‘You’ve been getting disability payments for years.’

My grandpa said it like he was reading a headline, not detonating a bomb in the middle of Thanksgiving dinner.

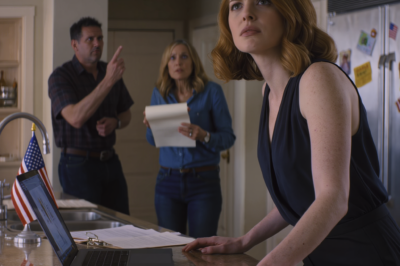

The room went still before I even looked up. A chair scraped. Somewhere down the table a fork hit a plate and clattered loud in the sudden quiet. Sinatra was crooning softly from my parents’ Bluetooth speaker in the corner, something old and smooth about love and New York, totally at odds with the way the air snapped tight around us.

On the fridge behind Grandpa, a faded American flag magnet held up Emma’s latest vacation postcard from Miami Beach. Condensation slid down a pitcher of sweet iced tea, catching the warm light from the hanging fixture. It should’ve been one of those cozy, all‑American scenes people post online with captions about family and gratitude.

Instead, my grandfather’s voice cut right through it.

‘You’ve been getting disability payments for years, Iris.’

Every face turned toward me like someone had hit a spotlight. I felt the heat rise under my skin, prickling across my shoulders and down my spine. The silence wasn’t the kind that waits for an answer. It was the kind that waits for a reaction, a crack, a confession.

My throat went dry. I managed one breath, then heard myself whisper, ‘What do you mean?’

That was when I saw him.

A man stood behind my grandfather’s chair, tall, straight‑backed, holding a closed navy folder at his side. He wasn’t family. His posture was too precise, his suit too stiff for our usual jeans‑and‑sweater gatherings. His eyes swept the table once, calmly, like he was counting witnesses.

My parents wouldn’t look at me.

Mom—Linda—stared at her cloth napkin as if the stitching had suddenly become fascinating. Dad—Mark—kept his gaze pinned on his plate, on the slice of turkey he’d been cutting, knife still resting in his hand. My younger sister Emma, sitting close to Mom like a matching accessory, frowned down at her phone as if the Wi‑Fi had gone out at the worst possible moment.

Nobody answered my question.

The man with the folder stepped a little closer to Grandpa’s chair. His movement was small, but it was enough to make my chest tighten. I didn’t know who he was yet. I just knew one thing with perfect clarity: whatever this was, it wasn’t a joke, and it wasn’t a mistake.

On the floor beside my chair, my old canvas bag leaned against the leg of the table. Inside, where it always was, sat a small spiral notebook with a bent cover, the one where I tracked every copay, every clinic fee, every bottle of generic pain meds. For years, I had believed that notebook was proof I was being responsible.

I was about to find out it was evidence of something else entirely.

That was the last second of my life where I could pretend I understood my own story.

I grew up in a house where silence traveled faster than truth. Our two‑story starter home in the Seattle suburbs had beige siding, a swing in the backyard, and a front porch with a seasonal wreath my mom changed like clockwork. From the outside, we looked perfectly average. Inside, the rules were invisible and non‑negotiable.

My parents liked things neat, predictable, controlled. Mom organized her pantry with labeled bins and color‑coded sticky notes. Dad tracked insurance premiums and utility bills on a spreadsheet we weren’t allowed to touch. The message was clear from the time I could reach the counter: as long as you didn’t create problems, you were easy to love.

Emma figured that out immediately—except for her, ‘not creating problems’ meant that if she wanted something, the world rearranged itself. She was three years younger than me but somehow always older in the room. When she walked in, conversations shifted toward her. When she asked for something, it appeared. When she struggled, someone stepped in before she even felt the fall.

‘Emma just needs a little more support,’ Dad would say, tapping his spreadsheet like it proved something.

Support was the one thing I never seemed to qualify for.

I remember the first time I felt the imbalance settle into my bones. I was twelve, standing barefoot in the kitchen with a crumpled field trip form in my hand. Our class was going to the science museum. The fee was thirty‑five dollars. I’d already filled in my name carefully, block letters pressed into the cheap paper.

Mom was at the counter with a stack of bills and envelopes spread around her like a paper moat. She didn’t look up when I cleared my throat.

‘Can you sign this?’ I asked. ‘It’s due Friday.’

She took the paper, glanced once at the amount, and sighed. ‘We can’t do extras this month, Iris. Things are tight.’ She slid the form back toward me without meeting my eyes.

I nodded, because arguing never changed the outcome. I folded the paper smaller, pressing the crease with my thumb, telling myself the museum probably wasn’t that exciting anyway.

Five minutes later, the front door flew open and Emma burst in, cheeks flushed from the cold, waving a glossy flyer like a flag.

‘Mom! They’re starting a new dance class at the studio. Hip‑hop! Look, they said I’d be perfect.’ She shoved the flyer into Mom’s hands, talking so fast the words tumbled over each other.

Mom’s face softened immediately. ‘Oh, that sounds fun.’ She scanned the flyer, eyes pausing on the price I knew was higher than my field trip. ‘Of course, sweetheart. We’ll make it work.’

Same week, same stack of bills on the counter, different rules.

A hinge cracked quietly inside me that day.

By high school, the pattern didn’t break; it deepened. When Emma’s laptop screen cracked two weeks before finals, Dad had a replacement shipped overnight from an electronics store, grumbling about expedited shipping but entering his credit card number anyway.

When my laptop died my junior year, he barely looked up from his email.

‘Use the computers at the library,’ he said. ‘You don’t need your own device to write an essay. People used typewriters for decades.’

Emma got private tutors when she struggled with calculus. I got a reminder to ‘work harder’ and a printed list of free online resources our slow internet could barely load.

That was how our house worked: two kids, two realities, one truth nobody said out loud—only one of us was considered an investment.

Then came the injury.

I was nineteen, working a part‑time evening shift at a big‑box store off the highway to help cover community college. The store smelled like rubber and floor cleaner, bright lights buzzing overhead, carts squeaking across wide aisles. I was in the back, helping unload a pallet of boxed fans. Someone had just mopped, but no one put out a sign.

