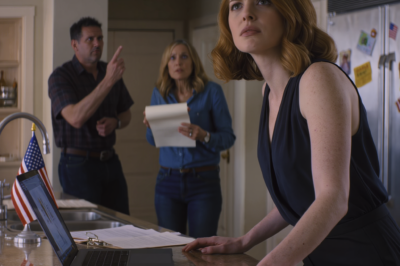

The night my husband disowned his entire family, the American flag magnet on his parents’ fridge was crooked.

It sounds like a strange thing to notice when your life is blowing up in real time, but sometimes your brain grabs onto tiny details so it doesn’t fall apart. That magnet had been there for years, holding up a faded school photo of my husband’s sister from seventh grade. Tonight the top corner sagged, the stripes tilting down toward a casserole warming on the counter.

Outside, July heat still clung to everyone’s clothes. Inside, the air-conditioning hummed; glasses of iced tea sweated circles onto Ruth’s good tablecloth. Sinatra played too softly from a Bluetooth speaker in the corner—his voice smooth, warm, pretending everything was normal.

It wasn’t. I knew that the second we walked through the door.

If motherhood gives you anything, it’s radar.

Not the fun kind that helps you find lost toys or the remote under the couch. The animal kind. The something in this room is wrong kind. That feeling hit me before we even sat down, like stepping into a house where the lights are on but the energy is off.

Ruth—my mother-in-law—swept over with a tight smile that never touched her eyes.

“Terra,” she said, kissing the air near my cheek. “You look… tired.”

“Hi, Ruth,” I replied, pretending not to hear the insult.

Gerald, my father-in-law, didn’t bother pretending at all. He gave Robert a curt nod, looked right through me, then down at Mia like she was a neighbor’s kid we’d brought by, not his granddaughter.

“Hey, kiddo,” he said. No smile.

Mia, seven years old, clutched her stuffed keychain to her chest—a sparkly unicorn she’d begged for with big eyes and two weeks of chore money. She whispered, “Hi, Grandpa,” in that careful, too-polite voice she used around people she didn’t trust.

The third person at the table, Jenna, looked like the only one enjoying herself.

She was Robert’s little sister by blood, but by personality she always felt like his third parent—a spoiled, permanently aggrieved third parent. Tonight she sat at the far end of the table, posture perfect, eyeliner sharp, holding a glass of iced tea like it was a prop. The look on her face reminded me of a cat who’d found something it shouldn’t and couldn’t wait to drag it into the living room.

Our daughter Mia slid into the chair beside me, legs swinging under the seat, humming under her breath, blissfully unaware of the way the air thickened around us. Robert took the chair across from me, eyes flicking from his parents to his sister to me like he was triangulating danger.

The room was too quiet. Not peaceful quiet—ready quiet.

We made it through the salad.

Ruth passed the bowl with the stiff politeness of a flight attendant in turbulence. Gerald corrected Mia on how she held her fork, as if that mattered more than anything else on earth. Jenna said nothing, but her fingers tapped, tap-tap-tap, on the edge of an envelope resting beside her plate.

That was the first time I noticed it.

Thick. Off-white. The kind of paper you don’t use for birthday cards or junk mail. My stomach twitched.

Ruth cleared her throat.

If you’ve ever been around someone who loves drama more than they love people, you know that particular throat clear. It’s not about clearing anything; it’s about calling the room to order.

“Jenna,” she said, smoothing her napkin. “Didn’t you have something you wanted to share with us tonight?”

She said “share” the way people say “confess.”

My stomach dropped.

Jenna pushed her chair back with a long, slow scrape against the hardwood. Her hand drifted to the envelope like it belonged to her, which, given the look on her face, it probably did.

“I do,” she said, voice trembling with excitement.

She stood, one hand braced on the back of the chair, the other casually cupping the envelope, eyes lit up with a kind of ugly anticipation. When she turned toward me, I knew whatever came next was going to be bad, but I still wasn’t ready.

She pointed straight at me.

“You,” she announced, like a prosecutor in a courtroom she’d built in her head, “are a cheater.”

For half a second, my brain reached for a reasonable explanation.

Maybe she meant the family board game we’d played last Thanksgiving where I’d “accidentally” moved my piece two extra spaces. Maybe she meant the step-count challenge in the family group chat that I kept forgetting to log. Maybe—

No. There was nothing playful in her face.

Before I could scrape together a single word, Jenna turned to Mia.

Our daughter. Seven years old. Pink headband with a crooked bow. Small carton of chocolate milk sweating beside her plate.

Jenna smiled.

“You’re not really ours,” she told her. “Robert isn’t your dad.”

The world dropped out from under the table.

Mia went silent. Her legs stopped swinging. The color drained from her face so quickly it was like watching a Polaroid reverse itself.

She looked at Robert as if he were the only solid thing left in a room that had just tilted. Then at me. Then back at him.

“Daddy?” she whispered. “What… what does she mean?”

I swear I heard my heart crack. Not metaphorically. An actual sound in my chest, a pop of pressure, like something had given way.

I opened my mouth, but the words knotted behind my teeth.

Then Gerald decided he hadn’t done enough damage just sitting there.

“Sweetheart,” he said in that flat, grandfather voice he liked to use when pretending he cared, “we’re not really your grandparents either. Not… biologically.”

Mia flinched like he’d slapped her.

I stood up so fast my chair scraped hard enough to make everyone jump. My vision narrowed, the edges of my sight dimming like a camera lens closing in.

I didn’t yell. I didn’t lunge for anyone’s throat. I just moved.

I unbuckled Mia from her chair, hands moving on their own. She came willingly, like her body already knew she needed distance before her mind caught up. She wrapped her arms around my neck, fingers digging in.

Behind me, there was a sharp smack as something hit the table.

The envelope.

“Here,” Jenna said, triumphant. “We got the proof. A paternity test. You don’t have to take my word for it. You can see for yourself how she played you.”

I didn’t look back, but I could feel Robert’s whole body shift.

Robert is not a loud man. He’s not the type to flip tables or punch walls. His default setting is patient. Controlled. The kind of guy who lets people merge in heavy traffic and always refills the office coffee pot.

But the air behind me changed.

In the hallway, away from their faces, Mia shook in my arms, small and stiff.

I kept walking.

I didn’t stop to grab my purse. I didn’t stop to look at anyone. I just walked until the dining room doorway was behind us, until we were halfway down the hall where Ruth’s framed family photos lined the walls. Robert as a boy in a Little League uniform. Jenna in braces. The four of them at some beach years ago, all sunburned and squinting.

Not a single picture of Mia.

I pressed my cheek to her hair. She smelled like baby shampoo and barbecue sauce.

In the dining room, Ruth’s voice rose, piercing and indignant.

“We did you a favor,” she snapped. “You needed to know.”

“It’s a paternity test!” Jenna said, almost giddy. “Open it, Robert. Come on. See for yourself. She’s been lying to you for years.”

“Go on, son,” Gerald added, smug. “You deserve the truth.”

Mia trembled in my arms. Her little fingers clutched the back of my shirt as if it were a life raft.

Then I heard Robert.

He didn’t sound broken.

He didn’t sound shocked.

He sounded… done.

“This,” he said, voice calm and controlled, “is the last time we will ever visit you.”

Silence. Heavy, stunned silence.

“What are you talking about?” Ruth sputtered. “You should be angry at her, not us.”

“We told you the truth,” Jenna snapped. “You’re welcome.”

“I cannot believe you did a DNA test behind my back,” Robert said, still in that eerie, level tone.

A beat.

“And I cannot believe you said any of this in front of a child.”

Another beat.

“You’re right about one thing.”

