vet found something on her last checkup. Her heart’s getting weaker. They think we might have…a year? Maybe less.”

The words floated between us. For three years, that dog had been the center of every canceled plan, the star of an Instagram account, the reason my parents skipped my wedding. I’d spent the last eighteen months deliberately de-centering her in my mind. Hearing that she was actually, genuinely sick knocked the wind out of me in a way I didn’t expect.

“I’m sorry,” I said, and realized I meant it.

Mom sniffed. “We’re trying some meds, changing her diet. The vet says we’ll know more in a couple of months. I just…wanted you to know. And I wanted you to hear it from me, not through the family group chat.”

“Thank you for telling me,” I said.

After we hung up, I sat there staring at the half-empty box of books. Tom came in, wiping dust off his hands.

“You okay?” he asked.

“They think Muffin has a year,” I said. “Maybe less.”

He sat down next to me. “How do you feel?”

“Like I should feel nothing,” I said. “But I don’t. I’m sad for them. And also…angry that this is what finally forced them to look at how they’d been living.”

He nodded. “You’re allowed to feel both.”

Therapy that week was heavier than usual. Beth listened while I explained the diagnosis.

“So now the dog that symbolized your parents’ neglect is actually dying,” she said gently. “That’s a lot to hold.”

“It feels like the universe is punishing me for every petty thought I’ve had about that dog,” I admitted. “Like I wished she’d disappear and now she might.”

Beth shook her head. “You didn’t cause this. You’re not that powerful. What you can decide now is what role you want to play as this unfolds. Not to please or punish your parents, but for your own integrity.”

I thought about that for a long time. About who I wanted to be, not just who I wanted my parents to be.

My extended family had opinions, of course. The group text my cousins kept going year-round lit up the day after Mom’s call.

I heard about Muffin 😢, Priscilla wrote. Are your parents okay?

They’re devastated, I typed. We’re…managing.

Gregory chimed in with a series of emojis—dog, broken heart, prayer hands. Donald made a joke about making sure my parents didn’t miss any important events for vet appointments that actually made me laugh, even though I immediately felt guilty for it.

Michaela texted me separately.

How are YOU? Not them, not the dog. You.

I stared at the question and then wrote back: Complicated.

She sent a heart and said, That makes sense.

My parents started structuring their lives around medication schedules and cardiology checkups. The difference now was that they told me about it ahead of time instead of using it as a last-minute excuse. Mom would text, We have a cardiology appointment for M this Thursday at 3. We’ll be a little late to Katie’s thing but we’ll still be there. And they were.

Every time, I felt the old panic rise—the waiting-for-the-cancellation feeling—only to have them walk through the door anyway, slightly frazzled but present.

One Sunday afternoon in late summer, Dad called.

“We’re at the emergency vet,” he said. “Muffin fainted in the yard.”

I was standing at our kitchen counter, slicing limes for the iced tea I made almost ritualistically now. The TV hummed soft background noise in the living room, some game Tom had on low.

“Is she…?” I couldn’t finish the sentence.

“She’s stable now,” he said quickly. “They’re keeping her overnight for observation. Your mom’s a wreck. I’m okay-ish.” He laughed once, without humor. “Hospitals and waiting rooms, right?”

The room tilted for a second. A different waiting room, a different day, twelve missed calls, a different choice.

“Do you want me to come?” I heard myself ask.

There was a beat of stunned silence.

“You’d do that?” he asked.

“I don’t know if it’s a good idea,” I said honestly. “But I can sit with Mom for a bit. If you want.”

Tom drove. The emergency vet hospital was on the other side of town, a low building with big windows and manicured shrubs out front. An American flag fluttered on a pole near the entrance, the same kind of cheap fabric that gets hung outside school gyms and post offices.

As we pulled into the lot, my chest tightened. My parents’ car sat near the entrance, hazard lights blinking like a heartbeat you can’t ignore.

Inside, the chemical-clean smell hit me first. A TV in the corner played some home renovation show on mute. A couple with a cat carrier sat holding hands. A kid in a soccer uniform sniffled quietly next to a golden retriever with a bandaged paw.

Mom sat in one of the plastic chairs, her shoulders rounded, clutching her phone in both hands. Dad stood next to her, one hand on her back.

When she saw me, her face crumpled.

“You came,” she said, standing up so fast her purse slid off the chair.

“Yeah,” I said. “I did.”

She hugged me like she was afraid I might vanish. For a second, my body stayed tense. Then something in me softened. This wasn’t my wedding day. This wasn’t a choice between me and the dog. This was just a hard thing they were going through.

“How is she?” I asked.

“Sleeping,” Mom said, wiping under her eyes. “They’ve got her hooked up to a bunch of machines. She looks so small.”