My sneaker hit the wet tile and slid. For a half‑second, I was weightless, arms pinwheeling, cardboard blurring around me. Then my back slammed into the floor, and it felt like someone had jammed a live wire straight into my spine.

The manager hovered over me, face pale, radio crackling at his shoulder.

‘Can you stand?’ he asked.

‘I… think so.’ I lied, because I needed the job and because I’d been raised to believe that pain was an inconvenience, not information.

They offered to call 911. I said no. The thought of an ambulance bill made my stomach clench harder than the injury did.

I went home with a bruise blooming under my skin and a bottle of over‑the‑counter pain relievers in my bag. I told myself it would fade.

It never really did.

In the months that followed, I moved slower. I learned to bend with my knees, to lift carefully, to hide the way my face tightened whenever I carried more than one heavy box. I started seeing a sliding‑scale clinic when I could afford it. They gave me muscle relaxers and physical therapy exercises printed on thin paper.

The first time a doctor wrote ‘chronic back pain’ on my chart, I stared at the word ‘chronic’ until it blurred. It sounded official, permanent, like it deserved its own line in Dad’s spreadsheet.

I showed Mom the prescription once, thinking she’d worry, that she’d at least pretend to.

She was in the kitchen, of course. New stainless steel appliances gleamed under recessed lighting they’d installed that spring. The fridge—sleek, double‑doored, with a touch screen—was spotless except for the flag magnet holding up Emma’s postcard.

‘Can you help me cover this?’ I asked, placing the crumpled prescription slip on the counter next to a little orange bottle with only two pills left. My voice came out small even to my own ears.

Mom didn’t turn around. She kept seasoning chicken breasts, the click of the pepper grinder steady.

‘You need to be tougher, Iris,’ she said. ‘Don’t be dramatic. Don’t depend on anyone. You’re stronger than that.’

The words landed heavy, layering over every lesson I’d learned without anyone saying it outright: needing help was weakness, and weakness was expensive.

Beside her, the kitchen glowed like a showroom. Brand‑new appliances. Quartz countertops. A backsplash she’d picked from a home improvement catalog. All the money, all the planning, all the care—none of it had ever been aimed at me.

I stood there under the dimmer over the sink, holding a bottle that rattled empty, and understood something I hadn’t wanted to see: effort didn’t matter, pain didn’t matter, need didn’t matter.

Only the hierarchy did.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t argue. I just nodded, slid the bottle back into my bag, and folded the prescription slip into my small spiral notebook. That was the night I realized exactly where I fit in this family.

Back at the dinner table in the present, the room felt smaller than I remembered. Same house, same soft overhead lighting, same long table my parents brought out for every holiday. But nothing about the scene felt warm.

Linda and Mark sat at the center, angled like anchors toward the relatives they wanted to impress—Aunt Carol with her perfect manicure, Uncle Joe in his Seahawks pullover. Emma, in a pale sweater that probably cost more than my monthly bus pass, leaned close to Mom, whispering something that made them both smile.

I watched the curve of their shoulders, the easy rise and fall of their breathing. It was the kind of comfort I had never been invited into.

At the far end, Grandpa watched me.

He was the only person in the room who wasn’t pretending this night was normal. His jaw was tight, his eyes tracing the shape of my face like he was looking for something—confirmation, maybe, or a truth he hoped wasn’t true.

The man with the navy folder hadn’t been introduced. But even before I knew his name, I could read his presence: official, deliberate, the human equivalent of a signature line at the bottom of a form.

Dinner had clattered along up until the moment Grandpa spoke. Small talk. Compliments about the turkey. Emma talking loudly about her next vacation—Cancún this time—while my parents nodded like they’d personally curated her life.

I kept my hands in my lap, fingers laced together to stop them from shaking. My canvas bag rested against my ankle, the faint weight of the notebook inside grounding and mocking at the same time.

Grandpa didn’t touch his fork. He waited.

Then he said it again.

‘You’ve been getting disability payments for years.’

This time, he didn’t raise his voice. He spoke calmly, almost gently, like he wanted the words to land one by one, undeniable.

The table quieted. A cousin glanced at me, confused. Emma looked annoyed, like the interruption inconvenienced her.

Something heavy sank inside me. Not fear, not anger. Something slower, more dangerous—a dawning awareness that everyone here might know more about my life than I did.

I swallowed. ‘What do you mean?’ I asked again, a little louder.

Mom’s fingers froze around her napkin. Dad’s jaw clenched. Nobody answered.

The man with the folder took one measured step forward.

I felt the hinge of the night shift.

For a heartbeat, I imagined making a scene. Slamming my hands on the table, demanding answers, forcing everyone’s eyes to stay on me. But I’d spent my entire life being told I was ‘too sensitive’ whenever I objected to anything. I knew how it would go: my questions would be labeled drama, my confusion recast as ingratitude.

So I did the most disarming thing I could.

‘I need a minute,’ I said quietly.

I pushed my chair back. The legs scraped against the hardwood. No one tried to stop me. No one called my name. No one said, ‘Wait, this is a misunderstanding, we’ll explain.’

The conversation behind me didn’t even fully die. It just shrank, hushed, then slowly restarted around the absence of my chair.

That was the strange part—how easy it was for them to watch me walk away from an accusation that should have rocked the entire table.

The hallway outside the dining room was narrow and dim, lined with framed photos in mismatched black frames. Near the doorway, a picture I’d seen a hundred times caught the glow of a small lamp: my parents and Emma at the Grand Canyon a few summers back. Dad in sunglasses, Mom in a floppy hat, Emma in high‑waisted shorts, all three smiling into the Arizona sun.

I wasn’t in the picture. I’d been stocking shelves that weekend, back screaming, watching other people’s vacation photos scroll by on my phone during my five‑minute breaks.

I stood there for a moment, studying that gap where I should have been. My heart wasn’t racing. It was moving slow and steady, like it had finally given up being startled by this family.

I tightened my grip on the strap of my canvas bag and slipped into the small bathroom across the hall.