I held my breath without meaning to.

“You’re not her grandparents anymore.”

Someone gasped. A chair scraped. Someone muttered a curse. Another voice tried to talk over his, but Robert’s next sentence cut through all of it like glass.

“And I’m not your son anymore.”

The next few seconds felt like being underwater.

“We raised you,” Ruth hissed.

“You used me,” Robert replied.

“You’re overreacting,” Gerald said.

“You haven’t even opened the envelope,” Jenna threw in.

“I don’t need to,” Robert said. “Because yes, I know she isn’t biologically mine. I have always known. And my wife never cheated on me.”

The last sentence landed like a gavel.

He didn’t shout. He didn’t throw anything. He just placed the truth in the middle of the table like a card he’d been holding for years.

I closed my eyes in the hallway and exhaled. Not with relief—nothing about this felt relieving—but with something closer to recognition.

The secret was out. Not the secret of Mia’s conception—that had never felt dirty to me—but the secret of who his family really was.

There was more yelling. Faint, muffled. Someone said, “You lied to us.” Someone else said, “We had a right to know.” But underneath the noise, something else was happening. A shift. A realignment.

Robert’s footsteps approached.

He reached us in the hallway, eyes going straight to Mia’s tear-streaked face.

“Let’s go,” he said softly.

We left.

We didn’t slam the door. We didn’t deliver a mic-drop speech. Robert picked up the keys from the entryway table, I grabbed my purse without remembering how, and we walked out into the thick summer night.

The air smelled like cut grass and hot asphalt. Somewhere down the block, a dog barked. Someone’s TV flickered behind a curtain next door, the laugh track of a sitcom echoing through the quiet.

Mia clung to me all the way to the car. Robert opened the back door; I slid in with her instead of buckling her alone. She pressed herself into my side like she was trying to climb inside my skin.

Robert started the engine. The driveway lights reflected off his face, jaw clenched, eyes dry.

No one said anything on the ride home. Sinatra’s voice from the Bluetooth speaker inside the house faded behind us as we turned the corner.

If silence had a temperature, that car ride could have flash-frozen a lake.

Mia stared out the window, small and rigid, as we passed the same grocery store, the same gas station, the same playground we drove by every week. Only now the world outside felt sharper somehow, like the edges of everything had been outlined in black.

I watched her in the rearview mirror, waiting. For a meltdown. For questions. For anything.

She said nothing.

Robert’s hands gripped the steering wheel so hard his knuckles went white.

When we pulled into our own driveway, our little rental house looked exactly the same as it had when we left an hour earlier. Porch light on. Old grill on the back patio. Mia’s chalk drawings still ghosting the sidewalk from last weekend’s hopscotch game.

None of it matched what I felt inside.

Mia stepped out of the car slowly, clutching her unicorn keychain. Usually she’d run ahead, racing us to the front door. Tonight she hovered by my side.

Inside, she didn’t take off her shoes. She didn’t ask for dessert. She didn’t reach for the TV remote. She just stood in the hallway, eyes huge, waiting for someone to tell her which parts of her life were still real.

Robert and I exchanged a look.

Okay, that look said. This is where we stop being stunned and start being parents.

We sat with her on the couch, all three of us sinking into the worn cushions. I took her left hand. Robert took her right.

“Mia,” I said gently, “remember how we told you we wanted you for a really long time before you were born?”

She nodded once, eyes fixed on her knees.

“When Mommy and I were trying to have a baby,” Robert said, voice soft, “the doctors told us my body doesn’t make babies the regular way. So they helped us. They used a special kind of medicine and science to put you in Mommy’s tummy.”

“You grew inside me,” I added. “Just like any other baby. I felt you kick. I cried when I heard your heartbeat. We counted down the days until you got here.”

“You were always wanted,” Robert said. “Always loved. From the very beginning. You are my daughter, now and always. Nothing can change that. Not a test, not a piece of paper, not anything anyone says.”

She looked up at him, searching his face for cracks.

“And Mommy never cheated on Daddy,” I said, because that poison needed to be scrubbed out of the air immediately. “Daddy has always known exactly how you were made. He’s never had a single doubt.”

Mia’s lips parted, then closed. She swallowed.

“Jenna said… you’re not my real dad,” she whispered.

Robert’s fingers tightened around her hand. “I am your real dad,” he said. “Real doesn’t mean matching DNA. Real means the person who tucks you in and reads you stories and comes to your school plays and sits in the ER with you when you break your arm.”

“You never broke your arm,” I said, because my brain does weird things under stress.

“Metaphorically,” he said.

“Is that like a simile?” she asked automatically, finally sounding like herself for half a second.

“Sort of,” he replied.

She didn’t cry. She didn’t scream. She just nodded once, slowly, like she’d filed the conversation under “To be processed later.”

Then she slipped her hands out of ours, slid off the couch, and walked down the hall to her room.

The door clicked shut behind her.

Robert rubbed his face with both hands. “I don’t know if that was her accepting it or shutting down,” he said.

“Both,” I answered. “Probably both. Welcome to childhood trauma speedruns.”

We sat there for a long minute, listening to the soft hum of the air conditioner and the distant whoosh of a passing car.

Then Robert stood up.

“I need to do something,” he said.

He walked down the hall and into our small office, where his ancient desk held his work laptop, a dead succulent, and a mug full of pens Mia kept stealing. I followed, leaning in the doorway.

He sat down, opened his banking app, and stared at the screen like it was a test he’d finally decided to stop failing.

First click: cancel the recurring transfer to Ruth and Gerald. That monthly “help” that was basically a second mortgage we didn’t live in.

Second click: cancel the automatic tuition payment to the university. The one that came out to just under $1,000 every month. Twelve months a year. Twenty-four thousand dollars over two years.

Third click: deactivate the extra debit card he’d given Jenna “just for emergencies,” which somehow included boutique clothes, concert tickets, and DoorDash orders at 1 a.m.

“Terra,” he called.

“Yeah?”

“I’m cutting off everything,” he said. “All of it.”

“Good,” I replied. “I’d bake you a congratulations cake, but I’m not emotionally stable enough for frosting right now.”

He let out a short, shaky laugh. “This feels… weirdly healthy.”

“Boundary-setting,” I said. “We should put that on a T-shirt.”

He leaned back in the chair, exhaled like air was finally reaching the bottom of his lungs. “Honestly,” he said, “this is the first decision I’ve ever made about them that actually makes sense.”

The next morning was too quiet.

Not the peaceful, lazy Saturday quiet where cartoons echo from the living room and pancakes burn because someone got distracted. This was more like the hush after a storm when you’re not sure if it’s over.

Mia emerged from her room in unicorn pajamas, hair sticking up in the back. She clutched her stuffed animal, looked at us carefully, then asked if she could watch TV.

“Of course,” I said.

She curled up on the couch, eyes glued to the screen, body pressed into the corner like she needed a wall at her back. No questions. No comments about last night. Just an unspoken agreement that we were all pretending to be normal until we actually were.

Around noon, Robert’s phone lit up on the coffee table.

RUTH.

Then GERALD.

Then RUTH again.

He stared at it for a long second. When it buzzed a third time, he picked it up and hit speaker.

“How could you do this to us?” Ruth’s voice exploded through the room. “Your sister needs that money. You’re ruining her future. Tuition is due in two days. We can’t afford this without you.”

“I’m not paying anymore,” Robert said calmly.

“Be reasonable,” Gerald barked. “Jenna cannot stay in school without your support. You know how expensive it is.”

“I do,” Robert said. “I’ve seen every bill. I’ve paid every bill. That’s why I’m done. She’s twenty. She can apply for loans. Get another job. Take a semester off. Be an adult.”