The phrase landed somewhere deep. I remembered being ten, waking up from having my tonsils taken out, my parents sitting on either side of the hospital bed, faces lined with worry. Back then, I’d been the small one.

We sat together in the waiting room. Dad filled me in on the vet’s plan, on medication adjustments, on what “quality of life” meant in this context. Tom sat quietly on my other side, a steady presence.

At one point, Mom whispered, “I keep thinking about your wedding. About how we chose this place over that chapel. If I could go back—”

“You can’t,” I said softly. “But you’re here now. And I’m here now. That has to count for something.”

She nodded, tears spilling over again.

We stayed for an hour. When the vet tech came out to give another update, Mom insisted on introducing me.

“This is our daughter,” she said. “The one I told you about.”

I didn’t know what exactly she’d told them, but the tech smiled kindly and said, “You’ve got a good support system here.”

On the drive home, I stared out the window at the darkening sky. Streetlights flicked on, cars lined up at red lights, flags drooped in front yards in the heavy summer air.

“Are you okay?” Tom asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “But I’m glad I went.”

Beth called it a “reclaiming.”

“You went to an emergency vet on your own terms,” she said at our next session. “Not because your parents were choosing it over you, but because you chose to show up for them. That’s different.”

Over the next few months, Muffin’s health became a strange background metronome in our lives. My parents would text quick updates—Good day today; she chased a squirrel. Rough night; she coughed a lot.

Sometimes Mom sent videos of Muffin shuffling across the yard in a tiny sweater to keep her warm. Once, she sent a picture of Muffin asleep with her head on Dad’s work boot.

“I know it’s silly,” Mom wrote, “but I’m grateful for every day.”

I’d expected to feel nothing but bitterness when I saw those images. Instead, I felt a complicated mix of tenderness and grief—for them, for the years we lost, for the version of our family that never got to exist.

The social ripples continued. At a Fourth of July barbecue in Caleb’s backyard, while kids ran around with sparklers and someone’s playlist rotated between Springsteen and country covers, Ila cornered me near the cooler.

“I’ve been watching your parents,” she said, popping the tab on a can of soda. “They’re different.”

“I know,” I said. “I see it too.”

“They talk about your house more than they talk about the dog now,” she said. “That’s new.”

We both laughed.

“It still hurts,” I admitted. “Sometimes I see two empty chairs in my head and it feels like it just happened.”

“That might never completely go away,” she said. “But it doesn’t have to be the only picture you carry.”

Fireworks cracked overhead, bright against the dark sky. Kids squealed. Someone’s flag beach towel fluttered on the fence.

The next big shift came on a rainy Tuesday in October. I was at my desk at work, answering emails, when my phone buzzed. Mom.

I hesitated, then answered.

“Hey,” I said. “Everything okay?”

“No,” she said, and my stomach dropped. “The vet says…we’re there. It’s time. Her heart’s failing. They don’t think she’ll make it through the week without suffering.”

I closed my eyes. “I’m so sorry.”

“They asked if we want to be with her,” Mom said. “When they…you know. I don’t know if I can do it. I don’t know if I can let her go alone either.”

I heard Dad’s voice faintly in the background, then the muffled sound of him crying. The last time I’d heard him cry like that was at my grandmother’s funeral.

“Would you…come?” Mom asked. “I know it’s a lot to ask. I know we don’t deserve it. But I don’t want to do this without you. I don’t want to make another huge mistake with our family.”

I looked out my office window at the gray sky, the parking lot dotted with cars, the flag in front of the bank across the street whipping in the wind.

“I need to think about it,” I said. “I’ll call you back.”

She didn’t push. “Okay. We have the appointment at four. Just…whatever you decide, we love you.”

I hung up and sat there, my hands shaking on the keyboard.

Beth wasn’t available for an emergency session, but she replied to my panicked email with a short message: You get to choose what you can live with long-term. Not what earns you the “good daughter” badge today.

Tom came to my office. I hadn’t even asked; he just showed up with coffee, knowing my tells too well.

“If you don’t go, will you regret it?” he asked, leaning against my desk.

“I might,” I said. “If I go, I might resent them anyway. If I don’t go, I might resent myself.”

He nodded. “Both choices hurt. Which hurt feels more aligned with who you are now?”

I thought about the younger version of me who had stood in a white dress, staring at empty chairs. I thought about the current version of me, sitting in emergency vet waiting rooms by choice, building a life in a house with room for a future I still wasn’t sure about.

“I don’t want them to be alone,” I said finally. “Not for this. And I don’t want to become someone who closes every door because of one wound, no matter how big that wound was.”