The mirror over the sink reflected the fuzziness of the overhead bulb. I pressed two fingers to the bridge of my nose, my usual reflex when something heavier than anger settled in my chest.

My reflection looked calm, too calm. Like someone waiting for instructions.

I sat on the closed toilet lid, pulled my spiral notebook from the bag, and set it on my knees. Every page was crowded with dates and numbers, cheap ink bleeding into cheap paper. Rent. Medication. Groceries. Bus fare. Clinic fees. Copays.

I ran my thumb along the frayed edge of one page, remembering nights I’d sat at my tiny kitchen table in my Seattle apartment, calculating whether skipping one meal could stretch my prescriptions one more week.

I had always told myself the math was temporary.

If disability payments had been coming in for ‘years’ the way Grandpa said… then someone else had been doing math with money that should have been mine.

I pulled out my phone. No missed calls. No texts from my parents asking where I’d gone. Nothing but a group chat about football and a promotional email from the grocery delivery app I couldn’t afford.

I opened my banking app. My balance blinked back at me, small and honest. I scrolled through deposit after deposit—paychecks, tax refunds, one stimulus payment from a year the government remembered people like me existed. No mysterious extra deposits. No steady stream of support from a program I hadn’t even known I qualified for.

Cold clarity slid into place.

I opened my email and drafted a message to the Social Security Administration office, fingers moving without hesitation.

Hello,

I’m writing to request a full history of any disability payments issued under my name over the past ten years. Please also confirm all addresses and bank accounts on file.

Thank you,

Iris Taylor

No dramatics. No backstory. Just a question that should have belonged to me the first time a doctor wrote ‘chronic’ next to my name.

When I hit send, the calm in my reflection finally made sense.

I wasn’t going to yell in that dining room. I wasn’t going to beg my parents for information about my own life.

I was going to build my own record.

When I walked back toward the dining room, I didn’t go all the way in. I stood just inside the doorway, watching. Grandpa still sat at the far end, arms crossed, eyes sharp. The man with the navy folder—who I would later learn was an auditor named Daniel Stevens—remained standing, the folder still closed.

My parents were laughing at something Aunt Carol had said. Emma was scrolling, back in her safe glow.

The life at that table hadn’t even paused.

For a second, I imagined dropping my notebook onto the table, flipping it open to all the tiny numbers documenting how much of my life had gone uncovered. But confrontation was their language. Silence had always been my currency of survival.

So I picked up my coat from the back of my abandoned chair and slipped it on.

Grandpa saw me. His eyes softened for a heartbeat, but he didn’t call out. He didn’t need to.

He already knew I wasn’t leaving in fear.

I was leaving to build something.

Outside, the November air was cold and thin, sharp enough to scrape the inside of my throat. The neighborhood looked like a commercial for middle‑class stability: trimmed lawns, flagpoles in front yards, porch lights glowing warm.

I walked to the end of the driveway, the gravel crunching under my boots. Under a streetlight humming faintly above me, I pulled my receipts from the notebook—small stacks of thin, crumpled paper documenting clinic visits, generic meds, emergency room copays from nights I couldn’t breathe through the spasms.

Years of survival.

Not one cent of it supplemented by the disability money I was apparently ‘getting.’

I held the papers tighter when the wind tried to lift them.

When I finally made it back to my apartment in Seattle, the hallway light on my floor flickered the way it always did, buzzing, dimming, then throwing harsh brightness for a second. The landlord kept saying an electrician would fix it ‘soon.’ I’d stopped believing that months ago.

Tonight, I didn’t turn it off. I let it flicker while I unlocked my door.

Inside, my studio was small but mine. A thrift‑store couch, a scarred coffee table, a secondhand bookshelf with a leaning stack of library books. The hum of the refrigerator filled the silence.

I dropped my keys in the little ceramic bowl by the door and spread everything out on the floor—receipts, medical bills, letters from clinics, my spiral notebook, my pay stubs.

I sat cross‑legged in the middle of it all and let the quiet settle. No Sinatra. No overlapping family conversations. Just the sound of my own breathing and the fridge kicking on every so often.

Then I went to work.

I opened my battered laptop and created a spreadsheet. In one column, I entered dates. In the next, descriptions—’clinic copay,’ ‘ER visit,’ ‘physical therapy,’ ‘prescription refill.’ In another, the amounts I’d paid. I added a new column for ‘Estimated Disability Support.’

I googled the ballpark monthly payments people with my kind of condition and work history might receive. The range made my stomach twist, not because it was huge, but because even the low end would have changed everything.

I picked a conservative number and started multiplying by months.

Ten years. One hundred and twenty payments.

When the total in the ‘Estimated Disability Support’ column passed $280,000, I didn’t feel anger or shock.

I felt the weight of truth settling into place, cell by cell.

Hour by hour, the spreadsheet grew. As the numbers stacked up, a picture emerged, clearer than any family portrait on my parents’ walls: a life lived on razor‑thin margins while someone else cashed in on the safety net that had been meant for me.

Around midnight, my email chimed.

The Social Security office had acknowledged my request. They would begin reviewing my file and respond with a full payment history and associated addresses.

I stared at the message for a long beat, then at the papers scattered around me, then at the spiral notebook still open on the floor.

I exhaled slowly.

‘I won’t fix what they’ve broken,’ I whispered into the empty room.

The fridge hummed in response, steady and indifferent.

The next morning, the November sky hung low and gray over my parents’ street. When Grandpa’s old Ford pulled up in front of my building right on time, I was already waiting on the sidewalk with my canvas bag over my shoulder and the notebook tucked safely inside.

He didn’t say ‘good morning’ when I climbed in. He didn’t ask if I was sure.

‘You don’t have to go back there,’ he said instead.

‘I know.’ I buckled my seat belt. ‘I want to.’

He nodded once and pulled away from the curb.

We drove mostly in silence. He kept both hands on the wheel, knuckles pale but steady. The city slid by—coffee shops with chalkboard signs, people walking dogs in raincoats, a bus stop with a woman clutching a brown paper bag.

‘When did you find out?’ I asked finally, watching the wet streets blur under the wipers.