“You can’t abandon your family,” Ruth cried. “What kind of son turns his back like this?”

“The kind whose family told his seven-year-old she doesn’t belong,” he replied.

There was a crackle of silence on the other end, like the sound had fallen off a cliff.

“You’re choosing her over us,” Ruth said, incredulous. “She’s twisted you against us, Robert. You owe us. After everything we’ve done for you.”

Robert ended the call.

Just like that. No warning. No “goodbye.”

I walked over and kissed his cheek. “I’m proud of you,” I said.

He looked surprised. “I’ve never done that before,” he admitted. “Hung up on them.”

“How does it feel?” I asked.

He exhaled, long and slow. “Like I just took off a forty-pound backpack I didn’t know I was wearing.”

Mia peeked around the edge of the couch, eyes big.

“Daddy?” she asked quietly. “Are Grandma Ruth and Grandpa Gerald mad?”

Robert crouched down so he was eye-level with her.

“They’re upset because they did something wrong,” he said. “Not because of you.”

She nodded like that made sense and went back to her cartoons, hugging her stuffed unicorn like it was a shield.

We didn’t get twenty minutes before someone pounded on the front door.

Not the tentative knock of a neighbor borrowing sugar. Not the frantic knock of an emergency. The heavy, rhythmic knock of someone who believes they are entitled to be let in.

Robert stood.

“I’ll get it,” I said.

On the porch stood Ruth and Gerald, side by side, faces drawn tight. Ruth’s lipstick was smudged at one corner; Gerald’s tie was slightly askew. That told me everything I needed to know—they had rushed over without giving themselves time to fully put on their masks.

“Let us in,” Ruth said. It wasn’t a request.

I opened the door just wide enough that the neighbors across the street couldn’t hear every word. They brushed past me without waiting, walking into our hallway like this was still their home too.

Robert stepped into the doorway from the living room, shoulders squared.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

“You hung up on us,” Gerald said, as if that were a crime.

“Yes,” Robert replied.

“That’s how you talk to your parents now?” Ruth demanded.

“That’s how I talk to anyone who crosses a line,” he said.

Ruth folded her arms, chin tilting up. “We want an explanation. Right now.”

“Okay,” Robert said. “I canceled the tuition payments. I’m not paying anymore.”

“You what?” Gerald blinked.

“You heard me,” Robert said.

“You can’t do that,” Ruth snapped. “She needs that money. You know that.”

“She’s twenty,” Robert repeated. “Plenty of adults figure out how to pay for school.”

“That’s easy for you to say,” Gerald scoffed. “You had help.”

“From who?” Robert asked, genuinely curious. “Because it wasn’t either of you. I paid my own way through community college. I worked nights. I took out loans.”

“Don’t be dramatic,” Ruth said. “We supported you in our own ways.”

“You criticized my wife every chance you got,” Robert shot back. “You treated her like she was stealing from me when she was paying half our bills. You treated Mia like a visitor in my own house. And last night you told my daughter she doesn’t belong in her family.”

“Jenna made a mistake,” Ruth interrupted. “She spoke out of turn. She was upset. She—”

I stepped closer. “She told my child that her father isn’t her father,” I said, voice shaking. “She told her she isn’t part of this family. That’s not a slip. That’s cruelty. And you all sat there and watched.”

“She didn’t mean it,” Ruth insisted. “She was emotional. We were all emotional.”

“And you backed her up,” Robert said. “You called it the truth. You dropped a DNA test on the table like it was a party favor.”

“You lied to us,” Gerald shot back. “You should have told us. We had a right to know she isn’t our granddaughter biologically.”

There it was. The sentence that cracked everything fully open.

My breath caught. Because behind us, down the hallway, I heard a soft footstep.

“Daddy?” Mia’s small voice trembled.

She stood at the edge of the hall, bare feet on the hardwood, damp hair from her bath curling around her face. She wore her favorite rainbow T-shirt, the one with a tiny stain near the hem from a popsicle months ago.

Her eyes flicked from Ruth to Gerald to Robert to me.

“They said I’m not their granddaughter,” she whispered. Her voice broke on the last word.

I went to her, body moving before my brain. Her legs buckled; I scooped her up as tears spilled down her cheeks. She clung to my shirt, sobbing into my collarbone.

Ruth took a step forward, reaching out. “Sweetheart, you misunderstood. We didn’t mean—”

“Don’t,” Robert said.

He didn’t raise his voice. It didn’t need volume. It had weight.

He placed a hand gently on Mia’s back, eyes never leaving his parents.

“You need to leave,” he said.

“Robert, listen,” Ruth started.

“I’m done listening,” he replied.

“We came here to fix this,” Gerald said.

“No,” Robert said. “You came here to make yourselves feel better.”

“You are being ridiculous,” Ruth snapped. “This is not how a son speaks to his parents.”

“This is how a father protects his child,” Robert said.

The sentence sat between them like a line drawn in permanent marker.

“You’re going to throw away your family over a misunderstanding?” Ruth demanded.

“You threw us away,” Robert said quietly. “The second you made my daughter believe she doesn’t belong. That’s not a misunderstanding. That’s a choice.”

“If we walk out that door,” Gerald said, voice hard, “we won’t be coming back. And you won’t either.”

Robert nodded. “You’re right.”

He opened the front door and stepped aside.

“Please go,” he said.

Ruth stared at him, disbelief twisting her features. For a moment, I saw the calculation in her eyes—whether tears, anger, or guilt would get her what she wanted.

None of them worked.

She walked out, shoulders stiff. Gerald followed, jaw clenched. They got into their sedan, backed out of our driveway, and drove away without looking back.

Robert closed the door. Locked it. Checked the lock twice.

When he turned around, the anger in his face was gone. What replaced it wasn’t relief. It was something heavier. Final.

He took Mia from my arms and held her against his chest. She grabbed handfuls of his T-shirt, still crying.

“It’s okay,” he whispered into her hair. “You’re okay. You’re my girl. Always. No matter what anyone says.”

She cried until her breath turned hiccupy and her body sagged against him, exhausted. He carried her to her room and sat on the edge of her bed, holding her until she finally fell asleep, fingers still knotted in his shirt.

Some choices don’t need to be justified. They explain themselves.

Later, when the house was quiet and the only light came from the hallway nightlight shaped like a little moon, we stood in Mia’s doorway and watched her breathe.

Robert reached for my hand and threaded his fingers through mine.

“This isn’t the end of it,” he murmured.

“I know,” I said.

He was right. It wasn’t.

The week that followed was quieter than I expected.

No more pounding on the door. No more calls after that initial barrage. Just… absence. A big, echoing absence where their demands and constant commentary used to be.

Mia didn’t ask about Ruth or Gerald. She didn’t bring up what she’d heard again. She seemed to decide, in the practical way kids sometimes do, that if we weren’t talking about it, neither was she.

But the weight of it hung there, in the way she asked for extra hugs, in how she lingered at bedtime, in the way she watched Robert when she thought he wasn’t looking, as if checking to make sure he was still here.

One evening, we were making dinner—tacos, because I needed something simple that everyone liked. Robert stood at the stove, brow furrowed, carefully browning ground beef. I chopped tomatoes and tried not to cut my fingers.

Mia wandered into the kitchen, solemn.

“Do we still have to go to Grandma Ruth’s Sunday lunches?” she asked.

Robert froze, spatula hovering over the pan.

I held my breath.

“Because I don’t want to pretend to like her meatloaf anymore,” Mia added, dead serious. “It tastes like old socks.”