So at 3:45 p.m., Tom and I walked into the same exam room where I’d first met the cardiologist months earlier. Muffin lay on a blanket on the table, a little gray around the muzzle, eyes cloudy but still tracking my parents.

Mom sat on one side of the table, Dad on the other. They both looked up when we came in, faces raw.

“You’re here,” Mom whispered.

“I’m here,” I said.

They brought in the vet, a soft-spoken woman with tired eyes, and explained the procedure. It was peaceful, painless. I’d heard all those words before, but sitting there with my hand on Muffin’s soft fur, feeling my parents’ grief vibrating through the room, I understood them differently.

When it was over, Mom folded in on herself, sobbing into Dad’s chest. He clung to her like a life raft. I stood there with my hand still on the empty space where a small heartbeat had been minutes earlier, tears running down my own face.

“I’m so sorry,” I said again, but this time it wasn’t about the years of resentment. It was about this moment, this loss.

On the drive home, my parents asked if we’d come by the house.

“We boxed up her toys,” Dad said quietly. “We thought maybe we could…put them away together.”

It felt strange to be part of a dog’s after-funeral, but it also felt like a chance to close a chapter that had been open too long.

Their house looked the same from the outside—same flag on the porch, same flowerbeds—but inside, little gaps stood out everywhere. The velvet dog bed was gone from the corner of the living room. The hook where her leash had hung near the back door was empty.

On the kitchen table sat a shoebox filled with toys and bandanas. The Instagram photos had been taken down from the fridge, replaced by a single picture of our family at Priscilla’s wedding.

“We’re going to plant a tree in the backyard,” Mom said. “Maybe put her collar at the base. We don’t want a shrine this time. Just…something living.”

We stood in the drizzle in their backyard, watching Dad dig a small hole near the fence. Mom placed the collar and a couple of favorite toys in before they set the sapling in place.

“Goodbye, troublemaker,” Dad murmured. “Thank you for the years.”

I thought about saying something, but the words felt private, between them and the dog who’d been both a wedge and a bridge in our relationship.

After we went back inside, Mom made tea without asking how I took it. She still remembered. We sat at the table with mismatched mugs, steam curling between us.

“I know we can’t fix everything,” she said, eyes red. “But I don’t want to waste whatever time we have left making the same mistakes. We want to show up for you. Really show up.”

“You have been,” I said. “For months now. I see it.”

Dad nodded. “We’re late to the game, but we’re here.”

The social consequences of all of this took on a different tone after Muffin died. For three years, our family group chat had been a place where people made joking references to my parents being “those dog people” under their breath. Now, condolences poured in.

So sorry for your loss 💔, Caleb wrote. She was a good girl.

She really was, I replied.

At Thanksgiving that year, Katie set one extra place at the edge of the table with a little paw-print place card and a candle. It was cheesy and tender and, somehow, exactly right.

“We lost a family member too,” she said when my parents’ eyes filled.

The grief, the reckoning, the slow rebuilding—they all mixed together into something that didn’t fit neatly into a category. It wasn’t just “forgiving” or “not forgiving.” It was living.

Time did its strange, inevitable work. Spring came, then summer again. Tom and I planted herbs in raised beds in our backyard, the ones Dad had helped us build. Mom texted me recipes and asked for pictures of how the basil was doing.

Sometimes, when we were all together—at birthdays, at Sunday dinners that actually happened, at random Tuesday night takeout—they’d talk about Muffin. But the stories were short, folded into larger conversations about work, about future vacations, about my cousin’s kids.

One evening in late June, as fireflies blinked over our lawn and the neighbor’s flag stirred lazily in the warm air, Tom and I sat on our back steps talking about the future.

“Have you thought more about kids?” he asked gently.

The question had hovered between us for years, something we never quite grabbed.

“Yes,” I said. “And no. I’m afraid of repeating patterns. Of my parents trying to use a grandchild to make up for everything. Of me swinging so far in the opposite direction that I smother the kid trying not to be them.”

Tom nodded. “That’s a lot to carry. But you’re not your parents.”

“I know,” I said. “I also know how much it hurt to feel like second place to a dog. I don’t want anyone in our house to feel like that. Ever.”

Beth and I dug into that in therapy—the difference between being guided by old wounds and being defined by them.

“You have data now,” she reminded me. “You’ve watched your parents change. You’ve watched yourself set boundaries and stick to them. You’re not the same person who stood in that chapel thinking you had no power.”

On the first anniversary of Muffin’s death, my parents invited us over for dinner.

“No big ceremony,” Mom promised. “Just dinner. Maybe we’ll look at a couple of pictures. That’s it.”