‘A week ago,’ he said. ‘I was helping your mother with some paperwork she didn’t understand. Her words, not mine. I saw a line item on a bank statement that didn’t make sense.’ His jaw tightened. ‘I asked questions. They got defensive. So I hired Stevens.’

‘You hired an auditor,’ I repeated.

‘I hired someone who knows how to read numbers people don’t want read.’

I let that sit for a minute.

‘Why?’ I asked. It wasn’t really about the auditor. It was about everything.

Grandpa’s eyes stayed on the road. ‘You’ve always told the truth, Iris. Even when it cost you. I couldn’t stand the thought that someone was using your name to lie.’

Something in my chest loosened and hurt at the same time.

When we turned onto my parents’ street, the driveway and curb were already full. Cars lined up bumper to bumper, like someone was hosting a celebration instead of waiting for a truth to detonate.

I stood on the sidewalk for a moment after I got out, letting the cold air settle over my face. My breath rose in thin white strands before disappearing. It felt fitting.

Inside, the dining room looked exactly the same as the night before. Same long table. Same warm light. Same chairs. Same placement: my parents in the middle, Emma at Mom’s side, Grandpa at the far end.

But there was one difference.

Today, the man with the navy folder stood at Grandpa’s shoulder instead of behind him.

No one greeted me. That wasn’t unusual. I slipped into the room and took up a spot near the wall instead of at my old seat. Stevens glanced at me and gave a small, professional nod. Grandpa’s jaw tightened for a second, then relaxed.

‘This won’t take long,’ Grandpa said, his voice steady, stripped of its usual warmth. It wasn’t anger. It was authority I hadn’t seen him use in years.

Mom shifted in her chair. ‘Dad, can we not do this right now? Iris is clearly overwhelmed. She—’

Grandpa raised one hand. She went quiet.

‘This isn’t about Iris,’ he said. ‘This is about what was taken from her.’

Dad cleared his throat, trying to sound calm. ‘We didn’t take anything. There’s been a misunderstanding.’

Stevens opened the folder.

The sound of paper sliding against paper cut cleaner than any accusation.

Inside were neatly stacked documents, arranged by year—ten years’ worth of statements, forms, and official letters. The Social Security logo was visible on the corner of every page.

He placed the first sheet in the center of the table. A list of monthly payments, each entry with my name, my Social Security number, and an address.

My parents’ address.

He placed another sheet. Another year. Same pattern. Same deposits. Same routing number.

On the third sheet, he tapped a line with the end of his pen.

‘These disability payments were issued to support Ms. Taylor’s medical condition,’ Stevens said. His tone was calm, clinical. ‘Every deposit was routed to this household instead of to Ms. Taylor’s residence.’

The words ‘this household’ hung in the air like a bad smell.

Mom’s face drained of color. Emma stopped scrolling mid‑swipe. Dad leaned back, arms crossing defensively over his chest like that could deflect the paperwork on the table.

‘We used that money for the family,’ Dad muttered. ‘For bills, for things the girls needed.’

Stevens stayed focused on the page. ‘For vacations?’ he asked quietly. ‘For the kitchen remodel five years ago? For the SUV purchased in cash the same year Emma started at St. Augustine Academy?’ He turned another page, his finger landing on a highlighted cash withdrawal.

Mom blinked rapidly. ‘We had expenses,’ she said. ‘School isn’t cheap. We… we thought it made sense. She’s always been so independent.’

The room pressed in on itself.

I didn’t speak. I didn’t need to. Every number on those pages was speaking for me louder than I’d ever been allowed to.

Stevens placed the final sheet on the table—a summary. Ten years. One hundred and twenty monthly deposits. The total sat at the bottom, neat and merciless.

$282,960.

I watched my parents’ faces shift. First denial, then calculation, then something hollow and brittle. The look people get when the story they’ve crafted no longer belongs to them.

Grandpa pushed his chair back. The sound echoed off the walls.

He pointed at Linda and Mark. ‘Anything to say?’ he asked.

This time, the question didn’t roar. It landed cold and flat, like a verdict that had already been decided.

Mom’s voice cracked. ‘We thought she didn’t need it. She’s always prided herself on doing everything alone. We told everyone she refused help—’

‘You told everyone she was irresponsible,’ Grandpa cut in, eyes sharp. ‘You let her go without medication. You let her work through pain so you could upgrade your kitchen.’

Dad looked at me then, really looked, like maybe for the first time he was seeing the person his decisions had been built on.

‘We were going to tell you eventually,’ he said weakly. ‘When things settled down. When—’

‘When?’ Grandpa snapped. ‘After another ten years? After the government charged you with fraud and your daughter was the one cleaning up the mess?’

Silence flooded the room. Not the quiet of awkward dinner pauses or polite disagreement. A heavier kind of silence, the kind you get in courtrooms and hospital waiting rooms.

Stevens cleared his throat softly. ‘The accounts linked to these deposits will be frozen pending investigation,’ he said. ‘Ms. Taylor will be contacted directly regarding restitution and any future payments. I advise you both to cooperate fully with the federal agents who will be following up.’

Mom’s breath hitched—a small, sharp sound. Dad’s shoulders sagged like something had finally been cut loose inside him.

Emma’s voice came out small. ‘So… what does this mean?’ she asked.

Nobody answered her.

Grandpa turned to me. His expression softened at the edges.

‘You don’t have to stay here,’ he said quietly. ‘You don’t owe them anything.’

He was wrong, but not in the way he thought.

I didn’t owe them forgiveness, or understanding, or a chance to explain how they’d justified turning my diagnosis into their side income.

I owed myself the truth. I owed myself distance.

I nodded once—not to him, but to myself.

I picked up my coat from the back of the same chair I’d left empty the night before. The fabric felt cool and familiar under my fingers. I slid my arms into the sleeves, adjusted the collar, and reached for my canvas bag. I felt the weight of the spiral notebook inside, heavier now that I knew exactly how much it had been missing.

No goodbye. No final speech. Just the soft scrape of my boots across the hardwood as I walked out.