I choked on a laugh, coughing into my sleeve. Robert let out a small, tired chuckle.

“No,” he said. “We don’t have to go to Grandma Ruth’s anymore.”

“Good,” Mia said, satisfied. “Can we have tacos every Sunday instead?”

“Taco Sundays,” Robert said. “It’s official.”

Sometimes healing doesn’t arrive as a grand epiphany. Sometimes it looks like choosing tacos over a woman who made you feel small.

Evenings settled into a new routine. Mia colored at the dining table while Robert answered emails and I tried to focus on my own work. She’d wander over and lean against his arm, watching him type.

“What are you doing?” she’d ask.

“Writing boring grown-up emails,” he’d reply.

“Does your boss know you’re my dad?” she asked one night, voice casual.

“Everyone knows I’m your dad,” he said.

“Good,” she replied, going back to her crayons. She drew our family over and over—three figures under a crooked sun. Sometimes a cat we didn’t have yet. Never Ruth. Never Gerald. She didn’t even draw Jenna at first.

I didn’t push. Kids process things in ways adults can’t always see. Her pictures told me enough.

A week passed. No calls. No texts. No cars slowing in front of our house.

Then, Saturday morning, just as Robert was tying Mia’s sneakers for a library trip, there was a knock at the door.

Not pounding. Not entitled. Just… hesitant.

Robert and I exchanged a look.

“I’ll get it,” I said.

I opened the door to find Jenna on the porch, holding a small bakery box tied with red-and-white twine. Her eyes were red-rimmed; her shoulders—usually set in a confident line—slumped.

For the first time since I met her, she looked unsure of herself.

“Hey,” she said, voice thin. “Can I talk to you both?”

Robert stepped beside me. His jaw tightened automatically.

“We’re about to head out,” he said.

“It won’t take long,” she promised, clutching the box like it might float away.

We let her in.

She hovered just inside the living room, glancing at the couch, the family photos, the toys in the corner, like she’d never really seen our house before—only judged it.

“I… I came to apologize,” she said, tripping over the word. She held out the bakery box like an offering. “I brought cake. From that place downtown you like.”

Her hands were shaking.

“I really didn’t know,” she said. “If I had known the truth, I would never have said what I said to Mia. Not like that. Not in front of her. That was… that was horrible. I am… I’m so sorry.”

Her voice cracked on “sorry,” and for a second I saw a scared kid under all the entitlement.

Robert nodded once. His face didn’t soften, but it didn’t harden more either.

“We accept your apology,” he said.

Jenna’s expression flickered. Relief. Panic. Something like hope.

“Is Mia here?” she asked. “I want to apologize to her too.”

“No,” I said. “And she doesn’t need any more confusion right now.”

Jenna nodded quickly. “Right. Yeah. That makes sense.”

Silence stretched out between us.

If this had been any other time in her life, she would’ve filled it with jokes or complaints. Instead, she grabbed for something else.

“I also wanted to ask…” She swallowed, eyes darting everywhere but our faces. “If you could still help with tuition. Just for this semester.”

There it was. The old script.

“I can’t afford it,” she said quickly. “Not even close. If I don’t pay, they’ll drop me. I’ll lose my spot. I don’t know what to do. Could you maybe… loan it to me? Just this once? I’ll pay you back when I graduate, or when I get a job, or—”

“No,” Robert said.

The word landed like a hammer.

Jenna blinked. “What?”

“No,” he repeated. “I’m not paying anymore.”

“I get that you’re mad,” she rushed on. “I do. And it’s complicated. But maybe just this semester? Just to get me through the transition? I’m applying for scholarships, and I’m picking up extra shifts, but I can’t make it in time and—”

“No,” he said again.

Her face crumpled.

“Please,” she whispered. “I can’t drop out. You don’t understand. No one else can help me.”

“I understand perfectly,” Robert said. “You’re an adult. Adults figure things out. They apply for loans on time. They get jobs. They adjust when things change.”

“I didn’t mean to hurt anyone,” she said, tears spilling now. “I didn’t know. I swear I didn’t.”

“That’s exactly the problem,” Robert said. “You didn’t know. Because you never asked. You never thought about what it would do to a seven-year-old to hear those words. You never thought about anyone but yourself.”

“I said I was sorry,” she whispered.

“And we accepted your apology,” I said. “But an apology isn’t a coupon you redeem for more money.”

She winced.

“I can’t believe you’d let me fail,” she said quietly. “After everything.”

“After everything,” Robert echoed. “After twenty-four thousand dollars in tuition. After years of covering Mom and Dad’s bills. After everything my daughter went through because of what happened at that table. Yes. After everything.”

“Is there anything I can do?” she asked. “Anything that would change your mind?”

“No,” he said simply.

Her shoulders collapsed inward. For the first time, she looked small in our living room.

She turned toward the door, bakery box still clutched in both hands. Her fingers dug into the cardboard, leaving little dents.

At the threshold, she paused and looked back, eyes shiny.

“I never thought you’d choose her over us,” she said, voice barely audible.

Robert frowned, like she’d spoken a language he didn’t understand.

“She’s my daughter,” he said. “There was never a choice.”

Jenna nodded once, sharp and defeated, and stepped out into the sunlight.

Robert closed the door. Locked it. Leaned his forehead against the wood for a second, as if it could hold him up.

“We did the right thing,” I said.

“I know,” he murmured. “I just didn’t expect it to feel like this.”

“Like what?”

“Like I finally grew up.”

Six months later, our life looked boring from the outside.

No explosive family dinners. No emergency Venmo transfers. No Sunday lunches where I had to psych myself up in the car like I was about to go onstage.

Robert’s entire paycheck stayed in our household now. Every dollar. We paid our bills on time. We built a tiny emergency fund. We even opened a savings account for Mia with a hundred dollars in it and let her see the number.

“Is that a lot?” she asked, eyes wide.

“It’s a start,” Robert said. “It’s yours.”

She drew a picture of the three of us and taped it to the fridge next to the printed account statement. No one else.

As for Ruth and Gerald, we heard about them through the grapevine.

They’d been so sure Robert would cave that they’d put off helping Jenna apply for loans. When the payment deadline hit, and our money didn’t appear, they scrambled. Emergency personal loan. Then another. Then a refinance on their house that had seemed like such a comfortable sure thing a year ago.

Now they were buried. Not just in debt, but in the consequences of their own choices.

Jenna took on extra hours at her part-time job—late-night shifts at a diner near campus, weekend hours at a clothing store. She posted vague complaints on social media about “fake people” and “family who abandon you when you need them most,” without naming names.

Robert saw them once when a mutual acquaintance screenshotted a post.

He stared at it for a long moment, thumb hovering over the screen, then locked his phone and slid it face-down on the table.

“I’m not taking that bait,” he said.

I believed him.

But just because the noise stopped didn’t mean the story did.

One afternoon in October, I got a call from Mia’s school.

“Hi, Mrs. Carter,” her teacher, Ms. Lang, said. “Do you have a minute?”

My heart did that automatic little stutter it always does when a teacher calls. “Is everything okay?” I asked, already bracing.

“Mia is fine,” Ms. Lang said quickly. “She’s actually great. I just… wanted to touch base about something that came up during a project.”

They were doing family trees.

Of course they were.

“She was very clear in her assignment,” Ms. Lang continued. “She listed you and Robert as her parents. She drew grandparents on your side. But she left the other side blank except for a note that said, ‘They’re not safe.’”

My throat tightened.

“I didn’t question her in front of the class,” Ms. Lang said. “I just told her she could share as much or as little as she wanted. But I wanted you to know.”