They’d framed one of the photos from our backyard tree-planting—a small sapling, four figures standing around it, heads bowed. It sat on a shelf next to our wedding album, the new one Mom had made.

“We don’t want to forget her,” Dad said. “But we also don’t want our house to be a museum of what we did wrong.”

We ate grilled chicken and roasted vegetables at their kitchen table, the same table where I’d once sat alone while Muffin’s bed occupied the place of honor in the living room.

At one point, Mom reached across and squeezed my hand.

“You know,” she said, “sometimes I think about your wedding and the number twelve. Twelve missed calls. It replays in my head like a countdown to the worst choice of my life.”

My throat tightened. “I think about twelve, too,” I said. “But also about every time you’ve shown up since. Those numbers are starting to balance each other out.”

She nodded, tears in her eyes. “That’s all we can hope for, I guess. To keep adding good numbers.”

Months turned into another year. The rawness of everything softened at the edges. The story of “my parents skipped my wedding for their dog” became something I could tell without my voice shaking, something I could choose to share or not depending on the context.

Sometimes at work, when colleagues swapped stories about complicated families over microwaved lunches, I’d offer a condensed version.

“My parents once missed my wedding for their Labradoodle,” I’d say.

The reactions were always the same—wide eyes, disbelieving laughter, a flurry of questions.

“Are you kidding?”

“What happened?”

“Do you talk to them?”

I’d explain the outlines: the obsession, the missed events, the revenge policy, the therapy, the reckoning. I always ended with the same line.

“We’re in a better place now,” I’d say. “It’s not perfect. But it’s real.”

Sometimes that was enough. Sometimes it opened doors for other people to talk about their own messy, unfinished family stories.

One afternoon, weeks after one of those lunch conversations, a coworker knocked on my office door.

“I made a vet appointment for our dog during my kid’s school play,” she said, her voice shaky. “I rescheduled as soon as I thought about your story.”

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

“Good,” I said. “Your kid will remember you being there.”

In quiet moments at home, I’d still find myself drawn to the fridge. To the flag magnet holding up the photo from Priscilla’s wedding. Me, Tom, my parents, my sister. All of us in one frame, smiling at a camera we actually showed up for.

That magnet had started as a joke—something cheap I stuck on a college dorm fridge because it came in a pack of four. Now it anchored some of the most important images of my life.

Sometimes, when I straightened it, I thought about how many versions of myself had stood in front of different fridges in different kitchens. The college kid with the magnet holding up exam schedules. The newly engaged woman staring at a picture of a dog in a sweater instead of a save-the-date. The angry newlywed clutching her phone, counting twelve missed calls. The homeowner with basil on the windowsill and therapy appointments in her calendar.

All of those versions of me deserved better than to be abandoned for a vet waiting room. I couldn’t go back and fix what they didn’t get. But I could take care of the person I was now.

The last time Beth and I talked about my parents, she asked a question that startled me.

“If you could go back to one moment and whisper something in your own ear,” she said, “which moment would you choose?”

I pictured so many scenes: the bridal suite with my half-curled hair, the chapel with the empty chairs, the living room with my thumbs hovering over excuses, the emergency vet waiting room.

“I think I’d pick the morning of my wedding,” I said. “Right after the phone call.”

“What would you tell yourself?”

“That their choice wasn’t a reflection of my worth,” I said. “That it was about their brokenness, not my value. That I was allowed to be furious and hurt and still build a good life anyway. And that one day, I’d stand in a different kitchen, in a different house, and feel…lighter.”

Beth smiled. “Sounds like you’re already telling yourself that now.”

On a random Saturday, almost three years after my wedding, I found myself alone in our kitchen again. Tom was out running errands. The house was quiet except for the hum of the fridge and the distant sound of a neighbor mowing their lawn.

I made my usual glass of iced tea, condensation forming a ring on the flag coaster. I looked at the photo on the fridge—the four of us in our wedding clothes at someone else’s ceremony, all actually there.

My phone buzzed. A text from Mom.

Brunch tomorrow? Our place. 11:30. No emergencies, no excuses. Just pancakes.

I smiled.

Sounds good, I typed. We’ll be there.

No policy, no revenge. Just a choice.

I set my phone down, took a sip of tea, and let the quiet settle around me. The story of my parents and their dog and my skipped wedding would always be part of me, stitched into the fabric of who I was. But it wasn’t the only story anymore.

If Muffin had once been the center of our family’s orbit, now she was a chapter—a messy, painful, strangely pivotal chapter that had forced all of us to decide who we wanted to be when love got tangled up with obsession.

And sitting there in my own kitchen, flag magnet holding up a picture of a family that actually showed up, I finally felt like the main character in my life again, not the understudy to a dog on a velvet bed.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load