Behind me, the silence finally broke. Not in a storm of shouting, but in the low, panicked hum of people realizing the truth had already chosen its side.

In the driveway, the air hit colder than before. Grandpa’s truck was parked at the curb. He climbed in behind the wheel without a word and waited for me to join him.

We drove in silence for a while. Streetlights carved the road into long, pale stretches. The shadows of bare branches flicked across the dashboard.

He didn’t ask if I was okay. He didn’t fill the quiet with apologies or outrage.

‘They won’t touch another dollar,’ he said finally, eyes on the road. ‘Not one.’

His voice wasn’t angry. It was final.

I nodded, fingers brushing the worn strap of my bag. Inside, Stevens’s copies of the documents he’d handed me before we left lay alongside my notebook—my name printed where it belonged, my address missing from every line.

Proof of how easy it had been to erase me on paper while still using my existence to cash checks.

When we pulled up in front of my building, Grandpa put the truck in park but didn’t turn off the engine.

‘I’m sorry I didn’t see it sooner,’ he said.

I looked at him. His face was lined and tired, but his eyes were clear.

‘You saw it,’ I said. ‘That’s enough.’

He nodded, accepting that answer instead of arguing. That alone set him apart from everyone else.

Inside my apartment, I set the folder on the kitchen counter. The papers fanned slightly at the edges, catching the morning light that slipped through the blinds. I could smell coffee from the neighbor next door, hear distant traffic, feel the solid floor under my feet.

I thought of the kitchen I’d grown up in—the gleaming appliances, the bright lights, the empty orange pill bottle hidden in my bag.

I stood there breathing slow, letting the memory pass through without slicing me open.

The spiral notebook sat next to the folder. I opened it to a fresh page.

On the top line, in my neatest handwriting, I wrote: ‘Things That Belong To Me.’

Underneath, I made a short list.

My diagnosis.

My story.

My future.

And, finally: ‘The boundaries I choose.’

Boundaries aren’t loud. They don’t always show up in courtroom speeches or dramatic confrontations. Most of the time, they’re quiet lines drawn in ordinary air.

They’re the moment you stop answering calls that only come when someone needs something. The day you take your name off a joint account you never agreed to. The night you block a number so you can fall asleep without bracing for the next blow.

They’re the simple, stubborn act of believing your life belongs to you more than to anyone else’s expectations.

Weeks later, when the official letter from Social Security arrived, it confirmed everything Stevens had laid out. Ten years of payments. My parents’ address on every account. A notation about an ongoing fraud investigation.

There was a line about restitution. There was a paragraph about my rights. There was a number to call if I had questions.

I read it once, carefully, then slid it into a plastic sleeve in the same binder where I’d placed Stevens’s documents.

I didn’t call my parents.

Word spread on its own, the way it always does in families that love gossip more than accountability. An aunt texted me a screenshot of a group chat where Mom complained about being ‘attacked’ in her own home. A cousin DM’d me on Instagram asking if I was ‘really going to press charges.’

‘It’s not up to me,’ I replied. ‘It’s up to the government.’

I didn’t add that the only thing I wanted them held responsible for was the story they’d told about me—that I was lazy, that I refused help, that I was the architect of my own struggle.

I got a new primary care doctor. I updated my address on every official form. I met once with a legal aid attorney who walked me through what might happen next: interviews, maybe a hearing, maybe their lawyer reaching out with offers that sounded generous on the surface but mostly protected my parents.

‘You don’t have to decide everything now,’ she said gently. ‘You just have to keep telling the truth.’

At my job—now an office position that still required too much sitting in bad chairs—I told my supervisor I might have to miss some hours for appointments.

‘Family stuff?’ she asked.

‘Legal stuff,’ I said.

She didn’t push for details. She just nodded and slid a box of ergonomic cushions toward me.

The first time I sat on one, my back didn’t magically stop hurting. But it hurt less. That felt like a miracle I’d actually earned.

Emma texted once, weeks after the confrontation.

I saw what happened in the group chat, she wrote. Mom’s really upset. Dad too. They say you’re letting Grandpa ruin the family.

I stared at the message for a long time before answering.

‘I didn’t cash those checks,’ I typed. ‘I won’t lie to cover for the people who did.’

She typed and erased three times before sending: You’ve always made everything so dramatic, Iris.

Once, that would’ve sent me into a spiral of self‑doubt.

This time, I put my phone face‑down on the table and picked up my notebook instead.

Under ‘Things That Belong To Me,’ I added one more line.

‘How I respond to people who refuse to see me.’

I closed the cover and let my hand rest on it, feeling the faint indent of my own handwriting.

If you’ve ever stepped away from a version of yourself that someone else created for their convenience, you know the strange mixture of grief and relief that follows. You mourn the family you thought you had, the parents you deserved, the years you can’t get back. You grieve the help you should’ve received, the nights you didn’t have to white‑knuckle your way through.

But beneath that, if you’re very quiet, there’s another feeling.

It’s small at first. A tiny, steady thing.

It’s the sound of your own voice, finally unmuted.

One night, months after the confrontation, I passed by my parents’ house on the bus. The kitchen window was lit. From my seat, I could see the outline of the stainless‑steel fridge, the glint of the stove. The flag magnet was still there, holding up something new.

I didn’t look long enough to see what.

The bus rolled on. The city shifted around me—neon signs, traffic lights, pedestrians bundled in jackets. I felt the familiar ache in my back, the familiar hum of the engine under my feet.

I reached into my bag, felt for the spiral notebook, and smiled when my fingers found it.

It was still cheap. The cover was still bent. The pages were still filled with cramped handwriting and numbers.

But now, it wasn’t just a record of what I’d survived without.

It was proof of what I’d built anyway.

You’re allowed to choose the truth that belongs to you. You’re allowed to walk away from the table where your name is only useful on a check. You’re allowed to draw a line, however quietly, and step over it.

You’re allowed to keep walking toward a life that finally fits.

Page by page, dollar by dollar, boundary by boundary, I was writing mine.

I used to think stories ended when the truth came out.

Expose the lie, watch the fallout, walk away. Roll credits.