“Thank you,” I said. “We had… a situation with my husband’s family over the summer. They said some very harmful things to her. We went no-contact for our safety and hers.”

“I am so sorry,” Ms. Lang said. “Mia is a wonderful kid. Kind, helpful, very bright. If you ever want to come in and talk about how we can support her, my door is open.”

“Thank you,” I repeated, meaning it.

That night at dinner, I brought it up gently.

“So, I heard you’re working on family trees,” I said, scooping mashed potatoes.

Mia shrugged, stabbing a green bean. “We had to draw our families.”

“How did that feel?” Robert asked.

She considered. “Confusing,” she said. “But also easy.”

“How can it be both?” he asked.

“The confusing part is that I know Grandma Ruth and Grandpa Gerald exist, but they’re mean,” she said frankly. “The easy part is I don’t have to draw them.”

I blinked hard.

“I wrote that they’re not safe,” she added, casual. “That’s true, right?”

“Yes,” Robert said immediately. “That’s true.”

“Okay,” she said, satisfied. “Ms. Lang said I could draw churros on that side if I wanted.”

“Churros?” I asked, laughing.

“They’re my favorite,” she said. “They make me feel happy. I think that counts.”

So Mia’s family tree had us on one side and churros on the other.

Honestly? Could’ve been worse.

In November, Robert and I finally did something we’d been circling around for months: we found a therapist.

Not for Mia—not yet; her school counselor was checking in with her regularly, and she seemed steady—but for us.

Our couples therapist was a woman named Dr. Warner who had kind eyes and a no-nonsense way of calling out our patterns without making us feel stupid. Her office had a framed print of a tree and a bowl of blue glass stones on the coffee table.

On our second session, she asked, “How long do you think you’d been saying yes to them when you meant no?”

Robert stared at the stones.

“My whole life,” he said.

“That’s a long time to train your nervous system to believe no is dangerous,” she said gently. “It makes sense that your body feels shaky now that you’re using it.”

“I still feel guilty,” he admitted. “Even after what they did. I still hear my dad’s voice asking how I could do this to them.”

“What do you hear when you imagine Mia at twenty, asking why you didn’t protect her?” Dr. Warner asked.

He closed his eyes. “I hear her say, ‘Why didn’t you choose me?’”

“And what did you do this summer?” she asked.

“I chose her,” he said.

“Say it again,” Dr. Warner said.

“I chose her,” he repeated.

“And that,” she said, “is you being the father you wish you’d had.”

We left those sessions exhausted but lighter, like someone had taught us how to walk without dragging chains.

The holidays came and went.

We stayed home on Thanksgiving. Just the three of us. No turkey the size of a toddler, no passive-aggressive comments at the table. We made roasted chicken, mashed potatoes, and frozen green beans Mia insisted on stirring.

She went around the table, asking what we were thankful for.

“I’m thankful for tacos,” she said.

“I’m thankful for both of you,” Robert said.

“I’m thankful for boundaries,” I muttered.

“What are boundaries?” Mia asked.

“Fences for your feelings,” I said. “They tell you where you end and someone else begins.”

She nodded thoughtfully. “Then I’m thankful for those too.”

In December, we got exactly twelve Christmas cards in the mail.

One from my parents. Two from coworkers. A handful from friends. None from Ruth and Gerald.

The absence didn’t hurt as much as I expected. It just felt… accurate.

On Christmas morning, Mia opened a bike, a stack of books, and a set of art supplies. She grinned so hard her cheeks hurt.

“Did Santa bring Grandma and Grandpa presents?” she asked abruptly.

The question landed in the living room with a soft thud.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “We’re not in their house, so we can’t see.”

She considered this.

“I hope he brought them something small,” she decided. “Like a broom. For cleaning up their meanness.”

Of all the prayers I’ve ever heard, that one felt closest to an answer.

In January, everything seemed to settle into our new normal.

Then, in February, my phone lit up with a number I didn’t recognize.

“Hello?” I answered cautiously.

“Is this Terra Carter?” a woman’s voice asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“I’m calling from St. Vincent’s Hospital,” she said. “Your husband’s father, Gerald Carter, listed Robert as his emergency contact. He was admitted today after a cardiac event. He’s stable at the moment, but we’re trying to reach next of kin.”

The room tilted.

“Thank you for letting us know,” I said automatically. “We’ll… we’ll call you back.”

I hung up and stared at my phone.

Robert was at the kitchen table, helping Mia with math homework. Their heads bent over the worksheet, pencils tapping.

“Who was that?” he asked.

“St. Vincent’s,” I said. “It’s your dad. He had… something. They said ‘cardiac event.’ They listed you as emergency contact.”

Robert’s face went still.

They had disowned him as a son, but kept his name on their paperwork.

Of course they had.

“What do you want to do?” I asked.

He stared at nothing.

“I don’t know,” he said honestly.

We sat with it. The history. The harm. The reality that people are rarely just one thing.

“I don’t want to see him,” he said eventually. “I don’t want to walk into that room and let them perform being my parents again.”

“You don’t have to,” I said.

He nodded slowly.

“But I don’t want it on my conscience that I ignored a hospital call,” he added. “I’ll call them. I’ll tell them to contact my mom instead.”

He did.

He called the nurse station, confirmed that his father was stable, and gave them Ruth’s number.

“I’m not able to come in,” he said. “Please contact his wife. She’s his primary family.”

The nurse sounded surprised, but professional. “We will,” she said.

He hung up, exhaled, and watched Mia draw little hearts in the margin of her math sheet.

“That was the right call,” I said quietly.

“Maybe for the first time in my life,” he replied.

We found out later—from a cousin, not from them—that Gerald recovered, grouchier than ever. At some point, Ruth complained loudly that Robert “didn’t even come to the hospital,” like the concept of natural consequences had never occurred to her.

Spring came. Mia turned eight. We threw her a birthday party at a park, invited her classmates, served pizza and juice boxes, and watched her run around the playground with frosting on her face.

No one missing. No one needed.

For her wish, she closed her eyes over eight flickering candles and said, “I wish our family stays like this forever.”

I didn’t cry. Much.

Years passed. Slow and fast at the same time, the way they always do when you’re raising a child.

Mia lost teeth, learned to ride that bike, moved from chapter books to novels. She joined the school choir, hated soccer, loved art camp. We had flu seasons, school projects, scraped knees, late-night talks about friendship drama.

Sometimes, in small moments, the past would surface.

Once, when she was eleven, she came home from health class and said, “We watched a video about DNA and genes, and how you get half from each parent.”

“Okay,” I said, trying to keep my voice even. “How did that feel?”

“Weird,” she said. “But also kind of… cool. Like, I’m made of a lot of people.”

“That’s one way to look at it,” I said.

“I raised my hand and asked if a dad who doesn’t share DNA is still a real dad,” she continued. “And the teacher said, ‘Of course. Families are made in lots of different ways.’”

“What did everyone else say?” I asked.

“Nothing,” she said. “No one cared. Evan said his parents are divorced and he has three grandmas. So I felt pretty normal.”

“I’m glad,” I said.

She studied me. “You and Dad chose me, right?”

“Every single day,” I said.

She smiled, satisfied, and went to her room with a sketchbook under her arm.

When she was thirteen, there was a knock on the door one Sunday afternoon.

Gentler than Ruth’s. More familiar than a stranger’s.

I opened it to find Jenna standing there.

Older. Tired. Hair in a messy bun. No makeup. No performance. Just… human.

“Hi,” she said.

“Hi,” I replied cautiously.

“I’m not here to ask for money,” she said, before I could even think it. “I swear.”

I didn’t move, but I also didn’t slam the door, which was progress.

“I brought something,” she said, holding up a small manila folder. “And I wanted to ask if you’d give it to Mia. When you think she’s ready.”

“What is it?” I asked.

“A letter,” she said. “For her. And copies of… some things.”

She handed it to me. Inside were printed emails. Screenshots. A typed letter with her shaky signature at the bottom.

“What is all this?” I asked.

“Proof,” she said. “That she didn’t do anything wrong. That your marriage is real. That I was… wrong. For a long time.”

I flipped through the pages. One email from Ruth to a cousin, nasty and detailed, calling me names and implying I’d trapped Robert. Another from Gerald complaining about “having to pay” for a granddaughter who “isn’t even blood.” A screenshot of a text thread where Jenna had defended us and been shut down.

“I started therapy,” she said quietly. “A couple of years ago. Turns out, growing up being told the sun rises and sets on you doesn’t actually make you happy. It just makes you selfish. And lonely.”

I looked up.

“I’m not asking you to forgive me,” she said. “I just… I don’t want Mia to think your marriage was ever a lie. Or that I still believe what I said that night.”

“Why now?” I asked.

“Because I’m going back to school,” she said. “Community college this time. Working full-time. Paying my own way. It’s hard. But it feels… honest. And I realized I don’t want to keep telling myself the story Mom and Dad always told: that everyone who doesn’t give us what we want is evil.”

She swallowed.

“You were right,” she said. “An apology isn’t a coupon. I just wanted to leave you with something that might help her someday. When she asks questions.”

Behind me, I heard Mia’s voice.

“Mom? Who is it?”

I turned my head. She stood at the end of the hall, taller now, hoodie sleeves half-covering her hands.

Her eyes flicked to Jenna. Then to the folder in my hand. Then back to Jenna.

“Hi,” Jenna said softly.

Mia stared for a beat. Then she stepped forward.

“I remember what you said,” she said. No tremor in her voice this time. “I remember how it felt. Like my stomach was gone.”

Jenna’s face crumpled.

“I know,” she said. “I will regret that for the rest of my life.”

Mia considered her.

“Are you still mean?” she asked.

Jenna let out a wet, startled laugh. “Less,” she said. “I’m working on it.”

Mia nodded, like that was an acceptable answer.

“You don’t get to be in my life,” she said. “But you can leave that for my mom. And if I ever want to read it… maybe I will.”

Jenna nodded, tears slipping down her cheeks.

“I hope you have a good life,” Mia added. “Just… far away from mine.”

It was brutal. It was honest. It was a boundary.

“I hope you have a great one,” Jenna said. Then she left.

I closed the door.

Mia leaned against it, exhaling.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she said. “Weirdly.”

“Do you want to talk about it?” I asked.

“Not yet,” she said. “But… I want to go sit with Dad.”

We found him on the couch with a book, reading glasses perched on his nose in a way that still made me melt a little. Mia crawled into the space beside him like she’d been doing since she was small, tucking herself into his side, head on his shoulder.

“Hey, kiddo,” he said, automatically wrapping an arm around her. “Everything okay?”

“Yeah,” she said. “Just checking something.”

“What’s that?” he asked.

“That you’re real,” she said.

He smiled, eyes going glassy.

“I’m very real,” he said. “Unfortunately that means I snore.”

“I know,” she said. “I can hear you through the wall.”

She reached up and poked his cheek. “Definitely real.”

Years later, when Mia was getting ready to leave for college—her own college, chosen by her, visited together, financial aid forms filled out months in advance—we stood in the kitchen, surrounded by boxes.

On our fridge, held up by a magnet shaped like an American flag I’d bought at Target to replace the mental image of the crooked one at Ruth’s, was a photo of the three of us from her high school graduation. She wore her cap crooked; Robert’s tie was slightly off; my mascara had smudged from crying.

“Hey,” she said, opening the fridge for a soda. “Do you ever wonder what would’ve happened if Dad had opened that envelope?”

The question came out of nowhere and everywhere. It had been hovering for years.

“Not really,” I said. “Because I already know.”

“What?” she asked.

“He would’ve seen numbers that didn’t match,” I said. “And it wouldn’t have changed anything.”

She nodded. “I think you’re right.”

She popped the soda tab, took a sip, then looked at the photo again.

“People at school talk about ‘found family’ a lot,” she said. “Half my friends have step-parents or adoptive parents or weird complicated situations. It makes me mad that anyone ever tried to make me feel like I didn’t have the real thing.”

“You always had the real thing,” I said. “You still do.”

She smiled.

When she left for campus two weeks later, we helped carry boxes up three flights of stairs. Robert fixed her wobbly bed frame with a multitool. I labeled drawers. We met her roommate and her roommate’s nervous parents.

Before we left, she hugged us both so hard I could feel her heartbeat.

“You guys did a good job,” she said, surprising me.

“At what?” I asked, amused.

“Being parents,” she said. “Even when your parents sucked.”

I laughed, then cried, then laughed again.

On the drive home, the passenger seat felt too empty. Robert kept one hand on the wheel, the other resting palm-up on the center console like it was waiting. I laced my fingers through his.

“Do you ever think we went too far?” I asked quietly. “Cutting them out completely?”

He thought about it.

“Sometimes,” he said. “In the beginning. When the guilt was louder than the peace.”

“And now?” I asked.

He glanced at me, then back at the road.

“Now I think it took me thirty years to realize you’re allowed to protect your family even if it makes other people uncomfortable,” he said. “I think walking away was the first time I chose being a dad over being a son.”

He squeezed my hand.

“And I think,” he added, “that every time Mia chooses herself, a little piece of that night gets rewired.”

We stopped at a gas station on the way home. While he filled the tank, I went inside for snacks. At the register, there was a display of little magnets.

One was a tiny American flag.

I picked it up, turned it in my fingers, thinking of that first crooked magnet on Ruth’s fridge, all those years ago. Thinking of the way I’d stared at it while my world broke open.

Then I bought it.

At home, I stuck it straight on our own fridge, right above Mia’s old family drawings. Not crooked. Not covering anything.

Just… ours.

So what do I think, now that the dust has settled, the loans have come due, and our daughter knows exactly who she is?

I think Robert didn’t go too far.

I think, after a lifetime of being told he owed his parents everything, he finally went far enough.

When you spend eighteen years raising a child, you get used to the noise.

The thud of a backpack dropped by the door, the slam of a bathroom cabinet, the endless soundtrack of music leaking from a bedroom, the late-night fridge raiding. After we dropped Mia off at college, the quiet in our house felt like an extra piece of furniture I kept bumping into.

The first week, I kept setting an extra plate at dinner.

By the second week, I stopped opening her bedroom door every morning just to make sure she was still breathing. The room stayed exactly the way she’d left it: posters on the wall, fairy lights twisted over the headboard, a mug on the nightstand with a dried ring of hot chocolate at the bottom.

Robert threw himself into work and hobby projects, because that’s what he does when he doesn’t know how to sit still with his feelings. He built a bookshelf he didn’t need. He reorganized the garage twice. He considered repainting the kitchen, then didn’t.

One evening, I came home from work to find him standing in front of the fridge, staring at the little American flag magnet I’d bought years ago to replace the ghost of the crooked one at his parents’ house.

“You okay?” I asked, hanging my keys on the hook.

He tapped the magnet lightly. “Just thinking,” he said.

“Dangerous habit,” I replied.

He smiled, but it didn’t quite reach his eyes. “Do you ever wonder what would’ve happened if I’d stayed?” he asked.

“At your parents’?” I said. “Or in denial?”

“Both,” he said.

I thought about it. About the girl who might have grown up half-believing she was temporary. About the man who would have kept writing checks and swallowing his anger until it calcified into something ugly.