For a while, I let myself believe that night at my parents’ table—the folder, the numbers, Grandpa’s question hanging in the air—was the climax. That everything after would just be a slow fade into normal life. A new normal, sure, but something steady.

Then the first letter from a federal agent showed up in my mailbox, and I realized I’d only finished the first chapter.

The envelope was larger than usual, the kind that makes your stomach drop before you even flip it over. My name was typed neatly in the center, the return address stamped with a federal seal. I stood there in my tiny kitchen, keys still in one hand, the spiral notebook on the counter beside me, and stared at it like it might make a sound if I waited long enough.

It didn’t.

I slid a butter knife under the flap and eased it open.

Inside was a formal letter—black ink, dense paragraphs, dates and codes—and a notice: I was being contacted as a potential victim in an ongoing fraud investigation. They referenced the disability benefits, the years, the total. $282,960. Seeing the number printed on official letterhead made my vision tunnel for a second.

The letter included a date and time for an interview, a list of documents to bring, and a reminder that I had the right to legal representation.

I set the letter down next to my spiral notebook. One looked official, stamped and scanned and certified. The other was cheap, smudged, the ink on some pages blurred from the time I fell asleep on it after a pain flare.

Both were my life in numbers.

The night before the interview, I pulled everything out again—Stevens’s copies, my spreadsheet, the letter from Social Security, my notebook. I lined them up on the table like exhibits.

For years, I’d been told I was “too sensitive” whenever I pointed out something that hurt. Now sensitivity was literally evidence. Every receipt I’d saved, every line I’d written down because I was afraid I’d forget it later—it all built a record my parents hadn’t counted on.

I clicked my pen once, twice, then forced myself to stop.

“You tell the truth,” I reminded myself out loud. “That’s it.”

The agent who interviewed me the next day didn’t look like the TV versions. No sunglasses, no dramatic suit. She wore a navy blazer over a gray sweater and had laugh lines around her eyes that didn’t disappear when her expression turned serious.

Her name was Agent Lopez.

We sat in a bland conference room downtown, the kind with beige walls and a table that had seen too many meetings. A digital recorder sat between us, its little red light blinking steadily.

“I’m going to ask you some questions about your medical history, your living situation, and your relationship with your parents,” she said. “If you need a break at any time, tell me. If you don’t remember something exactly, it’s okay to say that. We’re interested in what you experienced, not in catching you in a mistake.”

Nobody in my family had ever said anything like that to me.

For the first few questions, my voice came out thin. I told her about the injury at the store, about the clinic visits, about the prescriptions. I described my studio apartment, my jobs, the way I’d juggled classes and work and pain.

“Did anyone ever tell you you were approved for disability benefits?” she asked.

“No.”

“Did anyone in your family suggest applying?”

“No.”

“Did you ever sign any forms authorizing your parents to receive payments on your behalf?”

“No.” The word came out sharper that time.

Her gaze flicked up from her notes, meeting mine. “Did you ever know that payments were being issued at all?”

“Only when my grandfather confronted them,” I said. “At Thanksgiving.”

Her eyebrows rose a fraction. “That’s when you found out about ten years of benefits? At a holiday dinner?”

“Yes.”

She let out a low breath through her nose, the bureaucratic version of a curse.

The questions went on. Had my parents ever discussed finances with me? Had they ever paid my rent? Covered my prescriptions? Helped with hospital bills? Did I have emails, texts, voicemails where they mentioned helping—or not helping?

I thought of the time I’d texted my mom from the ER, hand shaking, saying, They think it might be a disc, I’m scared.

She’d replied hours later with, Keep me posted. Busy right now.

“I have some messages,” I said. “They’re not about money directly. But they’re… context.”

“Context matters,” Lopez said. “We’ll take whatever you’re comfortable sharing.”

When the interview ended, my throat felt raw, like I’d swallowed sand. Agent Lopez slid her card across the table.

“You did well,” she said.

“I just told the truth,” I replied.

“That’s harder than you’d think,” she said. “Especially when family is involved.”

On my way home, I stopped at a coffee shop near my bus stop and ordered the cheapest thing on the menu just to justify sitting there. I opened my spiral notebook and wrote down everything I could remember from the interview while it was still fresh.

The guy at the table next to me had his earbuds in, nodding along to something with a beat. A couple in the corner argued quietly about a vacation rental. A kid near the window was coloring an American flag in a workbook, red and blue crayons pressed hard into the paper.

Normal life hummed all around me.

I underlined the number again: $282,960.

It still didn’t feel real. That amount, stretched over ten years, wasn’t enough to make anyone rich. But it was enough to mean I didn’t have to choose between heating and medication some winters. Enough to mean maybe I could’ve had a slightly bigger apartment, or a car that didn’t sound like it was begging for mercy every time it climbed a hill.

Enough to mean I wouldn’t have spent so many nights wondering if I was just bad at being an adult.

Every few days after that, something new would arrive—another letter, another email, another call I let go to voicemail so I could listen when I was ready. Sometimes it was the attorney from legal aid checking in. Sometimes it was someone from Social Security asking for one more form, one more signature.

Sometimes it was my parents.

They started slow. A text from Mom: We need to talk. A missed call from Dad. A voicemail from an unknown number that turned out to be Emma using a friend’s phone.

I didn’t answer.

Once, Emma left a voice message that went on for almost three minutes. I listened to it on a Sunday morning while making pancakes, phone propped against the salt shaker.

“Iris, this is insane,” she said. Her voice wobbled at the edges, shaky but still edged with the familiar frustration she always used on me. “Mom is sick over this. Dad can’t sleep. They said Grandpa is exaggerating everything. You know how he gets. They could go to jail. Do you want that? Over some money you didn’t even know about?”

I flipped a pancake and watched the batter bubble.

“You’ve always made things so difficult,” she continued. “You could fix this if you wanted. Just tell them you’re not pressing charges. Tell the government it was a misunderstanding. You’re good at telling stories, right? Use that.”

Pancake, bubbles, flip.

“You’re ruining the family,” she finished quietly. “For what?”

For what.