“I think,” I said, “you would’ve gotten really good at pretending. And really bad at sleeping.”

He let out a breath. “Probably.”

The phone buzzed on the counter. A text from Mia popped up on the screen.

MIA: they have a cereal bar in the dining hall that’s open until MIDNIGHT. this is the life

MIA: also my roommate has never seen The Goonies??? should I file a report

Robert’s face softened in a way I never get tired of.

“You can call her,” I said. “You don’t have to pretend you’re not refreshing her texts like the weather app.”

He rolled his eyes, but he picked up the phone.

Life settled into this new shape.

We visited her on long weekends, brought groceries she didn’t need, fixed things that weren’t really broken. She came home for Thanksgiving, for winter break, for spring break with a duffel bag and a pile of laundry that could’ve clothed a small village.

One Christmas, her second year of college, she came home with something else.

A boyfriend.

“His name is Eli,” she said, plopping onto the couch. “He’s on the debate team. He’s annoyingly good at it. Please don’t make it weird.”

“We don’t make things weird,” I lied.

Robert raised a hand. “I absolutely make things weird,” he said.

Eli came for dinner one night. Skinny, nervous, with a mop of dark hair and the kind of politeness that made me like him instantly. He shook Robert’s hand a little too hard, called me “ma’am,” and complimented the casserole twice.

“So, Eli,” Robert said over dessert, “what are your intentions with our Mia?”

I kicked his ankle under the table. Hard.

Eli blinked. Then he caught the glint in Robert’s eye and relaxed a little.

“Fair ones,” he said. “Very fair. And long-term, hopefully. Respectful. I can draft a bullet-point list if you’d like.”

Mia groaned. “Please don’t encourage him,” she said.

Later that night, after they’d left to meet friends and the house was quiet again, Robert sank onto the couch beside me.

“Do you think her grandparents know she’s in college?” he asked quietly.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I haven’t heard anything. Have you?”

He shook his head. “Just the occasional update from cousin Sam on social media. Mostly about Dad complaining the world has gone soft and Mom posting cryptic Bible verses.”

“Same as ever,” I said.

“Sam said Jenna finished her degree,” he added. “Took her a while. Lots of breaks. Paid her own way, I guess.”

“Therapy, too,” I said. “At least, last we heard.”

He nodded slowly. “I still see her sometimes. In my head. Standing on our porch with that cake and that desperate look.”

“People can change,” I said. “Doesn’t mean we have to put ourselves back in their blast radius.”

He nodded, but his face stayed troubled.

The thing no one tells you about going no-contact is that the absence doesn’t erase history. It just gives you enough space to see it clearly.

A few months later, we got another call from St. Vincent’s Hospital.

This time it wasn’t a nurse from the cardiac unit. It was someone from oncology.

“Mr. Carter,” the woman said when Robert picked up. “We have your mother listed as a patient here. She gave your name as her son. We wanted you to be aware of her diagnosis.”

He went very still.

“What diagnosis?” he asked.

“Stage four lung cancer,” the woman said gently. “She’s declined some forms of treatment. She’s receiving palliative care several days a week.”

He thanked her, hung up, and sat very quietly at the kitchen table.

I watched him, hands wrapped around my mug like it was an anchor.

“What are you thinking?” I asked.

He stared at the grain of the wood. “I’m thinking,” he said slowly, “that this is exactly the kind of thing she would’ve used to pull me back in. And I’m thinking I don’t know what the right thing is.”

“There isn’t one right thing,” I said. “There’s your right thing. And hers. They might not match.”

He rubbed his forehead. “If I don’t go see her, does that make me heartless?” he asked. “If I do go, am I betraying everything we decided?”

“There’s another question,” I said. “If you don’t go, can you live with it? And if you do go, can you protect yourself?”

He didn’t answer right away.

“Let’s tell Mia,” he said finally. “She deserves to know.”

We called her that night. Her face appeared on the screen, hair in a messy bun, fairy lights glowing behind her.

“Hey, old people,” she said. “What’s up?”

“We have… some news,” Robert said. “About Grandma Ruth.”

Her eyes narrowed. “Is she okay?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “She has cancer. Late stage.”

Mia’s expression flickered—surprise, then something more complicated.

“Oh,” she said. “Wow.”

“We don’t know how much time she has,” he said. “We don’t know if she wants to see us. The hospital just called to let me know because she put my name down.”

“Of course she did,” Mia muttered.

“You don’t have to do anything with this information,” I said. “We just didn’t want to hide it.”

She stared off to the side for a second, then back at us.

“Do you want to see her?” she asked Robert.

“I don’t know,” he said honestly. “Part of me feels like I should. Part of me wants to never be in the same room with her again.”

Mia chewed her lip.

“If you go,” she said slowly, “I don’t want you to go alone. I don’t mean physically. I mean… I don’t want you going as the scared kid they messed with. I want you going as my dad. The one who walked away to protect me.”

Robert’s eyes glistened.

“You don’t want to come?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “I’ve worked very hard to build my brain into a place where her voice isn’t allowed. I’m not inviting it back in. But if you decide to go, I’ll call you before and after. I’ll remind you who you are.”

Sometimes, children hand you more grace than you know what to do with.

A week later, Robert went to the hospital.

He asked if I wanted to come. I said yes, then no, then yes again. In the end, we decided he would go alone for the conversation, and I’d wait downstairs in the lobby with a book I wasn’t actually reading.

The oncology wing smelled like antiseptic and something sweeter underneath, like canned fruit syrup. Nurses moved quietly from room to room; TVs murmured in the background.

He paused outside Ruth’s door.

Her name was on a whiteboard with little doodles around it—flowers, stars, someone’s attempt to make the space less bleak.

He lifted his hand, knocked once, and stepped inside.

I wasn’t there for that part, obviously, but later he told me bits and pieces.

She looked smaller, he said. Not just physically, though the illness had carved her out. She looked like a woman whose certainty had finally started to crack.

“Robert,” she’d said, surprised and breathless.

“Mom,” he’d replied, standing at the foot of the bed, hands in his pockets to keep them from shaking.

“You came,” she said.

“You put my name down,” he said. “The hospital called.”

She tried to make a joke, he said. Something about how you could always count on hospitals to bring families together. It fell flat between them.

There were pleasantries. How are you, how is work, how is “the girl.”

He didn’t answer that last one.

At some point, she said, “You’ve always been so dramatic, you know. Cutting us off like that.”

And he’d said, quietly, “You told my child she wasn’t part of her own family. I think that’s the definition of dramatic.”

He didn’t go there to fight. He didn’t go for catharsis, or closure, or any of the words people put on the box of a lifetime of hurt.

He went to see if the woman who’d raised him had any interest in meeting the man he’d become.

She didn’t, not really.

She apologized a little. Not for what she’d said to Mia, but for “how things turned out.” She said she missed him. She said opportunities had passed, bridges had burned, as if it were the fault of time instead of decisions.

He listened. He didn’t argue. He didn’t open old files. When she tried to talk about “that night,” she framed it as everyone being “overly emotional” and “confused.”

That was the moment, he told me, when he felt something inside him go still.

He realized she would never see what she’d done as anything other than a misunderstanding. She could acknowledge pain in theory, but not in practice.

So he did the only thing he could.

He changed what this visit was for.

“I wish you comfort,” he told her. “I hope they’re taking good care of you.”

“That’s it?” she’d asked, annoyed. “No forgiveness? No ‘I love you, Mom’?”

“I forgave you a long time ago,” he said. “For my sake. Not yours. But I can’t put myself back in a place where you have access to my daughter. Or my peace.”