I set the spatula down and leaned on the counter, listening to the last few seconds of empty line before the message ended.

I wanted to call her back and tell her that I was not pressing charges; that wasn’t how this worked. I wanted to explain that fraud against the government wasn’t something you could wave away with a nice apology and a promise to do better.

But mostly, I wanted to ask her if she’d ever once, in ten years, wondered how I kept a roof over my head when I was missing work for medical appointments. If she’d ever thought about the fact that our parents could hand her a credit card for a spring break trip to Cabo but couldn’t spot me fifty bucks for medication without acting like I was draining their retirement.

Instead, I picked up my spiral notebook, flipped to the “Things That Belong To Me” page, and added another line.

“The guilt I refuse to carry for other people’s choices.”

One afternoon, Grandpa called.

“They came by,” he said without preamble.

“Who?” I asked, even though I already knew.

“Your parents. They wanted me to talk to you,” he said. I could hear the clink of his mug as he set it down. “They said you’re overreacting. That you’re letting the government tear us apart.”

“What did you say?” I asked.

“I told them they tore this family apart when they started cashing checks in your name,” he replied. “Then I told them to leave.” He paused. “They’re scared, Iris. People do ugly, desperate things when they’re scared.”

“I know,” I said. “I grew up with them, remember?”

He made a sound that might’ve been a laugh if it didn’t catch halfway.

“You’re not responsible for saving them,” he said.

The thing about being the “independent” one in the family is that people start to believe you’re a resource, not a person. The one who can bail everyone out. The one who can swallow their own feelings to keep the peace.

For the first time, I started to believe I could opt out of that role.

The investigation stretched on—government wheels turning slowly, gathering documents, interviewing people. There were days when nothing happened and days when everything happened at once. A notice about restitution. A call from an investigator asking if I’d be willing to testify if it came to that. An email from legal aid explaining terms I’d only ever heard on TV.

“They might offer a plea deal,” the attorney said over Zoom one evening. “If that happens, you won’t have to testify. But they may ask for a victim impact statement from you.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“Basically, you write down how this affected you,” she said. “Financially, emotionally, physically. It helps the court understand that this isn’t just numbers. It’s your life.”

I looked at the stack of papers on my table. The flag magnet flashed in my memory, holding up Emma’s postcards. The empty pill bottle in my bag. The spreadsheet. The notebook.

“I can do that,” I said.

The night I started writing it, I made tea and then forgot to drink it. The mug cooled on the table beside me while I stared at a blank document on my laptop. The cursor blinked accusingly.

Victim impact statement.

I’d spent my whole life avoiding the word “victim.” I didn’t want anyone’s pity. I didn’t want to be reduced to the worst things that had happened to me. I’d survived too much to let a label do all the talking.

But this wasn’t about who I was.

It was about what had been done.

So I started typing.

I wrote about the time I skipped a follow‑up appointment because I couldn’t afford both the visit and my share of the electric bill. I wrote about the winter I slept in two pairs of socks and a hoodie because I kept the heat at sixty‑two degrees. I wrote about the nights my back hurt so badly I couldn’t stand up straight, but I went to work anyway because missing one more shift might get me fired.

I wrote about the way my parents talked about me at family gatherings—how they rolled their eyes and told people I “refused help,” that I was “too proud” to accept money, that I “liked to struggle.” I wrote about the humiliation of realizing they’d been saying that while cashing checks with my name on them.

I wrote about the number. $282,960. How seeing it made me re‑evaluate a decade of choices I’d thought were mine. How it felt like looking at an alternate life I never got to live.

By the time I finished, my tea was cold and my chest felt strangely light.

I printed the statement and slid it into a folder with everything else. My life, condensed into paper and ink.

Weeks later, my attorney called.

“They took a deal,” she said. “Your parents.” She didn’t have to specify.

I sat down slowly. “What does that mean?”

“They pled guilty to misusing disability benefits and making false statements,” she said. “There won’t be a trial. They’ve agreed to a restitution plan and a period of supervised release. The court took your statement into account when determining the terms.” She paused. “They’ll have to start paying back what they took.”

“To me?” I asked.

“To the government,” she said. “But Social Security will also be issuing back payments directly to you going forward. Not the full amount—they won’t double pay—but a portion. And your monthly benefits will be routed to your account from now on.” She hesitated. “How are you feeling about that?”

I looked around my apartment. Same couch. Same wobbly table. Same flickering hallway light outside.

“Like someone adjusted the volume on my life,” I said. “The noise is still there. But it’s… different.”

That month, when my first direct disability payment landed in my account, I stared at the screen for a full minute before I believed it. The number wasn’t huge. It wouldn’t make me rich. It wouldn’t erase a decade of strain.

But it was honest.

My name. My account.

My life, finally acknowledged on paper.

I printed the confirmation and taped it to the inside cover of my spiral notebook.

The calls from my parents didn’t stop after the plea deal. If anything, they increased. Sometimes they were furious—blaming me for the consequences of their choices. Sometimes they were pleading—begging me to “help explain” to friends and extended family that it wasn’t “as bad as it sounded.”

I stopped listening to the voicemails.

One day, a letter arrived from my mother. The envelope was thick, her handwriting looping across the front the way it had on permission slips and Christmas cards.

I turned it over in my hands a few times before opening it.

Inside were three pages of blue ink. No apology in the first paragraph. No acceptance of responsibility. Just a long explanation of stress and sacrifice and how hard she and Dad had worked to “keep the family afloat.”

Somewhere in the second page, she wrote, We always thought you were fine. You never asked for anything.

I set the letter on the table and stared at that sentence until the words blurred.

You never asked for anything.

I thought of the field trip form. The prescriptions. The ER text. The times I’d stood in that gleaming kitchen and swallowed the urge to say, I need help, because I already knew the answer.

I picked up a pen and underlined the sentence.

Then, on a separate piece of paper, I wrote: I shouldn’t have had to.

I folded her letter back up, slid it into the envelope, and put it in a shoebox on my closet shelf. Not to keep as some sentimental artifact, but as a reminder—a physical record of the story she would always tell herself.

It wasn’t my job to edit it anymore.