She scoffed. “Still letting that woman control you.”

He almost laughed, he said. Because there she was, on a hospital bed with tubes in her arm, and she still thought control was the point.

“I’m letting myself be a father,” he said. “That’s what you never understood.”

He left after fifteen minutes.

In the lobby, he found me pretending to read the same paragraph for the fourth time.

“Well?” I asked.

He sat down hard beside me.

“I’m glad I went,” he said. “And I’m glad I don’t have to go again.”

We drove home with the windows cracked, spring air pushing in. He called Mia from the car and told her the truth: that it had been hard and sad and weird and not at all like a movie scene where someone suddenly sees the light.

She listened. Then she said, “Thanks for trying,” and, “Thanks for coming back the same person you left as.”

Ruth passed away six months later.

We found out from cousin Sam, via a short, awkward message.

hey. just wanted you to know my aunt ruth died last night. small service next week. no pressure. just thought you should know.

We didn’t go.

We lit a candle in our living room instead. Not because she deserved a ritual, necessarily, but because we needed one.

Robert stood in front of the little votive on the coffee table, the flame flickering in the dim.

“For the good parts,” he said quietly. “And for the parts I’ll stop carrying now.”

We held a different kind of memorial, too.

We pulled out old pictures—Robert as a kid, freckles and missing teeth. Jenna in a princess costume. Family vacations where everyone looked sunburned and slightly stressed. We let Mia ask questions about the grandmother she barely knew, and we answered honestly without making her a villain or a saint.

“She was complicated,” I said. “She loved control more than she loved people, sometimes. But there were moments. She made a really good lemon pie. She taught your dad how to ride a bike. Life is weird that way.”

Mia nodded, absorbing it, older now, able to hold contradictions.

“What about Grandpa Gerald?” she asked.

“He’s still alive,” Robert said. “As far as I know.”

“Do you ever think about… I don’t know. Talking to him?” she asked.

“Sometimes,” Robert admitted. “And then I remember he’s the one who told you to your face that you weren’t really his granddaughter. And the urge goes away.”

She nodded. “Okay,” she said simply.

Being an adult is realizing that some doors stay closed not out of spite, but out of safety.

Time did its usual thing. It moved.

Mia graduated college. She got an internship, then a job, then a slightly better job. She and Eli broke up amicably, got back together briefly, then finally ended things for real with hugs and shared playlists and no hard feelings.

“So much for my perfect son-in-law,” Robert muttered.

“He’s twenty-two,” I said. “You can’t expect emotional permanence from someone who still buys furniture out of a box.”

She dated other people. She made mistakes. She called us when she needed advice and when she didn’t. We visited her in her first real apartment, a fourth-floor walk-up with questionable plumbing and a killer view.

One night, when she was twenty-six, she came over for dinner with a look on her face I recognized immediately.

“What?” I asked, before she’d even taken her shoes off.

She grinned, cheeks flushing. “Okay, don’t freak out,” she said.

“We’re already freaking out,” Robert said.

She held up her left hand.

There was a ring.

It wasn’t flashy. Simple band, small stone, the kind of ring chosen by someone who values meaning over spectacle.

“His name is Noah,” she said. “You’ve met him, Dad. The guy from book club? The one who argued with you about that documentary for like thirty minutes.”

“That guy?” Robert said. “The one who admitted he’s never seen Die Hard?”

“The one who listens when I talk,” she said. “Who asks questions. Who doesn’t get weird when I explain the whole donor situation. Who, when I told him what happened with your parents, said, ‘They don’t deserve you,’ and somehow made me feel better instead of worse.”

I felt something unclench in my chest.

“When do we get to interrogate him?” I asked lightly.

“We’re having a small engagement thing in two weeks,” she said. “Just friends. And you, obviously. I want you there when we tell people the story.”

“What story?” Robert asked.

“That the first time I realized what kind of partner I wanted,” she said, “was the night you stood in our hallway and told your parents to leave.”

Silence stretched for a second.

“Guess we did something right,” I said.

Noah turned out to be exactly what she’d described: gentle, thoughtful, with a dry sense of humor and the kind of patience that only comes from genuinely liking people. He shook Robert’s hand, hugged me, and helped carry in salad and drinks like he’d been part of the family for years.

At the engagement party, there were fairy lights in the backyard and mismatched chairs and a playlist Mia had agonized over for days. Friends from high school, college, and work mingled, eating finger foods and telling stories.

At one point, someone clinked a glass for a toast. It ended up being Mia.

“I’m not great at speeches,” she said, already lying, “but I want to say something.”

She looked at Noah, then at us.

“When I was seven,” she said, “someone tried to tell me that family is blood. That I wasn’t really part of mine. That I didn’t belong.”

The backyard got very quiet, in that way that means everyone senses they’re about to hear something important.

“And my dad,” she continued, “looked at the people saying that and said, ‘You’re not her grandparents anymore. And I’m not your son anymore.’”

She smiled at him, eyes bright.

“That was the first time I really understood what it means to be chosen. To be kept. To be fought for. So when I met this guy”—she jerked her thumb at Noah—“I knew what to look for. I knew love wasn’t about matching features or shared last names. It was about who shows up. Who stays. Who says, ‘She’s my daughter. There was never a choice.’”

Robert stared at her, stunned.

“So this is kind of your fault,” she said. “In a good way.”

There were laughs, sniffles, the soft sound of someone blowing their nose not very discreetly.

Later that night, after everyone had left and we were cleaning up paper cups and empty plates, Mia found me in the kitchen.

“Hey,” she said, leaning against the counter. “I’ve been thinking about… the grandparents conversation.”

“Okay,” I said. “About what part?”

“The part where my future kids ask why they don’t have a Grandma Ruth and Grandpa Gerald,” she said. “I want to be ready for that.”

I set down the dish I was drying.

“What do you want to tell them?” I asked.

“That they had great-grandparents who were very good at some things and very bad at others,” she said. “That they made choices that hurt people. That Mom and Dad chose not to let that hurt keep going. That sometimes love looks like letting go.”

“That sounds pretty solid to me,” I said.

“Do you still have that letter from Aunt Jenna?” she asked.

“I do,” I said. “In the file cabinet. Bottom drawer.”

“Don’t give it to me yet,” she said. “Maybe someday. Maybe when I’m ready. But it makes me feel better knowing it exists. Proof on paper that what I remember is real.”

“Your memories are real even without paper,” I said.

“I know,” she said. “But sometimes a girl likes footnotes.”

She hugged me, then went back outside to sit with Noah and Robert under the fading glow of the backyard lights.

I watched them through the window for a second: my husband with gray at his temples, my daughter with a ring on her finger, her future husband, all talking and laughing and passing around a bowl of chips.

The American flag magnet on our fridge caught my eye in the reflection. Straight, steady, holding up a list Mia had written years ago: “Family Rules—1. No lying. 2. No yelling. 3. No making people feel small.”

We’d added a fourth later: “4. Tacos are sacred.”

Years ago, in a different kitchen with a crooked magnet and a room full of people who believed DNA was the only thing that counted, I’d felt the floor fall out from under us.

Now, in our own house, with our own rules and our own chosen people, I felt the opposite.

I felt the ground under my feet, solid and real.

So, if you’re still wondering whether Robert went too far when he told his family they were done—that they were no longer grandparents, that he was no longer their son—here’s what I’ll tell you:

Every time our daughter looks at him and sees stability instead of doubt, every time she chooses partners and friends who treat her like she belongs, every time she says, “This is my family,” without flinching, I know the answer.

He didn’t go too far.

He went exactly far enough.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load