In the middle of all of this, life still happened.

I went to physical therapy and learned new stretches that made my back ache less. I started seeing a therapist at a community clinic, sitting in a small room with a fake plant and a box of tissues, talking about things I’d spent years pretending didn’t hurt.

“You were taught that needing help was dangerous,” she said once. “That’s a hard lesson to unlearn.”

“I was taught that needing help was expensive,” I corrected softly.

She tilted her head. “And now?”

I thought of the legal aid attorney, Agent Lopez, Grandpa, the supervisor who’d slid me the box of ergonomic cushions without making a big deal out of it.

“Now I’m learning there are people who can help without expecting to own me afterward,” I said.

At work, I shifted from my old position to a role that let me work from home part‑time. My supervisor framed it as “accommodation” and “flexibility.” To me, it felt like someone had moved a boulder I’d been pushing alone.

I joined an online support group for people with chronic pain. It was the first time I’d been in a space where saying, “I had to lie down in the middle of the day” didn’t feel like admitting failure.

One woman in the group, a nurse from Ohio, wrote, Sometimes the only way to keep your boundaries is to let people be wrong about you.

I copied that into my notebook, right under “Things That Belong To Me.”

Months later, I went to visit Grandpa on a Sunday. His small house smelled like coffee and wood polish. The TV was on low in the background, football muted while the commentary scrolled across the bottom.

The faded flag magnet on his fridge held up a grocery list and a photograph I’d never seen before: me, at eight years old, standing in his backyard with a sparkler in my hand, July Fourth fireworks blooming in the sky behind me. My face was lit up, not by pain or effort, but by surprise.

“You kept this?” I asked, touching the corner of the picture.

“Course I did,” he said. “That was the summer you told me you wanted to be ‘somebody who fixes things.’ Remember?”

I didn’t, not until he said it.

“You said you wanted to fix cars, or houses, or laws,” he continued. “Didn’t matter what. You just wanted to be the person who made things right.” He smiled a little. “Seems like you still are. Just in a different way.”

I looked at the photo again—at the girl holding light in her hand, eyes wide, mouth open on a laugh I couldn’t hear.

The spiral notebook was in my bag, as always. I took it out, flipped to the back, and started a new page.

“Things I’m allowed to want,” I wrote.

A life that doesn’t revolve around making other people comfortable.

Support that doesn’t come with a price tag.

Rest.

Then, after a long pause: To feel safe in my own family someday, even if it’s a family I choose, not the one I was born into.

Grandpa poured us both coffee and turned the game back up.

We sat there in his living room—two people who shared blood but, more importantly, shared a commitment to not lying about what that blood had done.

“You know,” he said during a commercial break, “they’re still telling everyone this was your fault. That you could’ve stopped it.”

I blew on my coffee and took a careful sip.

“They can tell whatever story helps them sleep,” I said. “I’m done auditioning for the role of villain in their version.”

He chuckled, then sobered. “If you ever change your mind, about any of it—”

“I know where you live,” I finished for him.

He smiled. “Yeah. You do.”

On the bus ride home, I sat by the window and watched the city slide by. At one stop, a tired‑looking woman climbed aboard carrying a worn canvas bag like mine. She winced as she sat down, one hand pressed to her lower back.

I recognized the expression.

I didn’t know her story. I didn’t know if anyone had stolen from her, or if the world had just never made room for her pain. I only knew that the way she shifted in her seat looked exactly like the way I sometimes shifted in mine.

I reached into my notebook and tore out a page with a list of low‑cost clinics, hotlines, and legal aid resources I’d started collecting—names and numbers I wished I’d had ten years ago. I kept copies folded in the back now, just in case.

When she stood to get off two stops later, I touched her elbow gently.

“Sorry,” I said when she turned, startled. “You don’t know me. I just… I’ve been where you are. If you ever need help, these people actually show up.”

I held out the folded paper.

Suspicion flickered across her face, then softened. She took it.

“Thanks,” she said quietly.

“You don’t owe anyone anything for using those,” I added without thinking.

Her eyes flashed, just for a second, like she recognized something in me too.

After she stepped off, I leaned back in my seat and closed my eyes.

The bus rumbled forward, carrying me past my parents’ exit, past the turnoff to the neighborhood where the flag magnet still clung to a stainless‑steel fridge in a kitchen paid for with money that should’ve kept my lights on.

I didn’t look back.

Page by page. Dollar by dollar. Boundary by boundary.

I wasn’t just writing my story anymore.

I was choosing, every day, not to let anyone else hold the pen.

News

I buried my 8-year-old son alone. Across town, my family toasted with champagne-celebrating the $1.5 million they planned to use for my sister’s “fresh start.” What i did next will haunt them forever.

I Buried My 8-Year-Old Son Alone. Across Town, My Family Toasted with Champagne—Celebrating the $1.5 Million They Planned to Use…

My husband came home laughing after stealing my identity, but he didn’t know i had found his burner phone, tracked his mistress, and prepared a brutal surprise on the kitchen table that would wipe that smile off his face and destroy his life…

My Husband Came Home Laughing After Using My Name—But He Didn’t Know What I’d Laid Out On The Kitchen Table…

“Why did you come to Christmas?” my mom said. “Your nine-month-old baby makes people uncomfortable.” My dad smirked… and that was the moment I stopped paying for their comfort.

The knocking started while Frank Sinatra was still crooning from the little speaker on my counter, soft and steady like…

I Bought My Nephew a Brand-New Truck… And He Toasted Me Like a Punchline

The phone started buzzing before the sky had fully decided what color it wanted to be. It skittered across my…

“Foreclosure Auction,” Marcus Said—Then the County Assessor Made a Phone Call That Turned Them Ghost-White.

The first thing I noticed was my refrigerator humming too loud, like it knew a storm had just walked into…

SHE RUINED MY SON’S BIRTHDAY GIFTS—AND MY DAD’S WEDDING RING HIT THE TABLE LIKE A VERDICT

The cabin smelled like cedar and dish soap, like someone had tried to scrub summer off the counters and failed….

End of content

No more pages to load